Since 1977, Jon Michael Probstein has assisted people and businesses in all matters. In accordance with the Rules of Professional Conduct, this may be deemed "Attorney Advertising". Nothing contained herein should be construed as legal advice. Admitted in New York and Massachusetts. Always consult a lawyer regarding any matter. Call 888 795-4555 or 212 972-3250 or 516 690-9780. Fax 212 202-6495. Email jmp@jmpattorney.com

Wednesday, November 30, 2016

WHAT IS BAD FAITH IN FORECLOSURE SETTLEMENT CONFERENCES

M&T BANK v. ARCATE, 2016 NY Slip Op 32201 - NY: Supreme Court 2016:

"CPLR 3408 mandates that the court hold a settlement conference in a residential foreclosure action. The statute requires that the parties to a foreclosure action must "negotiate in good faith to reach a mutually agreeable resolution including a loan modification, if possible." A determination of whether a party breached the duty to negotiate in good faith must be based on the totality of the circumstances taking into account that CPLR 3408 is a remedial statute (Citibank, N.A. v. Barclay, 124 AD3d 174, 176, 999 NYS2d 375, 377 (1st Dept., 2014); U.S. Bank, N.A. v. Sarmiento, 121 AD3d 187, 991 NYS2d 68 (2nd Dept., 2014)). The test for determining whether a party participated in good faith in the CPLR 3408 process is clearly one of reasonableness taking into considerations the actions taken by the parties engaging in the settlement conference.

.......

With respect to the issue of "bad faith" there is insufficient proof that the bank acted in "bad faith" during the negotiating process at the mandatory court settlement conferences. Court records indicate that settlement conferences were conducted on August 1, 2013; September 19, 2013; November 25, 2013, December 9, 2013 and March 7, 2014 when the action was marked "not settled". There is no indication that the court attorneys/referees responsible for conducting the conferences considered the conduct of either party as acting in bad faith. While there is evidence of confusion between the parties concerning the amounts due under proposed modification plans offered during the course of negotiations, the record does not show that the bank representatives acted in "bad faith" during negotiations, or for the reason that the bank was unwilling to consent to the terms the defendant claimed she could afford. Under these circumstances no valid basis exists sufficient to warrant imposition of sanctions, or to reschedule additional settlement conferences as the defendant was afforded multiple opportunities to modify the loan which were not acceptable to her."

Tuesday, November 29, 2016

FAMILY LAW - MENTAL ILLNESS AND REMOVAL OF CHILD

MATTER OF GAVIN S., 2016 NY Slip Op 51234 - NY: Family Court 2016:

"FCA §1027 provides that if, after a hearing, "the court finds that removal is necessary to avoid imminent risk to the child's life or health, it shall remove or continue the removal of the child." FCA § 1028, provides that, upon the application of a parent for the return of his or her child who has been removed from his or her care, and following a hearing, "the court shall grant the application unless it finds that the return presents an imminent risk to the child's life or health." In either case, the court must determine if the child's "life or health" would be at "imminent risk" of harm in the respondent's custody and, additionally, whether remaining in or returning to the home would be contrary to the child's best interests (FCA§1027(a)(I); FCA§1028(b); Nicholson v. Scoppetta, 3 NY3d 357, 377 [2004]).

"In order to justify a finding of imminent risk to life or health ... an agency need not prove that the child has suffered actual injury. Rather, a court engages in a fact-intensive inquiry to determine whether the child's [physical or] emotional health is at risk" (Nicholson, 3 NY3d at 377). In reaching its determination, the "court must weigh, in the factual setting before it, whether the imminent risk to the child can be mitigated by reasonable efforts to avoid removal; [i]t must balance [the risk to the child's life or health] against the harm removal might bring; and it must determine factually which course is in the child's best interests" (id. at 378); see also Matter of DeAndre S. (Latoya F. S.), 92 AD3d 888 [2d Dept. 2012]). The language and legislative history of the statute establish that "a blanket presumption favoring removal was never intended" (Nicholson, 3 NY3d at 378; see also Matter of Jesse J. v. Joann K., 64 AD3d 598, 599 [2d Dept 2009]). The Legislature placed "increased emphasis on preventive services designed to maintain family relationships rather than responding to children and families in trouble only by removing the child from the family" (Mark G. v Sabol, 93 NY2d 710, 719 [1999]; see also Nicholson, 3 NY3d at 374).

A mental illness that causes a parent to act in a way that presents an imminent risk to his or her child's life or health may support a removal of the child from the parent's care under FCA §1027, just as a finding of neglect under FCA §1012 may be predicated "upon proof that a child's physical, mental, or emotional condition was impaired or was placed in imminent danger of becoming impaired as a result of a parent's mental illness" (see, e.g., Matter of Soma H., 306 AD2d 531[ 2d Dept 2003]). However, just as "proof of mental illness alone will not support a finding of neglect" (Matter of Joseph A. [Fausat O.], 91 AD3d 638, 640, [2d Dept 2012]), neither will it support a removal of the child from the parent's care in the absence of evidence that the parent's illness creates an imminent risk to the child's life or health. As the Court of Appeals cautioned in Nicholson, "[t]he plain language of [FCA§1027] and the legislative history supporting it establish that a blanket presumption favoring removal was never intended. The court must do more than identify the existence of a risk of serious harm." (3 NY3d at 378 [emphasis in original]). There must be proof of an identifiable, specific, serious and imminent risk to the life or health of the child (see Nicholson, 3 NY3d at 377 [the court must engage "in a fact-intensive inquiry" to determine whether the child's life or health is at risk]) caused by the parent's mental illness. In determining whether removal is necessary to avoid imminent risk to the child's life or health, the statute also requires the court to consider "whether continuation in the child's home would be contrary to the best interests of the child and where appropriate, whether reasonable efforts were made ... to prevent or eliminate the need for removal...." (FCA§1027(b)(ii)). In sum, if the court determines that an imminent risk to the child's life or health exists, it "must weigh, in the factual setting before it, whether the ... risk to the child can be mitigated by reasonable efforts to avoid removal, ... balance that risk against the harm removal might bring, and ... determine factually which course is in the child's best interests" (Nicholson, 3 NY3d at 378; see also Matter of Baby Boy D. (Adanna C.), 127 AD3d 1079 [2d Dept. 2015]).The Court in Nicholson also stressed that "imminent" means "near or impending, not merely possible" (3 NY3d at 369; see also Baby Boy D., 127 AD3d at 1080 ("imminent" risk must be shown to justify removal).

......

As previously noted, a parent's mental illness, standing alone, is not a basis for a neglect finding (Matter of Joseph A., supra, 91 AD3d at 640). A fortiori, it does not justify removal of a child from his parent's care in the absence of evidence that the child's life or health is in imminent risk of harm as a result of that illness (cf. Nicholson, 3 NY3d at 375 (exposure of a child to domestic violence is not presumptively neglectful, so "a fortiori, [it] is not presumptively ground for removal, and in many instances removal may do more harm to the child than good"). Where no such imminent risk has been shown, a removed child must be returned to the parent (see, e.g., In the Matter of Jeremiah L., 45 AD3d 771 [2d Dept. 2007]; FCA§1028(a) ("court shall grant the application [for return of a child], unless it finds that the return presents an imminent risk to the child's life or health") [emphasis added]). ACS's speculative concern that Ms. S might have be hospitalized again for her mental illness cannot serve as a basis for a finding of "imminent risk" (see Baby Boy D., 127 AD3d at 1080 [speculation that the mother might not enforce an order of protection against the father could not support a finding of imminent risk to the child's life or health]), particularly when she has been consistent with all aspects of her mental health treatment and has cooperated with the services that were put in place for her and Gavin.

As ACS failed to establish that Gavin's life or health were ever placed in imminent risk as a result of Ms. S's mental illness, ACS's application under FCA§1027 must be denied, and Gavin must be returned to his mother....."

Monday, November 28, 2016

DIVORCE - VACATING A DEFAULT

This can arise in various situations in a matrimonial matter e.g. failure to file an answer or a motion. The policy of the courts has been recently set forth in FLORESTAL v. COLEMAN-FLORESTAL, 2016 NY Slip Op 5789 - NY: Appellate Div., 2nd Dept. 2016:

" "While a party attempting to vacate a default must establish both a reasonable excuse for the default and a potentially meritorious cause of action, defense, or opposition to a motion, this Court has adopted a liberal policy with respect to vacating defaults in matrimonial matters because the State's interest in the marital res and related issues favors dispositions on the merits" (Backhaus v Backhaus, 128 AD3d 872, 872-873; see Alam v Alam, 123 AD3d 1066, 1067)."

Wednesday, November 23, 2016

HAPPY THANKSGIVING

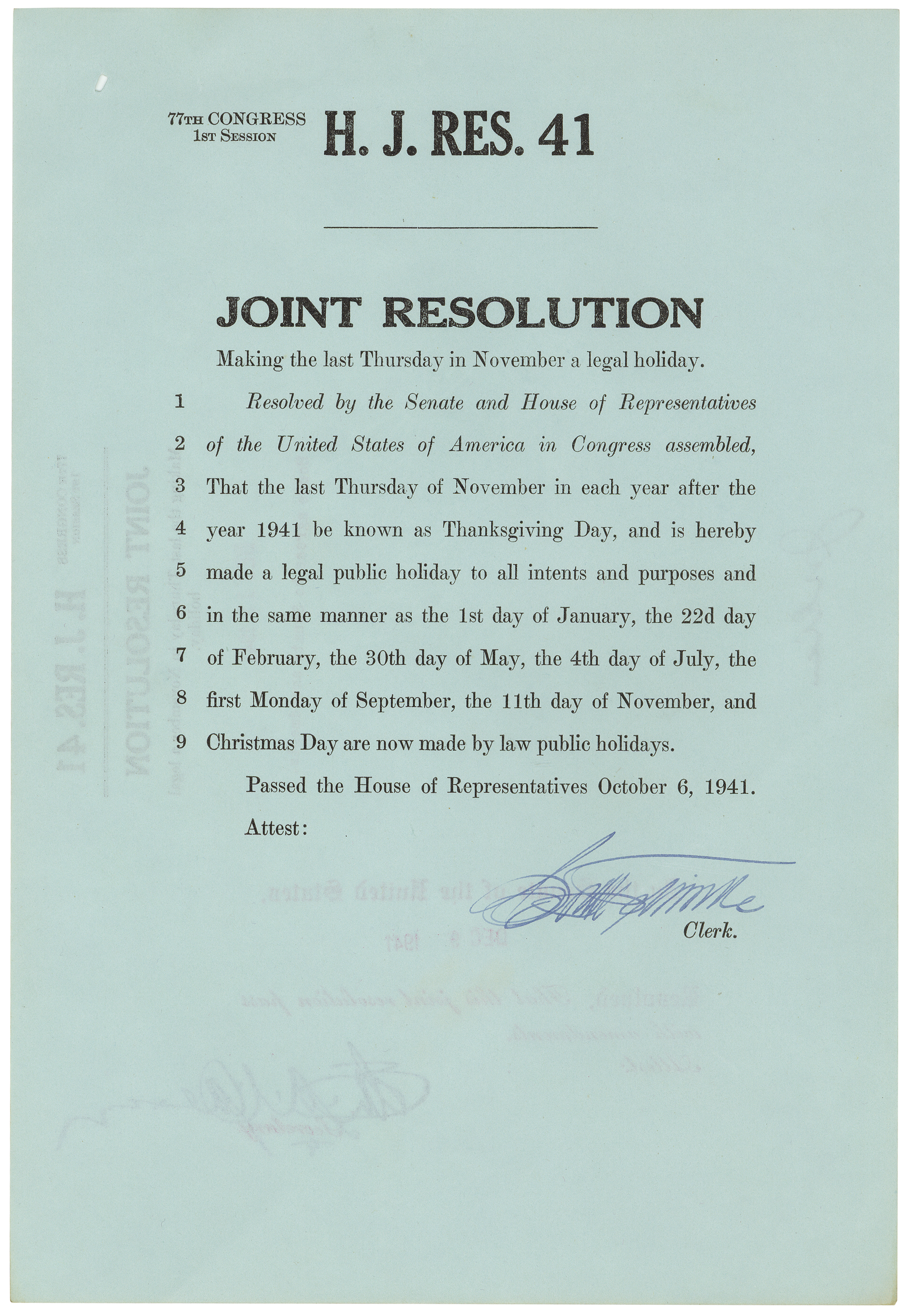

From the National Archives:

"On September 28, 1789, just before leaving for recess, the first Federal Congress passed a resolution asking that the President of the United States recommend to the nation a day of thanksgiving. A few days later, President George Washington issued a proclamation naming Thursday, November 26, 1789 as a "Day of Publick Thanksgivin" - the first time Thanksgiving was celebrated under the new Constitution. Subsequent presidents issued Thanksgiving Proclamations, but the dates and even months of the celebrations varied. It wasn't until President Abraham Lincoln's 1863 Proclamation that Thanksgiving was regularly commemorated each year on the last Thursday of November.

In 1939, however, the last Thursday in November fell on the last day of the month. Concerned that the shortened Christmas shopping season might dampen the economic recovery, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued a Presidential Proclamation moving Thanksgiving to the second to last Thursday of November. As a result of the proclamation, 32 states issued similar proclamations while 16 states refused to accept the change and proclaimed Thanksgiving to be the last Thursday in November. For two years two days were celebrated as Thanksgiving - the President and part of the nation celebrated it on the second to last Thursday in November, while the rest of the country celebrated it the following week.

To end the confusion, Congress decided to set a fixed-date for the holiday. On October 6, 1941, the House passed a joint resolution declaring the last Thursday in November to be the legal Thanksgiving Day. The Senate, however, amended the resolution establishing the holiday as the fourth Thursday, which would take into account those years when November has five Thursdays. The House agreed to the amendment, and President Roosevelt signed the resolution on December 26, 1941, thus establishing the fourth Thursday in November as the Federal Thanksgiving Day holiday."

Tuesday, November 22, 2016

COLLECTING RENT ON AN ILLEGAL APARTMENT

LISPENARD STUDIO CORP. v. Loeb, 2016 NY Slip Op 30945 - NY: City Court, Civil Court 2016:

"A substantial body of law supports the proposition that MDL §302 rent forfeiture provisions do not apply if the tenant was complicit in the existence and maintenance of an illegal apartment, Zane v. Kellner, 240 A.D.2d 208, 209 (1st Dept. 1997), 58 E. 130th St. LLC v. Mouton, 25 Misc. 3d 509, 511 (Civ. Ct. N.Y. Co. 2009), citing, Zafra v. Sawchuk, N.Y.L.J., Jan. 9, 1995, at 27:2 (App. Term 1st Dept), if the tenants knew that their occupancy was illegal, Zane, supra, 240 A.D.2d at 209, Eli Haddad Corp. v. Cal Redmond Studio, 102 A.D.2d 730 (1st Dept. 1984), Lipkis v. Pikus, 99 Misc.2d 518, 520 (App. Term 1st Dept. 1979), aff'd, 72 A.D.2d 697 (1st Dept 1979), appeal dismissed, 51 N.Y.2d 874 (1980), Dodds v. 1926 Third Ave. Realty Corp., 2011 N.Y. Misc. LEXIS 3921 (S. Ct. N.Y. Co. 2011), if the tenants somehow prevented the legalization, Chatsworth 72nd Street Corp. v. Rigai, 71 Misc. 2d 647, 651 (Civ. Ct. N.Y. Co. 1972), aff'd, 74 Misc.2d 298 (App. Term 1st Dept.), aff'd, 43 A.D.2d 685 (1st Dept. 1973), aff'd on the opinion of the Civil Court of the City of New York, 35 N.Y.2d 984, 895 (1975), First Edition Composite, Inc. v. Wilkson, 177 A.D.2d 297, 299 (1st Dept. 1991), Hornfeld v. Gaare, 130 A.D.2d 398, 400 (1st Dept. 1987), Amdar v. Armenti, N.Y.L.J. June 23, 1994 at 28:4 (App. Term 1st Dept.), or if the subject premises do not pose a threat to the tenant's health and safety. Zane, supra, 240 A.D.2d at 209, Dogwood Residential, LLC v. Stable 49, Ltd., 2016 N.Y. Misc. LEXIS 1362 (S. Ct. N.Y. Co. 2016), citing Beneficial Cap. Corp. v. Richardson, No. 92 Civ. 3785, 1995 US Dist LEXIS 7354 (S.D.N.Y. 1995).

This authority relies upon an "abandon[ment of] a literal application of MDL §302 in favor of allowing equity to control in order to avoid a tenant's unjust enrichment," as one Court put it. B.S.L. One Owners Corp. v. Rubenstein, 159 Misc.2d 903, 908 (Civ. Ct. Richmond Co. 1994). However, a recent Court of Appeals case rejects the abandonment of a literal application of MDL §302. Chazon, LLC v. Maugenest, 19 N.Y.3d 410, 415-16 (2012)("[i]n the absence of compliance, the law's command is quite clear . . . [judicially-carved-out exceptions to MDL §302] may make sense from a practical point of view. But we find nothing . . . to explain how they can be reconciled with the text of the statute. They simply cannot. . . . If that is an undesirable result, the problem is one to be addressed by the Legislature"). The Court's strict application of MDL §302 appears to render the rest of the authority standing for a different result without effect. Accord, 742 Realty LLC v. Zimmer, 46 Misc.3d 1204(A) (Civ. Ct. N.Y. Co. 2014), citing Caldwell v. American Package Company, Inc., 57 AD3d 15, 26, 866 N.Y.S.2d 275 (2nd Dept. 2008).

Petitioner argues that Phillips & Huyler Assocs. v. Flynn, 225 A.D.2d 475 (1st Dept. 1996) compels a different result, insofar as it holds that application of MDL §302 could unjustly enrich a tenant. However, not only does this ruling pre-date Chazon, LLC, supra, 19 N.Y.3d at 410, not only does this ruling come from a Court lower than the Court in Chazon, LLC, supra, 19 N.Y.3d at 410, but this ruling favors the position of a commercial landlord, not a residential landlord. MDL §302 evinces a limited application to residential tenants. 455 Second Ave. LLC v. NY Sch. of Dog Grooming, Inc., 37 Misc.3d 933, 936 (Civ. Ct. N.Y. Co. 2012).

Another argument against application of MDL §302 to this proceeding is that the parties have contracted that Respondents were the parties responsible for legalizing their occupancy of the subject premises. Contracts between cooperatives and shareholders valid, Kenneth D. Laub & Co. v. Bear Stearns Cos., 262 A.D.2d 36 (1st Dept. 1999), and indeed, include elements of self-determination not found in leases for apartments in privately-owned buildings, as shareholders devise by policy themselves through a board of directors elected by them. 930 Fifth Corp. v. King, 71 Misc.2d 359, 364 (App. Term 1st 1972).[3] However, the default proposition is that a cooperative, rather than an individual shareholder, bears responsibility for obtaining a residential certificate of occupancy. O'Flaherty v. Schwimmer, 158 Misc.2d 420, 424-425 (S. Ct. N.Y. Co. 1993)(Tom, J.), unanimously affirmed for the reasons stated, 208 A.D.2d 425 (1st Dept. 1994). The proposition that the parties can shift this responsibility rests upon the premise that a tenant's rights as defined by MDL §302 are waivable when, in fact, authority holds that they are not waivable. Dawkins v. Ruff, 10 Misc.3d 88, 89 (App. Term 2nd Dept. 2005), BFN Realty Assocs. v. Cora, 8 Misc.3d 139(A) (App. Term 2nd Dept. 2005), Willoughby Assocs. v. Dance-Lonesome, 2003 N.Y. Misc. LEXIS 822 (App. Term 2nd Dept. 2003).

Petitioner argues that Respondents' hands are "unclean" such as to preclude the relief Respondents seek, relief that Petitioner characterizes as equitable. Petitioner's reasoning is backwards. It is Petitioner that is seeking an equitable relief from the dictates of MDL §302. See B.S.L. One Owners Corp., supra, 159 Misc.2d at 903. The Court of Appeals rejected an "equitable" approach to MDL §302 insofar as it found the statute inconsistent with concerns of unjust enrichment. Chazon, LLC, supra, 19 N.Y.3d at 416.

Chazon, LLC, supra, 19 N.Y.3d at 410, applies MDL §302 to a landlord who has not complied with the legalization schedules set pursuant to MDL §281 et seq., commonly known as the Loft Law. A broad remedial purpose of the Loft Law was to confer rent-stabilized status on legalized interim multiple dwellings. Tan Holding Corp. v. Wallace, 187 Misc.2d 687, 688 (App. Term 1st Dept. 2001), Walsh v. Salva Realty Corp., 2009 N.Y. Misc. LEXIS 6056, 7-8 (S. Ct. N.Y. Co. 2009). As cooperatives cannot be subject to the Rent Stabilization Law, 9 N.Y.C.R.R. §2520.11(1), Loft Law coverage does not apply to owner-occupied cooperatives such as the subject premises, Tri-Land Properties, Inc. v. 115 West 28th St. Corp., 267 A.D.2d 142 (1st Dept. 1999), raising a question about the factual distinction between this matter and the facts of Chazon, LLC, supra, 19 N.Y.3d at 410. However, the Court in Chazon, LLC, supra, 19 N.Y.3d at 410 interpreted MDL §302 on its plain language, employing a canon of interpretation that does not depend on the particular facts of the case. Nothing in the text of MDL §302 restricts such an interpretation solely to a landlord of a property subject to the Loft Law and, indeed, MDL §302 pre-dates the Loft Law."

Monday, November 21, 2016

IS CUSTODY SHARED OR NOT

MATTER OF MITCHELL v. Mitchell, 134 AD 3d 1213 - NY: Appellate Div., 3rd Dept. 2015:

"Initially, we reject the father's argument that Family Court should have determined that he was the child's custodial parent. Generally, the custodial parent for purposes of child support is the parent who has physical custody of a child for the majority of the time "based upon the reality of the situation" (Riemersma v Riemersma, 84 AD3d 1474, 1476 [2011] [internal quotation marks and citation omitted]). If the parenting time is shared equally, then the parent with greater income is deemed to be the noncustodial parent for purposes of calculating child support (see Smith v Smith, 97 AD3d 923, 924 [2012]).

Here, no party disputes the Support Magistrate's conclusion that, during the school year, the child spends an equal number of overnights at each party's home and, during the summer months, the child is with the mother eight nights and the father six nights. Consequently, Family Court determined that because the parents' have "close to equally shared physical custody," the father, as the more monied spouse, was the noncustodial parent. The father contends that he has physical custody of the child a majority of the time because, pursuant to the 2007 order, the child was with him eight full days, six nights and two half days during any 14-day period in the summer months, and, therefore, he should be deemed the custodial parent.[1] The flaw in this argument is that "shared" custody need not be "equal" (Smith v Smith, 97 AD3d at 924). Here, with the exception of the days during the summer weeks when the mother was unavailable and the father was available to exercise parenting time, the custodial schedule was unchanged, and we decline to accord greater weight to the custodial days as compared to the overnight custodial periods (see Matter of Somerville v Somerville, 5 AD3d 878, 880 [2004]). Based on the "reality of the situation" (Riemersma v Riemersma, 84 AD3d at 1476 [internal quotation marks and citation omitted]), as demonstrated by the record, we discern no error in Family Court's determination that the parties shared "close to equally shared physical custody of the child.""

Friday, November 18, 2016

IS CUSTODY SHARED OR NOT

MATTER OF TM v. JK, 2016 NY Slip Op 26315 - NY: Family Court 2016:

"......Respondent's basic visitation schedule consisted of three weekends per month, one night during the week (as agreed), and holidays and vacations (as agreed). For the 2015 calendar year, the evidence (particularly, respondent's exhibit A) showed that the child spent about 33.74 percent of all hours with the father, and thus the child spent about 66.26 percent of all hours with the mother. Respondent's exhibit A also showed that the child spent "40.27 % of all days" with the father, but this percentage is skewed because some of the "days" were not overnights. Courts have declined to accord greater weight to the custodial days as compared to the overnight custodial periods (see, Somerville, id. at 880, and Matter of Mitchell v. Mitchell, 134 AD3d 1213, 1215 [3d Dept 2015]). Clearly, the petitioner is the party with primary physical residence of the child."

Thursday, November 17, 2016

MODIFICATION OF CUSTODY WHEN SIBLINGS ARE INVOLVED

In Cook v. Cook, 2016 NY Slip Op 5743 - NY: Appellate Div., 2nd Dept. 2016, the children were around 12 and 9 at the time of the hearing:

"A party seeking the modification of an existing court-ordered child custody arrangement has the burden of demonstrating that circumstances have changed since the initial custody determination" such that modification is necessary to ensure the children's best interests (Musachio v Musachio, 137 AD3d 881, 882-883; see Matter of Klotz v O'Connor, 124 AD3d 662, 662-663). "In determining whether a custody agreement that was incorporated into a judgment of divorce should be modified, the paramount issue before the court is whether, under the totality of the circumstances, a modification of custody is in the best interests of the [children]" (Matter of Honeywell v Honeywell, 39 AD3d 857, 858; see Anonymous 2011-1 v Anonymous 2011-2, 102 AD3d 640, 641). To determine whether modification of a custody arrangement is in the best interests of the children, the court must weigh several factors of varying degrees of importance, including, inter alia, (1) the original placement of the children, (2) the length of that placement, (3) the children's desires, (4) the relative fitness of the parents, (5) the quality of the home environment, (6) the parental guidance given to the children, (7) the parents' relative financial status, (8) the parents' relative ability to provide for the children's emotional and intellectual development, and (9) the willingness of each parent to assure meaningful contact between the children and the other parent (see Anonymous 2011-1 v Anonymous 2011-2, 136 AD3d 946, 948; Cuccurullo v Cuccurullo, 21 AD3d 983, 984).

Here, the father demonstrated a sufficient change in circumstances to warrant modification of the custody provisions of the settlement agreement so as to award him residential custody of Jonathan. The record supports the Supreme Court's determination that Jonathan's relationship with the mother has deteriorated since the prior custody arrangement was agreed to (see Matter of Burke v Cogan, 122 AD3d 625, 626; Matter of Filippelli v Chant, 40 AD3d 1221, 1222; Matter of Maute v Maute, 228 AD2d 444), and that the father exhibits a greater sensitivity to his emotional and psychological needs, particularly with respect to the environment in Jonathan's new school (see Matter of Dorsa v Dorsa, 90 AD3d 1046, 1047). We discern no reason to disturb the court's determination that the father's testimony was more credible than the mother's testimony. Additionally, the attorney for the children advocated for residential custody to be awarded to the father, since Jonathan, who was 12 years old when the father's petition was filed, communicated a preference to reside with him. While the express wishes of a child are not controlling (see Matter of Ross v Ross, 86 AD3d 615; Matter of Bond v MacLeod, 83 AD3d 1304), the child's wishes should be considered and are entitled to great weight, where, as here, the child's age and maturity would make his input particularly meaningful (see Matter of Coull v Rottman, 131 AD3d 964; Matter of Rosenblatt v Rosenblatt, 129 AD3d 1091; Koppenhoefer v Koppenhoefer, 159 AD2d 113). Accordingly, the court's determination to modify the custody provisions of the settlement agreement so as to award the father residential custody of Jonathan has a sound and substantial basis in the record.

However, the Supreme Court's determination that the evidence did not demonstrate a sufficient change in circumstances warranting modification of the custody provisions of the settlement agreement so as to award the father residential custody of the parties' child Madison is not supported by a sound and substantial basis in the record. It "has long [been] recognized that it is often in the child's best interests to continue to live with his [or her] siblings" (Eschbach v Eschbach, 56 NY2d 167, 173), and "the courts will not disrupt sibling relationships unless there is an overwhelming need to do so" (Matter of Lao v Gonzales, 130 AD3d 624, 625; see Matter of Shannon J. v Aaron P., 111 AD3d 829, 831). It is undisputed that Jonathan and Madison have a close relationship, and, based upon the recommendations of the children's therapist that they should not be separated, the position of the attorney for the children that they should remain with the same custodial parent, and evidence that the father demonstrated more of an ability and willingness to assure meaningful contact between the children and the mother, and to foster a healthier relationship between the children and the mother, than the mother would have fostered between the children and the father, the court should have awarded residential custody of Madison to the father (see Eschbach v Eschbach, 56 NY2d at 173-174; Matter of Shannon J. v Aaron P., 111 AD3d at 831; Matter of Pappas v Kells, 77 AD3d 952; Matter of Tori v Tori, 67 AD3d 1021)."

Wednesday, November 16, 2016

PLEASE EXCUSE MAIL DELAY

Server issues exist for next two day but I can also be reached at jmpattorney@gmail.com

Tuesday, November 15, 2016

THE ELEMENTS OF CIVIL CONTEMPT

Dotzler v. Buono, 2016 NY Slip Op 7433 - NY: Appellate Div., 4th Dept. 2016:

"A finding of civil contempt must be supported by four elements: (1) "a lawful order of the court, clearly expressing an unequivocal mandate, was in effect"; (2) "[i]t must appear, with reasonable certainty, that the order has been disobeyed"; (3) "the party to be held in contempt must have had knowledge of the court's order, although it is not necessary that the order actually have been served upon the party"; and (4) "prejudice to the right of a party to the litigation must be demonstrated" (Matter of McCormick v Axelrod, 59 NY2d 574, 583, order amended 60 NY2d 652). The party seeking an order of contempt has the burden of establishing those four elements by clear and convincing evidence (see El-Dehdan v El-Dehdan, 26 NY3d 19, 29; Belkhir v Amrane-Belkhir, 128 AD3d 1382, 1382).

Here, we agree with defendant that plaintiff failed to establish by the requisite clear and convincing evidence that defendant had actual knowledge of the TRO at the time ........ (see Puro v Puro, 39 AD2d 873, 873, affd 33 NY2d 805). We reject plaintiff's contention that defendant's actual knowledge of the TRO is not necessary here because she served the TRO upon defendant's attorney (see CPLR 2103 [b]). "Actual knowledge of a judgment or order is an indispensable element of a contempt proceeding" (Orchard Park Cent. Sch. Dist. v Orchard Park Teachers Assn., 50 AD2d 462, 468, appeal dismissed 38 NY2d 911; see Matter of Howell v Lovell, 103 AD3d 1229, 1230), and the record establishes that defendant did not receive the TRO before ........"

Monday, November 14, 2016

ADOPTED CHILD (UNDER 21) CAN SUE ADOPTIVE PARENT FOR CHILD SUPPORT

A few years back, news was made when a Lincoln Park, N.J, high school student filed a lawsuit against her parents seeking living expenses and tuition for private high school and college.

In MATTER OF SUPPORT PROCEEDING JM v. RM, 2016 NY Slip Op 51136 - NY: Family Court 2016, the 20 year old Petitioner filed for support against Respondent, his adoptive mother:

"Pursuant to DRL § 110 and DRL § 117(1)(a), adoptive parents are liable for support of their adopted children and the natural parents are relieved of all responsibility for support. See also, Harvey-Cook v. Neill, 118 AD2d 109, 504 N.Y.S.2d 434 (2d Dep't 1986). The Family Court Act sets forth the "fundamental public policy in New York" that parents of minor children are responsible for their children's support until age twenty-one. See, FCA §413 (1) (a). In the instant case, Petitioner is the adoptive son and Respondent is the adoptive mother. Respondent, as the adoptive mother, is legally responsible to support Petitioner until he turns twenty-one years old."

Thursday, November 10, 2016

Wednesday, November 9, 2016

BASIC STANDARDS IN CHILD CUSTODY

MATTER OF SCHULTHEIS v. Schultheis, 2016 NY Slip Op 5648 - NY: Appellate Div., 2nd Dept. 2016:

"The parties were married in 1996 and have two children. The family lived together until December 2014, when the mother left the marital residence and petitioned the Family Court for sole residential custody of the children. After a hearing, the Family Court awarded residential custody to the mother with liberal visitation to the father. The father appeals.

There is "no prima facie right to the custody of the child in either parent" (Domestic Relations Law §§ 70[a]; 240[1][a]; see Friederwitzer v Friederwitzer, 55 NY2d 89, 93; Matter of Riccio v Riccio, 21 AD3d 1107). The essential consideration in making an award of custody is the best interests of the children (see Eschbach v Eschbach, 56 NY2d 167, 171; Friederwitzer v Friederwitzer, 55 NY2d 89; Matter of McIver-Heyward v Heyward, 25 AD3d 556), which are determined by a review of the totality of the circumstances (see Matter of Garcia v Fountain, 82 AD3d 979, 980). In making a determination as to what custody arrangement is in the children's best interests, the court should consider the quality of the home environment and the parental guidance the custodial parent provides for the children, the ability of each parent to provide for the children's emotional and intellectual development, the financial status and ability of each parent to provide for the children, the relative fitness of the respective parents, and the effect an award of custody to one parent might have on the children's relationship with the other parent (see Matter of Hutchinson v Johnson, 134 AD3d 1115, 1116; Mohen v Mohen, 53 AD3d 471, 472-473; Miller v Pipia, 297 AD2d 362, 364 ). The court should also consider the children's wishes, weighed in light of their ages and maturity (see Eschbach v Eschbach, 56 NY2d at 173; Matter of Langlaise v Sookhan, 48 AD3d 685, 686). "As a custody determination depends to a great extent upon an assessment of the character and credibility of the parties and witnesses, the findings of the Family Court will not be disturbed unless they lack a sound and substantial basis in the record" (Matter of Tercjak v Tercjak, 49 AD3d 772, 772; see Matter of Gilmartin v Abbas, 60 AD3d 1058).

We see no reason to disturb the Family Court's well-reasoned determination to award residential custody to the mother. The record shows that both parents love the subject children, but that the father is unable to provide for the children's well-being and promote their relationship with the mother. Accordingly, the Family Court's determination is supported by a sound and substantial basis in the record.

Tuesday, November 8, 2016

Monday, November 7, 2016

Friday, November 4, 2016

CPLR 321 (C) AUTOMATIC STAY

CPLR 321 (c): provides:

"Death, removal or disability of attorney. If an attorney dies, becomes physically or mentally incapacitated, or is removed, suspended or otherwise becomes disabled at any time before judgment, no further proceeding shall be taken in the action against the party for whom he appeared, without leave of the court, until thirty days after notice to appoint another attorney has been served upon that party either personally or in such manner as the court directs."

The stay is automatic. Most recently in DUANDRE CORP. v. GOLDEN KRUST CARIBBEAN BAKERY & GRILL, 2016 NY Slip Op 4461 - NY: Appellate Div., 1st Dept. 2016:

"The suspension of defendant's counsel during the pendency of this action resulted in an automatic stay of the proceedings against defendant until thirty days after notice to appoint another attorney was served upon him, or until the court granted leave to resume proceedings (CPLR 321[c]; Moray v Koven & Krause, Esqs., 15 NY3d 384, 388-390 [2010]). Because there was no compliance with the leave or notice requirements of CPLR 321(c), and the record demonstrates that defendant did not retain new counsel until February 2014, the automatic stay was in place when the November 22, 2013 judgment was entered based upon defendant's default. Accordingly, the judgment must be vacated. Defendant's failure to invoke CPLR 321(c) until submission of his reply papers on his motion does not result in a waiver of his argument (Moray, 15 NY3d at 390). Nor was he required to submit an affidavit of merit (Scirica v Colantonio, 111 AD3d 571, 572 [1st Dept 2013])."

Thursday, November 3, 2016

THE "NO SELFIE" ELECTION LAW

The law is statutory and can be found in the New York Election Law:

"ARTICLE 17 VIOLATIONS OF THE ELECTIVE FRANCHISE

Sec. 17-130. Misdemeanor in relation to elections Any person who:

.....

10. Shows his ballot after it is prepared for voting, to any person so as to reveal the contents, or solicits a voter to show the same; or,

....."

A strict reading of the statute reveals that you can take a "selfie" of your ballot but you can't show it to any one.

Wednesday, November 2, 2016

FAILURE TO PAY CHILD SUPPORT - INCARCERATION

MATTER OF STRADFORD v. Blake, 2016 NY Slip Op 5651 - NY: Appellate Div., 2nd Dept. 2016:

The mother commenced this proceeding against the father, alleging that he was in willful violation of a child support order dated June 30, 2006. Following a hearing, the Support Magistrate found that the father was in willful violation of the order of support and issued an order of disposition recommending that the court consider a period of incarceration. The Family Court, in effect, confirmed the Support Magistrate's findings of fact, granted the mother's petition, and issued an order of commitment, committing the father to the custody of the Nassau County Correctional Facility for a period of six months unless he paid the purge amount of $112,342.80. The father appeals.

Although the appeal from so much of the order of commitment as directed that the father be incarcerated must be dismissed as academic, the appeal from so much of the order of commitment as confirmed the finding and determination that the father was in willful violation of the order of support is not academic in light of the enduring consequences which could flow from the finding that he violated the order of support (see Matter of Dezil v Garlick, 136 AD3d 904; Matter of Rodriguez v Suarez, 93 AD3d 730; Matter of Westchester County Commr. of Social Servs. v Perez, 71 AD3d 906, 907).

Under Family Court Act § 454(3)(a), which relates to "willful" failures to obey support orders, a "`failure to pay support as ordered itself constitutes prima facie evidence of a willful violation'" (Matter of Dezil v Garlick, 136 AD3d at 905, quoting Matter of Powers v Powers, 86 NY2d 63, 69; see Family Ct Act § 454[3][a]). This means that "`proof that respondent has failed to pay support as ordered alone establishes petitioner's direct case of willful violation, shifting to respondent the burden of going forward'" (Matter of Dezil v Garlick, 136 AD3d at 905, quoting Matter of Powers v Powers, 86 NY2d at 69).

Here, the mother presented proof that the father failed to pay child support as ordered (see Matter of Saintime v Saint Surin, 40 AD3d 1103). The burden of going forward then shifted to the father to offer competent, credible evidence of his inability to make the required payments (see Matter of Powers v Powers, 86 NY2d at 69; Matter of Dezil v Garlick, 136 AD3d at 905). The father failed to sustain his burden. The Support Magistrate found the father to be less than credible. Even assuming the truth of the father's contention that he had been unemployed in his chosen field since he lost his license to trade stocks and that he could not perform physical labor due to his heart condition, he failed to present any evidence that he had made a reasonable and diligent effort to secure employment. Thus, the father failed to meet his burden of presenting competent, credible evidence that he was unable to make payments as directed (see Matter of Dezil v Garlick, 136 AD3d at 905; Matter of Nassau County Dept. of Social Servs. v Henry, 136 AD3d 639; Matter of Girasek-Brick v Girasek, 127 AD3d 861; cf. Matter of Westchester County Commr. of Social Servs. v Perez, 71 AD3d 906). Moreover, the father did not regularly pay child support between 2001, when the first order directing that he pay child support was entered, and 2014, when the hearing was held on the mother's petition. The father failed to provide proof that he applied for and was denied Social Security disability benefits even though directed to do so by the Support Magistrate. In addition, the Support Magistrate properly found that the father lacked credibility in his testimony that he had no income or assets from other sources.

Accordingly, the Family Court properly, in effect, confirmed the determination of the Support Magistrate that the father willfully violated the order of support (see Matter of Dezil v Garlick, 136 AD3d at 905).

Tuesday, November 1, 2016

SECTION 8 VOUCHERS, ETC. AND HOUSING DISCRIMINATION

The NYC Human Rights Law prohibits discrimination in housing based on your actual or perceived race, color, creed, age, national origin, alienage or citizenship status, gender (including gender identity and sexual harassment), sexual orientation, disability, marital status, partnership status, lawful occupation, family status, or lawful source of income. Lawful source of income includes income from Social Security, or any form of federal, state, or local public assistance or housing assistance including Section 8 vouchers.

See http://www.nyc.gov/html/fhnyc/html/protection/income.shtml