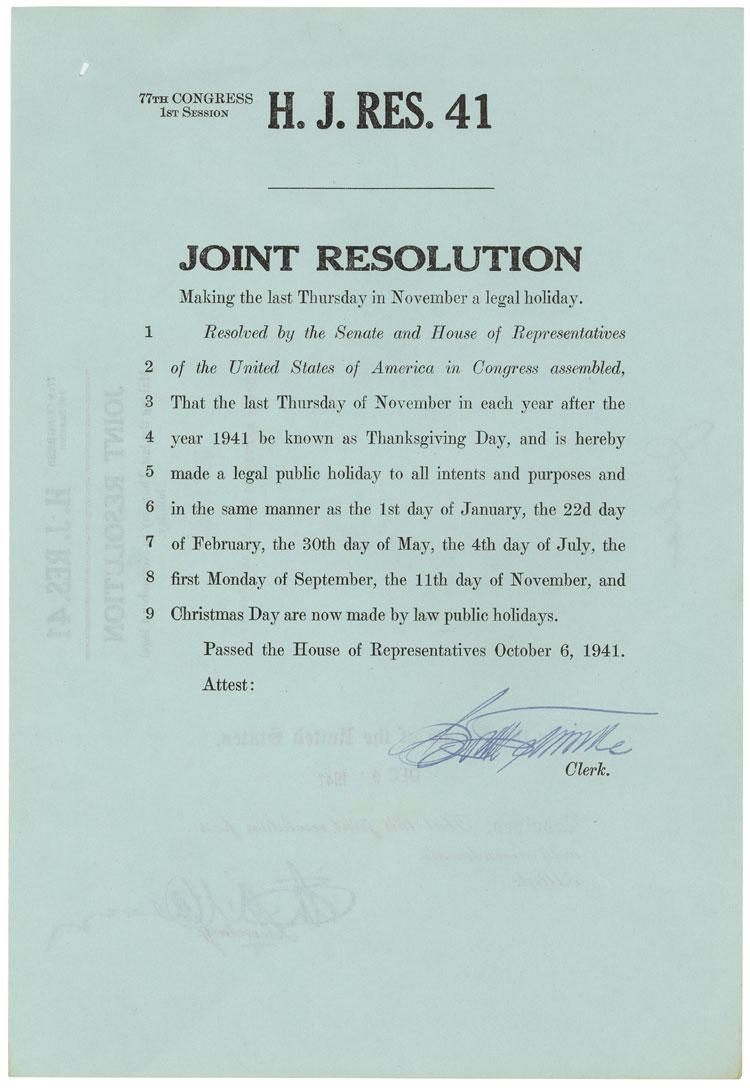

"On October 6, 1941, the House passed a joint resolution declaring the

last Thursday in November to be the legal Thanksgiving Day. The Senate,

however, amended the resolution establishing the holiday as the fourth

Thursday, which would take into account those years when November has

five Thursdays. The House agreed to the amendment, and President

Roosevelt signed the resolution on December 26, 1941, thus establishing

the fourth Thursday in November as the Federal Thanksgiving Day holiday."

Since 1977, Jon Michael Probstein has assisted people and businesses in all matters. In accordance with the Rules of Professional Conduct, this may be deemed "Attorney Advertising". Nothing contained herein should be construed as legal advice. Admitted in New York and Massachusetts. Always consult a lawyer regarding any matter. Call 888 795-4555 or 212 972-3250 or 516 690-9780. Fax 212 202-6495. Email jmp@jmpattorney.com

Wednesday, November 27, 2019

Tuesday, November 26, 2019

YELLOWSTONE, IF NOT WAIVED, STILL LIVES

Although the right to bring a Yellowstone injunction can be waived (159 MP Corp. v Redbridge Bedford, LLC 2019, NY Slip Op 03526, Decided on May 7, 2019 ,Court of Appeals DiFiore, J.), in this case, there was no waiver.

456 Johnson, LLC v Maki Realty Corp., 2019 NY Slip Op 08384, Decided on November 20, 2019, Appellate Division, Second Department:

"In April 2015, the defendant landlord, Maki Realty Corp., entered into a commercial lease with the plaintiff tenant, 456 Johnson, LLC, relating to certain real property located in Brooklyn. On or about April 28, 2016, the defendant served the plaintiff with a "Thirty (30) Day Notice to Cure" (hereinafter notice to cure), alleging several violations of the lease. The defendant demanded that the plaintiff cure all the violations listed in the notice to cure on or before May 31, 2016, and stated that if the violations were not cured by that date, the defendant would elect to terminate the lease.

On May 17, 2016, the plaintiff commenced this action, inter alia, to enjoin the defendant from terminating the lease and for a judgment declaring that it did not breach the terms of the lease as alleged in the notice to cure, and simultaneously moved by order to show cause for [*2]a Yellowstone injunction (see First Natl. Stores v Yellowstone Shopping Ctr., 21 NY2d 630) enjoining the defendant from terminating the lease pending resolution of the action. In an order dated August 5, 2016, the Supreme Court granted the plaintiff's motion for a Yellowstone injunction on the condition that it, inter alia, pay real estate taxes in compliance with the lease.

The defendant then moved for summary judgment dismissing the complaint, and the plaintiff cross-moved for summary judgment, inter alia, on so much of its first cause of action as was for a judgment declaring that it did not breach the lease. The defendant also separately moved, inter alia, to vacate the Yellowstone injunction. The Supreme Court conditionally granted that branch of the defendant's motion which was to vacate the Yellowstone injunction, denied the defendant's motion for summary judgment dismissing the complaint, and granted the subject branch of the plaintiff's cross motion.

"A motion to vacate or modify a preliminary injunction is addressed to the sound discretion of the court and may be granted upon compelling or changed circumstances that render continuation of the injunction inequitable'" (Thompson v 76 Corp., 37 AD3d 450, 452-453, quoting Wellbilt Equip. Corp. v. Red Eye Grill, 308 AD2d 411, 411). In this case, the defendant failed to demonstrate that the Supreme Court's conditional granting of that branch of its motion which was to vacate the Yellowstone injunction was an abuse of discretion (see Town of Stanford v Donnelly, 131 AD2d 465). Accordingly, we agree with the court's determination conditionally granting that branch of the defendant's motion which was to vacate the Yellowstone injunction.

We also agree with the Supreme Court's determination denying the defendant's motion for summary judgment dismissing the complaint, and granting the plaintiff's cross motion for summary judgment, inter alia, on so much of its first cause of action as was for a judgment declaring that it did not breach the lease. In support of its cross motion for summary judgment, the plaintiff submitted evidence establishing, prima facie, that it either did not breach the terms of the lease as alleged in the notice to cure or that it cured any alleged default in complying with the lease during the pendency of the Yellowstone injunction (see Graubard Mollen Horowitz Pomeranz & Shapiro v 600 Third Ave. Assoc., 93 NY2d 508, 514; Barsyl Supermarkets, Inc. v Avenue P Assoc., LLC, 86 AD3d 545). In opposition to the plaintiff's showing in this regard, the defendant failed to raise a triable issue of fact.

Since this is, in part, a declaratory judgment action, we remit the matter to the Supreme Court, Kings County, for the entry of a judgment, inter alia, declaring that there was no uncured breach of the lease by the plaintiff (see Lanza v Wagner, 11 NY2d 317, 334)."

Monday, November 25, 2019

Friday, November 22, 2019

NEIGHBOR'S DISPUTE ON WATER RUNOFF BARRED BY STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS

Perhaps he could have resolved this earlier.

Ubiles v. Ngardingabe, NYLJ November 21, 2019, Date filed: 2019-10-31, Court: Supreme Court, New York, Judge: Justice Arlene Bluth. Case Number: 151439/2017:

"Plaintiffs and defendants are neighbors and they own adjoining properties on West 147th Street in Manhattan. Plaintiffs claim that rain water and snow melt flows from defendants’ driveway into plaintiffs’ property. Plaintiffs contend that as a result of this runoff, the foundation and the walls of their home have been damaged. They contend that defendants caused this condition by impermissibly altering the water drainage system in defendants’ driveway and defendants have done nothing to remediate the problem despite plaintiffs’ complaints

Defendants move to dismiss based on the statute of limitations and on plaintiffs’ failure to state a cause of action. Defendants claim that the driveway was installed in 1989 when two lots (431 and 433 West 147th Street) were merged. Defendants argue that the driveway is pitched towards the street and is not causing damage to plaintiffs’ property. Defendants claim that in 2006, plaintiffs requested permission from defendants to access defendants’ driveway to do pointing work and partial waterproofing on plaintiffs’ wall. Defendants contend that by 2009, the work on plaintiffs’ wall was deteriorating and rendered the property vulnerable to damage from rain and snow.

In 2014, plaintiffs again requested access to defendants’ property and defendants insist they allowed plaintiffs to install a tarp over a portion of the subject wall. In May 2015, defendants received a letter from plaintiffs’ attorney arguing that defendants’ actions in 2009 or 2010 (cementing over the existing driveway) were deficient and caused the surface to pitch towards plaintiffs’ property. Defendants admit that the driveway was paved in 2009.

Defendants also point out that they notified their insurance company after receiving this letter from plaintiffs’ counsel but that their insurance company found that the driveway did not contribute to plaintiffs’ damage. Defendants maintain that plaintiffs reached out to plaintiffs’ insurance carrier, who also denied plaintiffs’ claim based on the water runoff.

Defendants argue that this case is time-barred because the driveway was altered, at the latest, eight years before this action was commenced. Defendants also argue that the continuous wrong doctrine does not apply because the damage arises out of a single allegedly objectionable act (the altering of the driveway). Defendants conclude that plaintiffs knew about the damage since at least 2006 and, therefore, they cannot claim a continuing trespass or nuisance.

In opposition, plaintiffs insist they did not know about the source of the water flow until 2015. Plaintiffs purportedly hired an architect in 2015, who found that the water was flowing from defendants’ driveway. Plaintiffs argue that defendants expanded their driveway without the proper approval from the city. Plaintiffs dispute that they knew about the water damage in 2006 even though they claim that every time it rains or snows, their property is inundated with water runoff. Plaintiffs conclude that the water runoff constitutes a trespass to their property.

Discussion

“In moving to dismiss an action as barred by the statute of limitations, the defendant bears the initial burden of demonstrating, prima facie, that the time within which to commence the cause of action has expired. The burden then shifts to the plaintiff to raise a question of fact as to whether the statute of limitations is inapplicable or whether the action was commenced within the statutory period, and the plaintiff must aver evidentiary facts establishing that the action was timely or [] raise an issue of fact as to whether the action was timely” (MTGLQ Investors, LP v. Wozencraft, 2019 WL 2291865, 2019 NY Slip Op 04287 [1st Dept 2019] [internal quotations and citations omitted]).

“The continuous wrong doctrine is an exception to the general rule that the statute of limitations runs from the time of the breach though no damage occurs until later. The doctrine is usually employed where there is a series of continuing wrongs and serves to toll the running of a period of limitations to the date of the commission of the last wrongful act. Where applicable, the doctrine will save all claims for recovery of damages but only to the extent of wrongs committed within the applicable statute of limitations. The doctrine may only be predicated on continuing unlawful acts and not on the continuing effects of earlier unlawful conduct. The distinction is between a single wrong that has continuing effects and a series of independent, distinct wrongs. The doctrine is inapplicable where there is one tortious act complained of since the cause of action accrues in those cases at the time that the wrongful act first injured plaintiff and it does not change as a result of continuing consequential damages” (Henry v. Bank of America, 147 AD3d 599, 601 48 NYS3d 67 [1st Dept 2017] [internal quotations and citations omitted]).

Here, the Court finds that the instant action is barred by the statute of limitations. This case was filed in 2017. The allegedly unlawful acts were either the construction of the driveway in 1989 or the paving of the driveway in 2009. Both of these acts (which purportedly caused the water runoff) occurred prior to the three-year statute of limitations applicable to plaintiffs’ causes of action. Plaintiffs do not allege that defendants did anything else to cause the water runoff. Therefore, the Court finds that, assuming plaintiffs’ claims are true, the paving of the driveway in 2009 was a single and distinct wrong that has had purportedly continuing effects rather than a series of independent acts. Put another way, because defendants have not altered the driveway since 2009, the water runoff when it rains or snows are not new wrongful acts by defendants.

Moreover, the record shows plaintiffs were experiencing water runoff problems since at least 2006. The letter correspondence between the parties makes clear that plaintiffs needed to have work done to keep their basement dry (NYSCEF Doc. No. 78). In fact, the parties’ communications show that a wall was built by plaintiffs in 2006 for “drainage enhancement” (id.). In other words, plaintiffs clearly had water problems in 2006 and took actions to try and remediate the problem more than three years before they brought this action.

The opposition, an affidavit from plaintiff Joseph Ubiles, conveniently skips from a conclusory assertion that defendants’ driveway had nothing to do with the 2006 work to 2015 (NYSCEF Doc. No. 86,10-15). There is no explanation for why they did not seek to discover the cause of the water issues in 2006 despite the fact that they needed access to defendants’ property to do the work. And that work involved the construction of a wall that defendants’ claim was impermissibly built on their property. That plaintiffs waited until 2015 to hire an architect, who claims that the water runoff was from defendants’ driveway, does not extend the statute of limitations. Plaintiffs cannot sit on their rights for over a decade after their property suffered water damage. Therefore, plaintiffs’ claims are untimely (see Alamio v. Town of Rockland, 302 AD2d 842, 755 NYS2d 754 [3d Dept 2003] [finding that continuing trespass and nuisance claims arising out of water runoff from an adjacent parking lot were time-barred because the damage was apparent more than three years prior to the commencement of the action]).:

In 2014, plaintiffs again requested access to defendants’ property and defendants insist they allowed plaintiffs to install a tarp over a portion of the subject wall. In May 2015, defendants received a letter from plaintiffs’ attorney arguing that defendants’ actions in 2009 or 2010 (cementing over the existing driveway) were deficient and caused the surface to pitch towards plaintiffs’ property. Defendants admit that the driveway was paved in 2009.

Defendants also point out that they notified their insurance company after receiving this letter from plaintiffs’ counsel but that their insurance company found that the driveway did not contribute to plaintiffs’ damage. Defendants maintain that plaintiffs reached out to plaintiffs’ insurance carrier, who also denied plaintiffs’ claim based on the water runoff.

Defendants argue that this case is time-barred because the driveway was altered, at the latest, eight years before this action was commenced. Defendants also argue that the continuous wrong doctrine does not apply because the damage arises out of a single allegedly objectionable act (the altering of the driveway). Defendants conclude that plaintiffs knew about the damage since at least 2006 and, therefore, they cannot claim a continuing trespass or nuisance.

In opposition, plaintiffs insist they did not know about the source of the water flow until 2015. Plaintiffs purportedly hired an architect in 2015, who found that the water was flowing from defendants’ driveway. Plaintiffs argue that defendants expanded their driveway without the proper approval from the city. Plaintiffs dispute that they knew about the water damage in 2006 even though they claim that every time it rains or snows, their property is inundated with water runoff. Plaintiffs conclude that the water runoff constitutes a trespass to their property.

Discussion

“In moving to dismiss an action as barred by the statute of limitations, the defendant bears the initial burden of demonstrating, prima facie, that the time within which to commence the cause of action has expired. The burden then shifts to the plaintiff to raise a question of fact as to whether the statute of limitations is inapplicable or whether the action was commenced within the statutory period, and the plaintiff must aver evidentiary facts establishing that the action was timely or [] raise an issue of fact as to whether the action was timely” (MTGLQ Investors, LP v. Wozencraft, 2019 WL 2291865, 2019 NY Slip Op 04287 [1st Dept 2019] [internal quotations and citations omitted]).

“The continuous wrong doctrine is an exception to the general rule that the statute of limitations runs from the time of the breach though no damage occurs until later. The doctrine is usually employed where there is a series of continuing wrongs and serves to toll the running of a period of limitations to the date of the commission of the last wrongful act. Where applicable, the doctrine will save all claims for recovery of damages but only to the extent of wrongs committed within the applicable statute of limitations. The doctrine may only be predicated on continuing unlawful acts and not on the continuing effects of earlier unlawful conduct. The distinction is between a single wrong that has continuing effects and a series of independent, distinct wrongs. The doctrine is inapplicable where there is one tortious act complained of since the cause of action accrues in those cases at the time that the wrongful act first injured plaintiff and it does not change as a result of continuing consequential damages” (Henry v. Bank of America, 147 AD3d 599, 601 48 NYS3d 67 [1st Dept 2017] [internal quotations and citations omitted]).

Here, the Court finds that the instant action is barred by the statute of limitations. This case was filed in 2017. The allegedly unlawful acts were either the construction of the driveway in 1989 or the paving of the driveway in 2009. Both of these acts (which purportedly caused the water runoff) occurred prior to the three-year statute of limitations applicable to plaintiffs’ causes of action. Plaintiffs do not allege that defendants did anything else to cause the water runoff. Therefore, the Court finds that, assuming plaintiffs’ claims are true, the paving of the driveway in 2009 was a single and distinct wrong that has had purportedly continuing effects rather than a series of independent acts. Put another way, because defendants have not altered the driveway since 2009, the water runoff when it rains or snows are not new wrongful acts by defendants.

Moreover, the record shows plaintiffs were experiencing water runoff problems since at least 2006. The letter correspondence between the parties makes clear that plaintiffs needed to have work done to keep their basement dry (NYSCEF Doc. No. 78). In fact, the parties’ communications show that a wall was built by plaintiffs in 2006 for “drainage enhancement” (id.). In other words, plaintiffs clearly had water problems in 2006 and took actions to try and remediate the problem more than three years before they brought this action.

The opposition, an affidavit from plaintiff Joseph Ubiles, conveniently skips from a conclusory assertion that defendants’ driveway had nothing to do with the 2006 work to 2015 (NYSCEF Doc. No. 86,10-15). There is no explanation for why they did not seek to discover the cause of the water issues in 2006 despite the fact that they needed access to defendants’ property to do the work. And that work involved the construction of a wall that defendants’ claim was impermissibly built on their property. That plaintiffs waited until 2015 to hire an architect, who claims that the water runoff was from defendants’ driveway, does not extend the statute of limitations. Plaintiffs cannot sit on their rights for over a decade after their property suffered water damage. Therefore, plaintiffs’ claims are untimely (see Alamio v. Town of Rockland, 302 AD2d 842, 755 NYS2d 754 [3d Dept 2003] [finding that continuing trespass and nuisance claims arising out of water runoff from an adjacent parking lot were time-barred because the damage was apparent more than three years prior to the commencement of the action]).:

Thursday, November 21, 2019

NOT A HOSTILE WORK ENVIRONMENT?

It depends - actions can be despicable but not deemed a hostile work environment.

Lawrence v. Chemprene, Inc., No. 18-CV-2537 (CS) (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 24, 2019) :

"B. Hostile Work Environment

Defendants argue that Plaintiff’s hostile work environment claims should be dismissed because, among other things, Plaintiff has failed to allege that Defendants’ conduct was sufficiently severe and pervasive. (Ds’ Mem. at 11-16.) I agree.

“‘To establish a hostile work environment claim…a plaintiff must produce enough evidence to show that the workplace is permeated with discriminatory intimidation, ridicule, and insult, that is sufficiently severe or pervasive to alter the conditions of the victim’s employment and create an abusive working environment.’” Davis v. N.Y. Dep’t of Corr., 256 F. Supp. 3d 343, 350 (S.D.N.Y. 2017) (alteration omitted) (quoting Rivera v. Rochester Genesee Regional Transp. Auth., 743 F.3d 11, 20 (2d Cir. 2014)); see Smith v. Town of Hempstead Dep’t of Sanitation Sanitary Dist. No. 2, 798 F. Supp. 2d 443, 451 (E.D.N.Y. 2011) (hostile work environment standard “is essentially the same” for Title VII, §1981, and NYHRL claims), reconsideration denied, 982 F. Supp. 2d 225 (E.D.N.Y. 2013), motion for relief from judgment denied, No. 08-CV-3546, 2014 WL 12839299 (E.D.N.Y. Feb. 6, 2014). “In considering whether a plaintiff has met this burden, courts should examine the totality of the circumstances, including: the frequency of the discriminatory conduct; its severity; whether it is physically threatening or humiliating, or a mere offensive utterance; and whether it unreasonably interferes with the victim’s job performance.” Rivera, 743 F.3d at 20 (internal quotation marks and alterations omitted). The test is both objective and subjective: “the misconduct shown must be severe or pervasive enough to create an objectively hostile or abusive work environment, and the victim must also subjectively perceive that environment to be abusive.” Id. (internal quotation marks omitted). “Of course, it is axiomatic that mistreatment at work, whether through subjection to a hostile environment or through other means, is actionable under Title VII only when it occurs because of an employee’s protected characteristic, such as race or national origin.” Id. (internal quotation marks and alterations omitted) (emphasis in original).

While Plaintiff did not file a memorandum of law in opposition to Defendants’ motion, Plaintiff’s 56.1 Response, read in the light most favorable to him, includes the following allegations that go his hostile work environment claim: (1) in December 2007, Plaintiff was told that Arvelo told Simmons, “[T]ell that black [motherfucker] to order bags,” in reference to Plaintiff, (P’s 56.1 Resp

“‘To establish a hostile work environment claim…a plaintiff must produce enough evidence to show that the workplace is permeated with discriminatory intimidation, ridicule, and insult, that is sufficiently severe or pervasive to alter the conditions of the victim’s employment and create an abusive working environment.’” Davis v. N.Y. Dep’t of Corr., 256 F. Supp. 3d 343, 350 (S.D.N.Y. 2017) (alteration omitted) (quoting Rivera v. Rochester Genesee Regional Transp. Auth., 743 F.3d 11, 20 (2d Cir. 2014)); see Smith v. Town of Hempstead Dep’t of Sanitation Sanitary Dist. No. 2, 798 F. Supp. 2d 443, 451 (E.D.N.Y. 2011) (hostile work environment standard “is essentially the same” for Title VII, §1981, and NYHRL claims), reconsideration denied, 982 F. Supp. 2d 225 (E.D.N.Y. 2013), motion for relief from judgment denied, No. 08-CV-3546, 2014 WL 12839299 (E.D.N.Y. Feb. 6, 2014). “In considering whether a plaintiff has met this burden, courts should examine the totality of the circumstances, including: the frequency of the discriminatory conduct; its severity; whether it is physically threatening or humiliating, or a mere offensive utterance; and whether it unreasonably interferes with the victim’s job performance.” Rivera, 743 F.3d at 20 (internal quotation marks and alterations omitted). The test is both objective and subjective: “the misconduct shown must be severe or pervasive enough to create an objectively hostile or abusive work environment, and the victim must also subjectively perceive that environment to be abusive.” Id. (internal quotation marks omitted). “Of course, it is axiomatic that mistreatment at work, whether through subjection to a hostile environment or through other means, is actionable under Title VII only when it occurs because of an employee’s protected characteristic, such as race or national origin.” Id. (internal quotation marks and alterations omitted) (emphasis in original).

While Plaintiff did not file a memorandum of law in opposition to Defendants’ motion, Plaintiff’s 56.1 Response, read in the light most favorable to him, includes the following allegations that go his hostile work environment claim: (1) in December 2007, Plaintiff was told that Arvelo told Simmons, “[T]ell that black [motherfucker] to order bags,” in reference to Plaintiff, (P’s 56.1 Resp

13-14); (2) Rodriguez told Plaintiff that Patinella had called him a “stupid nigger,” (id.

22);13 (3) Kiene drew a penis on a mixing bag, (id.

37); Kiene made a statement to the effect of “the police should shoot all the blacks,” (id.

41); and (5) Ford wrote something to the effect of “that’s a nigger job” on the sheet of paper assigning Ford to clean the pit, (id.

29). These allegations, however revolting they may be, fall short of establishing a hostile work environment.

Plaintiff’s first allegation supporting his hostile work environment claim was a derogatory statement that he did not hear directly, but rather of which he learned from a coworker. He was told by Simmons that Arvelo called him a “black motherfucker.” (P’s 56.1

13.) While secondhand statements “should not be ignored,” such statements “are not as impactful on one’s environment as are direct statements; consequently, they are less persuasive in stating a hostile work environment claim.” Sletten v. LiquidHub, Inc., No. 13-CV-1146, 2014 WL 3388866, at *7 (S.D.N.Y. July 11, 2014). Further, Defendant immediately fired Arvelo. (P’s 56.1 Resp.

15.) Where the harasser is a non-supervisory coworker, the employer is not liable for that harassment unless it knew of the conduct and failed to take appropriate remedial action. See Wiercinski v. Mangia 57, Inc., 787 F.3d 106, 113 (2d Cir. 2015); Whidbee v. Garzarelli Food Specialties, Inc., 223 F.3d 62, 72 (2d Cir. 2000). Because Defendants took swift remedial action, Plaintiff cannot support his claim of hostile work environment with Arvelo’s statement.

Plaintiff’s second allegation is that Rodriguez told Plaintiff that Patinella called Plaintiff a “stupid nigger.” (P’s 56.1 Resp.

22.) As noted above, that allegation — which by Plaintiff’s account was in any event also outside his presence — must be disregarded because it contradicts Plaintiff’s deposition testimony.14

Plaintiff’s third allegation has to do with a penis drawn on a mixing bag, (id.

37), but Plaintiff failed to indicate how the drawing was discriminatory toward Plaintiff on account of his race. Rather, Plaintiff merely states that “[Simmons] went to HR about a racist incident involving Kiene but nothing was done,” (id.

37), without providing a single detail regarding the incident, how it was racist, or how it injured Plaintiff. Perhaps the racist incident to which Plaintiff is referring is his fourth allegation — Kiene’s statement that “police should shoot all the blacks” — but Plaintiff never makes that connection. In any event, Kiene was also terminated after a thorough investigation, so his misconduct cannot be attributed to Defendants.

Plaintiff’s fifth allegation has to do with Ford writing the N word on an assignment sheet. (Id.

29.) While any use of that word is a despicable act, there is nothing in the record to suggest that the note was directed at Plaintiff. There is no evidence that Plaintiff assigned Ford to clean the pit, that Plaintiff created the assignment sheet that Ford defaced, or that Ford wrote the note for Plaintiff specifically, as opposed to writing it for the whole mixing department to see. While “racial epithets need not be directed at an employee to contribute to a hostile work environment,” Abdullah v. Panko Elec. & Maint., Inc., No. 08-CV-0579, 2011 WL 1103762, at *13 (N.D.N.Y. Mar. 23, 2011), “whether racial slurs constitute a hostile work environment typically depends upon the quantity, frequency, and severity of those slurs,” Schwapp v. Town of Avon, 118 F.3d 106, 110-11 (2d Cir. 1997) (internal quotation marks omitted), and the severity is reduced when the slur is not directed at the plaintiff himself, see Hill v. Frontier Tel. of Rochester, Inc., No. 15-CV-6212, 2018 WL 1256220, at *6 (W.D.N.Y. Mar. 12, 2018).

In sum, Plaintiff has alleged one secondhand comment that cannot be attributed to Defendants, a racist remark that also cannot be attributed to Defendants, a lewd drawing, and one use of a racial epithet that was not directed at Plaintiff, all over the course of nine years. Not one of the incidents was physically threatening. Courts have dismissed hostile work environment claims as insufficiently severe and pervasive that are based on a greater number of incidents, including more severe forms of discrimination, over a shorter period. See Alfano v. Costello, 294 F.3d 365, 379 (2d Cir. 2002) (collecting cases); see Stembridge v. City of N.Y., 88 F. Supp. 2d 276, 286 (S.D.N.Y. 2000) (seven racially insensitive comments over three years, including one instance of calling the plaintiff the N word, were not pervasive).

Moreover, Plaintiff has “proffered no evidence that the alleged harassment interfered with [his] job performance, a sine qua non of such a claim, notwithstanding that…[the] comments may have been offensive.” Stepheny v. Brooklyn Hebrew Sch. for Special Children, 356 F. Supp. 2d 248, 265 (E.D.N.Y. 2005) (internal quotation marks and alterations omitted). Accordingly, I find that Plaintiff cannot establish a hostile work environment claim under Title VII, §1981, or the NYHRL, and Defendants are entitled to summary judgment on those claims.15"

22);13 (3) Kiene drew a penis on a mixing bag, (id.

37); Kiene made a statement to the effect of “the police should shoot all the blacks,” (id.

41); and (5) Ford wrote something to the effect of “that’s a nigger job” on the sheet of paper assigning Ford to clean the pit, (id.

29). These allegations, however revolting they may be, fall short of establishing a hostile work environment.

Plaintiff’s first allegation supporting his hostile work environment claim was a derogatory statement that he did not hear directly, but rather of which he learned from a coworker. He was told by Simmons that Arvelo called him a “black motherfucker.” (P’s 56.1

13.) While secondhand statements “should not be ignored,” such statements “are not as impactful on one’s environment as are direct statements; consequently, they are less persuasive in stating a hostile work environment claim.” Sletten v. LiquidHub, Inc., No. 13-CV-1146, 2014 WL 3388866, at *7 (S.D.N.Y. July 11, 2014). Further, Defendant immediately fired Arvelo. (P’s 56.1 Resp.

15.) Where the harasser is a non-supervisory coworker, the employer is not liable for that harassment unless it knew of the conduct and failed to take appropriate remedial action. See Wiercinski v. Mangia 57, Inc., 787 F.3d 106, 113 (2d Cir. 2015); Whidbee v. Garzarelli Food Specialties, Inc., 223 F.3d 62, 72 (2d Cir. 2000). Because Defendants took swift remedial action, Plaintiff cannot support his claim of hostile work environment with Arvelo’s statement.

Plaintiff’s second allegation is that Rodriguez told Plaintiff that Patinella called Plaintiff a “stupid nigger.” (P’s 56.1 Resp.

22.) As noted above, that allegation — which by Plaintiff’s account was in any event also outside his presence — must be disregarded because it contradicts Plaintiff’s deposition testimony.14

Plaintiff’s third allegation has to do with a penis drawn on a mixing bag, (id.

37), but Plaintiff failed to indicate how the drawing was discriminatory toward Plaintiff on account of his race. Rather, Plaintiff merely states that “[Simmons] went to HR about a racist incident involving Kiene but nothing was done,” (id.

37), without providing a single detail regarding the incident, how it was racist, or how it injured Plaintiff. Perhaps the racist incident to which Plaintiff is referring is his fourth allegation — Kiene’s statement that “police should shoot all the blacks” — but Plaintiff never makes that connection. In any event, Kiene was also terminated after a thorough investigation, so his misconduct cannot be attributed to Defendants.

Plaintiff’s fifth allegation has to do with Ford writing the N word on an assignment sheet. (Id.

29.) While any use of that word is a despicable act, there is nothing in the record to suggest that the note was directed at Plaintiff. There is no evidence that Plaintiff assigned Ford to clean the pit, that Plaintiff created the assignment sheet that Ford defaced, or that Ford wrote the note for Plaintiff specifically, as opposed to writing it for the whole mixing department to see. While “racial epithets need not be directed at an employee to contribute to a hostile work environment,” Abdullah v. Panko Elec. & Maint., Inc., No. 08-CV-0579, 2011 WL 1103762, at *13 (N.D.N.Y. Mar. 23, 2011), “whether racial slurs constitute a hostile work environment typically depends upon the quantity, frequency, and severity of those slurs,” Schwapp v. Town of Avon, 118 F.3d 106, 110-11 (2d Cir. 1997) (internal quotation marks omitted), and the severity is reduced when the slur is not directed at the plaintiff himself, see Hill v. Frontier Tel. of Rochester, Inc., No. 15-CV-6212, 2018 WL 1256220, at *6 (W.D.N.Y. Mar. 12, 2018).

In sum, Plaintiff has alleged one secondhand comment that cannot be attributed to Defendants, a racist remark that also cannot be attributed to Defendants, a lewd drawing, and one use of a racial epithet that was not directed at Plaintiff, all over the course of nine years. Not one of the incidents was physically threatening. Courts have dismissed hostile work environment claims as insufficiently severe and pervasive that are based on a greater number of incidents, including more severe forms of discrimination, over a shorter period. See Alfano v. Costello, 294 F.3d 365, 379 (2d Cir. 2002) (collecting cases); see Stembridge v. City of N.Y., 88 F. Supp. 2d 276, 286 (S.D.N.Y. 2000) (seven racially insensitive comments over three years, including one instance of calling the plaintiff the N word, were not pervasive).

Moreover, Plaintiff has “proffered no evidence that the alleged harassment interfered with [his] job performance, a sine qua non of such a claim, notwithstanding that…[the] comments may have been offensive.” Stepheny v. Brooklyn Hebrew Sch. for Special Children, 356 F. Supp. 2d 248, 265 (E.D.N.Y. 2005) (internal quotation marks and alterations omitted). Accordingly, I find that Plaintiff cannot establish a hostile work environment claim under Title VII, §1981, or the NYHRL, and Defendants are entitled to summary judgment on those claims.15"

Wednesday, November 20, 2019

FREE HOUSING IN LIEU OF CHILD SUPPORT?

I found the facts of this case interesting.

Herbert v. Maranga, NYLJ November 07, 2019, Date filed: 2019-10-24, Court: Appellate Term, First Department. Judge: Per Curiam, Case Number: 570443/19:

"Respondents Margaret Maranga and Adam Oyunge appeal from a final judgment of the Civil Court of the City of New York, New York County (Sabrina B. Kraus, J.), entered May 15, 2019, after a nonjury trial, which awarded possession to petitioner in a holdover summary proceeding. PER CURIAM Final judgment (Sabrina B. Kraus, J.), entered May 15, 2019, reversed, with $30 costs, and a final judgment awarded in favor of respondents dismissing the petition, without prejudice.

Petitioner, the sole owner of a condominium apartment, sought possession of the premises from his former paramour, respondent Margaret Maranga, and their son, respondent Adam Oyunge, based on the termination of an oral month-to-month tenancy. The evidence at trial showed that Adam was born as the result of an affair between petitioner and Maranga. When Adam was about four years old, Maranga needed a larger apartment and wanted to live in a neighborhood that had a good public school for Adam to attend. As a result, petitioner, who never resided with respondents, purchased the Third Avenue apartment at issue. Both petitioner and Maranga testified as to their respective versions of an oral agreement permitting respondents to occupy the apartment. The trial court credited substantially petitioner’s testimony that the parties’ agreed that petitioner would purchase the subject condominium “in lieu of paying child support” so that respondents could reside there until Adam turned 21 years of age or “old enough to be on his own.” Since Adam was 21 years old at the time of trial, the court awarded petitioner possession.

Exercising our authority to review the record developed at a the nonjury trial (see Northern Westchester Professional Park Assoc. v. Town of Bedford, 60 NY2d 494, 499 [1983]), and accepting the court’s fully supported findings of fact and credibility, including its finding that petitioner agreed that respondents “could live in the subject premises until [Adam] was emancipated,” we find that Civil Court should have dismissed the proceeding as premature. Adam had not yet turned 21 when this proceeding was commenced and petitioner offered insufficient evidence at trial that Adam was “old enough to be on his own.” In the circumstances presented, the petition was prematurely commenced and should have been dismissed without prejudice. Since Adam has since turned 21 years of age, our disposition is without prejudice to any future proceeding. We reach no other issue."

Tuesday, November 19, 2019

Monday, November 18, 2019

AN AMBIGUOUS DIVORCE AGREEMENT

Abadi v Abadi, 2019 NY Slip Op 08168, Decided on November 13, 2019, Appellate Division, Second Department:

"We agree with the Supreme Court's determination that the postnuptial agreement was ambiguous and that the evidence adduced at the hearing revealed that the parties intended the defendant to have a minimum monthly child support obligation of $1,250. "A stipulation of settlement which is incorporated but not merged into a judgment of divorce is a contract subject to the principles of contract construction and interpretation" (Matter of Tannenbaum v Gilberg, 134 AD3d 846, 847; see Ayers v Ayers, 92 AD3d 623, 624). Whether a writing is ambiguous is a matter of law for the court, and the proper inquiry is " whether the agreement on its face is reasonably susceptible of more than one interpretation'" (Clark v Clark, 33 AD3d 836, 837, quoting Chimart Assoc. v Paul, 66 NY2d 570, 573; see Salinger v Salinger, 125 AD3d 747, 749; Ayers v Ayers, 92 AD3d at 625).

Here, the relevant provisions of the postnuptial agreement are ambiguous (see Salinger v Salinger, 125 AD3d at 749). Paragraph 6.2 of the postnuptial agreement provides that the defendant shall pay monthly child support in an amount "equal to the sum of (a) 20% of his gross income from all sources up to the first $125,000 of his gross income plus (b) 25% of his gross income from all sources above $125,000 and up to $500,000, until such time as the parties' Children are emancipated." Paragraph 6.3 provides that "[b]ased on the [defendant's] current annual gross income of approximately $75,000 commencing on or before May 1, 2011, the [defendant] shall pay to the [plaintiff] the sum of ONE THOUSAND TWO HUNDRED AND FIFTY ($1,250) DOLLARS per month, as and for the direct support and maintenance of the parties' Children." Paragraph 6.4 provides that "[o]n or before January 30 of each year, to the extent that the [defendant]'s gross income from all sources was greater than $75,000 for the just completed calendar year, the [defendant] shall pay additional direct child support so that his direct child support payments for the prior completed calendar year satisfy the requirements of paragraph 6.2 above. In addition, his monthly direct child support obligations for the current calendar year shall be increased in accordance with paragraph 6.2 . . . The [defendant]'s direct child support obligation shall never be less than the amount set forth in paragraph 6.2 above." These provisions are ambiguous as to whether the parties intended the defendant to have a minimum child support obligation, given that paragraph 6.4 refers to the amount set forth in paragraph 6.2, but paragraph 6.2 provides for child support based on certain percentages of income, and paragraph 6.4 refers to the payment of "additional" and "increased" child support payments, which suggests that there is a minimum child support obligation.

"Where a stipulation of settlement is susceptible of differing interpretations and is thus ambiguous, a court is entitled to rely upon the language of the entire agreement and the circumstances surrounding its execution in construing the provision'" (Palaia v Palaia, 158 AD3d 719, 720-721, quoting Noren v Babus, 144 AD3d 762, 764; see Driscoll v Driscoll, 45 AD3d 723). Thus, extrinsic evidence of the parties' intent may be considered if the agreement is ambiguous (see Greenfield v Philles Records, 98 NY2d 562, 566).

Here, the evidence adduced at the hearing included the plaintiff's testimony, a draft version of the postnuptial agreement, and a sworn statement of net worth dated February 8, 2015, in which the defendant stated that he had no income in 2015 but had a monthly expense of $1,250 for child support. This evidence reveals that the parties intended that the defendant's monthly child support obligation would never be less than the amount set forth in paragraph 6.3, $1,250 per month, and that the reference to "the amount set forth in paragraph 6.2" was a typographical error. Moreover, we accord deference to the Supreme Court's determination that the plaintiff testified credibly regarding the parties' intent and that the defendant was evasive as to this issue (see Cutroneo v Cutroneo, 140 AD3d 1006, 1009)."

Friday, November 15, 2019

ADOPTEES' RIGHT TO RECEIVE BIRTH CERTIFICATE

Just signed into law yesterday. Below are the memorandums from the NYS senate bill :

"BILL NUMBER: S3419 SPONSOR: MONTGOMERY TITLE OF BILL: An act to amend the public health law and the domestic relations law, in relation to authorizing adoptees to obtain a certified copy of their birth certificate PURPOSE OR GENERAL IDEA OF BILL: Restores the civil right of adult adoptees to receive a certified copy of their original long form birth certificate if 18 years of age or older. The specific provisions are intended to ensure that all adult adoptees adopted in New York will have the same unimpeded right as non- adopted people born in New York to access such birth certificates or, if not available, the true and correct information that would have appeared on them. SUMMARY OF PROVISIONS: Section 1 of the bill amends the public health law by adding a new section, § 4138-e. It is premised on an acknowledgment that the truth of

one's origins should be a birthright. Accordingly, the new § 4138-e affirms, supports and encourages the life-long health and well-being needs of adoptees, and those who will be adopted in the future, by restoring the right of all adult adopted persons born or adopted in New York to unrestricted access to their original birth certificates. The denial of access to accurate and complete self-identifying and medical information of any adopted person is a violation of that person's human rights and is contrary to the tenets of governance. Section 1 provides that an adopted person eighteen years of age, or if the adopted person is deceased, the adopted person's direct line descendants, or the lawful representatives of such adopted person, or lawful representatives of such deceased adopted person's direct line descendants can obtain a certified copy of the adopted person's original long form birth certificate, from the commissioner or a local registrar, in the same manner as such certificates are available to persons born in the state of New York who were not adopted. The amendment also requires the commissioner to provide the adopted person or other authorized person with the background information about the adopted child and the adopted child's birth parents sent to the commissioner pursuant to subdivision 1 of § 114 of the domestic relations law. In addition, in the event that the commissioner does not have the original birth certificate of an adopted person, section 1 requires courts and other agencies that have records containing the information that would have appeared on the adopted person's original long form birth certificate to provide such information, including all identifying information about the adopted person's birth parents, to the adult adopted person or other authorized person upon a simple written request therefor that includes proof of identity. Section 2 amends subdivision 4 of § 4138 of the public health law to authorize the commissioner to make microfilm or other suitable copies of an original certificate of birth in accordance with newly added section 4138-e. Section 2 amends subdivision 4 of § 4138 of the public health law to authorize the commissioner to provide a certified copy of the original long form certificate of birth to an adult adopted person in accordance with § 4138-e of the public health law. Section 3 amends subdivision 5 of § 4138 of the public health law to state that a certified copy of the original long form certificate of birth of such a person shall be issued to an adult adopted person in accordance with § 4138-e of the public health law. Section 4 amends paragraph (a) of subdivision 3 of § 4138 of the public health law to authorize a local registrar to provide a certified copy of the original long form certificate of birth to an adult adopted person in accordance with § 4138-e of the public health law. Section 5 amends paragraph (b) of subdivision 3 of § 4138 of the public health law to authorize a local registrar to provide a certified copy of the original long form certificate of birth to an adult adopted person in accordance with § 4138-e of the public health law. Section 6 adds a new subdivision 8 to § 4138 of the public health law to authorize adopted persons eighteen years of age or older, or the birth parent (s), to submit a change of name and/or address to be attached to the original birth certificate of the adopted person. Section 7 amends § 4138-d of the public health law to remove the provision that allows an adoption agency to restrict access to non-iden- tifying information that is not in the best interest of the adoptee, the biological sibling or the birth parent(s). Section 8 amends § 4104 of the public health law to include additional provisions under vital statistics that would be applicable to the city of New York. Section 9 amends subdivision 1 of § 114 of the domestic relations law to require that any order of adoption direct that the information to be provided to the adoptive parents about the child and the child's birth parents shall include the child's and birthparents' information at the time of surrender and, in addition, that the information provided to the adoptive parents also be provided to the commissioner of health. Section 10 is the effective date. JUSTIFICATION: The bill will restore adult adoptees' right to access information that non-adopted persons, including those who "age-out" of foster care, have a legal right to obtain. In New York, an adopted person cannot access his or her original birth certificate unless the adopted person goes through a judicial proceeding and, even then, the outcome does not guar- antee that access will be granted. This bill will allow adult adoptees, or if the adopted person is deceased, the adopted person's direct line descendants, or the lawful representatives of such adopted person (living) or lawful representatives of such deceased adopted person's direct line descendants, to obtain a certified copy of the adopted person's original long form birth certificate. Adoptees will continue, under existing law, to be able to secure "non-identifying" information which may include, but not be limited to, their religious and ethnic heritage and medical history information that may be necessary for preventive health care and the treatment of illnesses linked to family history and genetics. To whatever extent "non-identifying" information may be unavailable, the restoration of the civil right to one's own original birth certificate will restore equal opportunity for seeking such information. PRIOR LEGISLATIVE HISTORY: 2018: A9959-B / S7631-B 2017-2018:A.5036-B/S.4845-B -vetoed by governor 2015-2016: A.2901/S3314, followed by A.2901-A/S.5964 -Passed Assembly 2013-2014: A909/S2490 2012: A.8910/S.7286 2011: A.2003/S.1438 2009/2010: A.8410A/S.5269A 2007/2008: A.2277/S.235 2006: A.9823/S.446 2005: A.928/S.446 2003-2004: A.6238A/S.2631A 2001-2002: A.7943/S.4286 1999-2000: A.7541A/S.1224A 1997-1998: A.4316/S.3677 1995-1996: A.2328/S.3709A 1993-1994: A.10403/S.856 FISCAL IMPLICATIONS FOR STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS: None. EFFECTIVE DATE: This act shall take effect on January 15, 2020, provided, however, that, effective immediately, the commissioner of health is directed to promul- gate such rules and regulations as may be necessary to carry out the provisions of this act."

Thursday, November 14, 2019

DIVORCE AND MARITAL RESIDENCE

Santamaria v Santamaria, 2019 NY Slip Op 08239, Decided on November 13, 2019, Appellate Division, Second Department:

"The defendant contends that the Supreme Court should not have awarded

the plaintiff a separate property credit in the sum of $332,000 related

to the marital residence. The plaintiff contends that the court should

have awarded him sole title to the marital residence, and should not

have awarded the defendant 50% of any equity in the marital residence

that accrued from 2002 until the date of sale.

"Equitable distribution presents issues of fact to be resolved by the

trial court and should not be disturbed on appeal unless shown to be an

improvident exercise of discretion" (Loria v Loria, 46 AD3d 768,

769-770). "Equitable distribution does not necessarily mean equal

distribution," and requires the court's consideration of all relevant

statutory factors (Faello v Faello, 43 AD3d 1102, 1103; see Domestic Relations Law § 236[B][5][d]).

Here, on the record presented, the Supreme Court providently

exercised its discretion in awarding the plaintiff a separate property

credit of $332,000 related to the marital residence, and awarding the

defendant a 50% share of any equity in the residence that accrued from

2002 until the date of its sale. The evidence at trial demonstrated that

in 2002, the plaintiff's mother transferred ownership of the subject

property, where she resided, to the plaintiff and retained a life estate

in the property. In 2010, after the death of plaintiff's mother, the

plaintiff transferred ownership of the property to himself and the

defendant. At the time, the property was appraised at a value of

$332,000. In 2011, after renovations were conducted, the parties and

their children moved to the property, and it became the marital

residence.

The plaintiff's conveyance of the home in 2010 to himself and the

defendant presumptively changed the character of the home from separate

property to marital property (see Nidositko v Nidositko, 92 AD3d 653; D'Elia v D'Elia, 14 AD3d 477, 478; Diaco v Diaco,

278 AD2d 358, 359). We agree with the court's determination to award

the plaintiff a separate property credit in the amount at which the

residence was valued at the time the property was transferred to both

parties (see Nidositko v Nidositko, 92 AD3d at 654; Monks v Monks, 134 AD2d 334, 335; Coffey v Coffey,

119 AD2d 620, 622). Furthermore, in light of the evidence that

significant marital funds were used over the years to help preserve the

plaintiff's separate property asset, the court providently exercised its

discretion in awarding the defendant 50% of any equity in the marital

residence that accrued from 2002 until the date of its sale."

Wednesday, November 13, 2019

DELAYS IN CONSTRUCTION CONTRACTS AND EXCULPATORY CLAUSES

Arnell Constr. Corp. v New York City Sch. Constr. Auth., 2019 NY Slip Op 07887, Decided on November 6, 2019, Appellate Division, Second Department:

"Generally, contract clauses barring a contractor from recovering damages for delay in the performance of a contract are valid, and "they will prevent recovery of damages resulting from a broad range of reasonable and unreasonable conduct by the contractee if the conduct was contemplated by the parties when they entered into the agreement" (Corinno Civetta Constr. Corp. v City of New York, 67 NY2d 297, 305). However, "[i]t has been settled for some time that [*2]exculpatory clauses will not bar claims resulting from delays caused by the contractee if the delays or their causes were not within the contemplation of the parties at the time they entered into the contract" (id. at 309-310; see Peckham Rd. Co. v State of New York, 32 AD2d 139, 141, affd 28 NY2d 734). "Thus, even broadly worded exculpatory clauses . . . are generally held to encompass only those delays which are reasonably foreseeable, arise from the contractor's work during performance, or which are mentioned in the contract" (Corinno Civetta Constr. Corp. v City of New York, 67 NY2d at 310; see Peckham Rd. Co. v State of New York, 32 AD2d at 141). "A no-damage-for-delay clause must be construed strictly against the drafter of the provision" (Forward Indus. v Rolm of N.Y. Corp., 123 AD2d 374, 376). Furthermore, even where the parties' contract contains such an exculpatory clause and the delay at issue was contemplated therein, damages may be recovered for delays which: were caused by the contractee's bad faith or willful, malicious, or grossly negligent conduct; were so unreasonable that they constitute an intentional abandonment of the contract by the contractee; or resulted from the contractee's breach of a fundamental obligation of the contract (see Corinno Civetta Constr. Corp. v City of New York, 67 NY2d at 309; Kalisch-Jarcho, Inc. v City of New York, 58 NY2d 377, 384-386)."

Tuesday, November 12, 2019

RPAPL 1304 DEFENSE NOT PROVEN

An example of where a court feels that documents speak louder than words.

JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. v Skluth, 2019 NY Slip Op 07886, Decided on November 6, 2019, Appellate Division, Second Department:

"In a residential foreclosure action, a plaintiff moving for summary judgment must tender "sufficient evidence demonstrating the absence of material issues as to its strict compliance with RPAPL 1304" (Aurora Loan Servs., LLC v Weisblum, 85 AD3d 95, 106). RPAPL 1304(1), which applies to home loans, provides that "at least ninety days before a lender, an assignee or a mortgage loan servicer commences legal action against the borrower . . . including mortgage foreclosure, such lender, assignee or mortgage loan servicer shall give notice to the borrower." The statute sets forth the requirements for the content of such notice, and provides that such notice must be sent by registered or certified mail and by first-class mail to the last known address of the borrower and to the subject residence (see RPAPL 1304[2]). "[P]roper service of RPAPL 1304 notice on the borrower or borrowers is a condition precedent to the commencement of a foreclosure action, and the plaintiff has the burden of establishing satisfaction of this condition" (Aurora Loan Servs., LLC v Weisblum, 85 AD3d at 106; see Citibank, N.A. v Wood, 150 AD3d 813, 814; Flagstar Bank, FSB v Damaro, 145 AD3d 858, 860). By requiring the lender or mortgage loan servicer to send the RPAPL 1304 notice by registered or certified mail and also by first-class mail, " the Legislature implicitly provided the means for the plaintiff to demonstrate its compliance with the statute, i.e., by proof of the requisite mailing,' which can be established with proof of the actual mailings, such as affidavits of mailing or domestic return receipts with attendant signatures, or proof of a standard office mailing procedure designed to ensure that items are properly addressed and mailed, sworn to by someone with personal knowledge of the procedure'" (Bank of Am., N.A. v Bittle, 168 AD3d 656, 658, quoting Wells Fargo Bank, NA v Mandrin, 160 AD3d 1014, 1016). "There is no requirement that a plaintiff in a foreclosure action rely on any particular set of business records to establish a prima facie case, so long as the plaintiff satisfies the admissibility requirements of CPLR 4518(a), and the records themselves actually evince the facts for which they are relied upon" (Citigroup v Kopelowitz, 147 AD3d 1014, 1015). Thus, mailing may be proved by any number of documents meeting the requirements of the business records exception to the hearsay rule under CPLR 4518 (see Viviane Etienne Med. Care, P.C. v Country-Wide Ins. Co., 25 NY3d 498, 508).

Here, the plaintiff's submissions demonstrated, prima facie, that it complied with the mailing requirements of RPAPL 1304 (see HSBC Bank USA N.A. v Ozcan, 154 AD3d 822, 827; HSBC Bank USA, N.A. v Espinal, 137 AD3d 1079, 1080). In opposition, the Skluth defendants submitted an affidavit stating "with absolute certainty" that they never received the 90-day notice either by certified or regular mail. However, a mere denial of receipt—albeit emphatic—is insufficient to raise a triable issue of fact (see Nationstar Mortgage LLC v LaPorte, 162 AD3d 784, 786; HSBC Bank USA N.A. v Ozcan, 154 AD3d at 827). Further, the Skluth defendants acknowledged that they received notices from the plaintiff, which they threw away based upon their attorney's advice that it would be unethical for the plaintiff to serve documents upon them directly. The Skluth defendants also submitted a printout made in 2018 of tracking results from USPS indicating that certain tracking numbers were "not yet in system." Such printouts, where not certified as business records, are not admissible under the business records exception to the hearsay rule (see McBryant v Pisa Holding Corp., 110 AD3d 1034). In any case, it appears those numbers were not in the system because numbers are stored in offline files after 45 days. Therefore, the Skluth defendants failed to raise a triable issue of fact on this issue."

Monday, November 11, 2019

A SALUTE TO...

From the Department of Defense: "Veterans Day is a well-known American holiday, but there are also a few misconceptions about it — like how it’s spelled or whom exactly it celebrates. To clear some of that up, here are the important facts you should know.....https://www.defense.gov/explore/story/article/1675470/5-facts-to-know-about-veterans-day/"

Friday, November 8, 2019

FAILURE TO PAY ADDITIONAL COMPENSATION IS AN IMPROPER DEDUCTION FROM WAGES

ZINNO v. SCHLEHR, 2019 NY Slip Op 6232 - NY: Appellate Div., 4th Dept. 2019:

Plaintiff, a former employee of defendant medical group, commenced this action seeking to recover, inter alia, "additional compensation" that he earned during his employment with defendant. Pursuant to the terms of his employment agreement, plaintiff was entitled to receive an annual salary plus certain "additional compensation" if he exceeded certain thresholds, which were calculated based on the actual gross receipts attributable to plaintiff for services he rendered during his employment with defendant, including receipts received within 90 days following any termination of his employment.

After his employment with defendant terminated, plaintiff became entitled to additional compensation, which defendant was required to pay to plaintiff by June 21, 2016. Although defendant paid plaintiff in part, defendant admitted that it failed to pay plaintiff the entire amount owed for additional compensation. Plaintiff commenced this action asserting, inter alia, a cause of action for violations of Labor Law § 193(1) and alleging that, pursuant to Labor Law § 198(1-a), defendant is liable for the unpaid additional compensation, liquidated damages, interest, and attorneys' fees. Plaintiff moved for partial summary judgment on liability with respect to that cause of action, and Supreme Court denied the motion.

We agree with plaintiff that the court erred in denying his motion with respect to the issue of liability under Labor Law § 193(1), and we therefore modify the order accordingly. There is no dispute that the additional compensation owed to plaintiff constituted earned "wages" that were "vested and mandatory as opposed to discretionary and forfeitable" (Truelove v Northeast Capital & Advisory, 268 AD2d 648, 649 [3d Dept 2000], affd 95 NY2d 220 [2000]; see Labor Law § 190 [1]; see also Doolittle v Nixon Peabody LLP, 126 AD3d 1519, 1520 [4th Dept 2015]), and we conclude that defendant's failure to pay plaintiff by June 21, 2016 the full amount of the additional compensation that plaintiff had earned, as required by the parties' agreement, constituted a deduction from wages in violation of Labor Law § 193(1) (cf. Perella Weinberg Partners LLC v Kramer, 153 AD3d 443, 449-450 [1st Dept 2017]; Miles A. Kletter D.M.D. & Andrew S. Levine, D.D.S., P.C. v Fleming, 32 AD3d 566, 567 [3d Dept 2006]; see generally Doolittle, 126 AD3d at 1522). Thus, plaintiff met his initial burden of establishing "entitlement to judgment as a matter of law" with respect to that part of his motion (Alvarez v Prospect Hosp., 68 NY2d 320, 324 [1986]; see generally Zuckerman v City of New York, 49 NY2d 557, 562 [1980]). Defendant failed to raise material issues of fact whether it violated Labor Law § 193(1) (see generally Jacobsen v New York City Health & Hosps. Corp., 22 NY3d 824, 833 [2014]).

In light of that determination, we further conclude that plaintiff is entitled "to recover the full amount of any underpayment, all reasonable attorney's fees, [and] prejudgment interest" (Labor Law § 198 [1-a]), and we therefore further modify the order accordingly.

Thursday, November 7, 2019

WHEN YOU TERMINATE AN EMPLOYEE - PART 2

Recalling yesterday's post about New York Labor Law Section 195 (6) requiring written notice of termination, etc., it also provided that "Failure to notify an employee of cancellation of accident or health insurance subjects an employer to an additional penalty pursuant to section two hundred seventeen of this chapter." Let us look at that penalty.

New York Labor Law Section 217 (7):

(b) In addition to such penalty, where the failure to comply involves the failure to notify an employee of the termination of a group accident or group health policy pursuant to subdivision three of this section or the failure to remit premiums pursuant to subdivision six of this section, or the failure to provide an individual with notice of termination pursuant to subdivision six of section one hundred ninety-five of this chapter, the policy holder shall also be liable, in a civil action brought by the individual entitled to receive the notice of termination or exercise the right to continuation of coverage in a court of competent jurisdiction, to appropriate damages which shall include reimbursement for medical expenses which were not covered by the policyholder's insurer by virtue of his termination of the policy or failure to remit such premiums."

And this is in addition to the penalties under New York Labor Law Section 218 (1) which state, in effect, that an employer who violates the non-monetary provisions of Article 6 of the Labor Law (which includes Section 195), is subject to a maximum penalty of $1,000 for a first violation, $2,000 for a second violation and $3,000 for a third or subsequent violation.

Wednesday, November 6, 2019

WHEN YOU TERMINATE AN EMPLOYEE - PART 1

A written notice is required.

New York Labor Law Section 195 provides:

"Every employer shall:

6. notify any employee terminated from employment, in writing, of the exact date of such termination as well as the exact date of cancellation of employee benefits connected with such termination. In no case shall notice of such termination be provided more than five working days after the date of such termination. Failure to notify an employee of cancellation of accident or health insurance subjects an employer to an additional penalty pursuant to section two hundred seventeen of this chapter."

Tuesday, November 5, 2019

IF YOU WORK, YOU STILL GET TIME TO VOTE

NYS Election Law 3-110

1. A registered voter may, without loss of pay for up to three hours, take off so much working time as will enable him or her to vote at any election.

2. The employee shall be allowed time off for voting only at the beginning or end of his or her working shift, as the employer may designate, unless otherwise mutually agreed.

3. If the employee requires working time off to vote the employee shall notify his or her employer not less than two working days before the day of the election that he or she requires time off to vote in accordance with the provisions of this section.

4. Not less than ten working days before every election, every employer shall post conspicuously in the place of work where it can be seen as employees come or go to their place of work, a notice setting forth the provisions of this section. Such notice shall be kept posted until the close of the polls on election day.

Monday, November 4, 2019

FREE MORTGAGE FORECLOSURE CLINIC TODAY

All clinics are 3-6 p.m. and are held at the Nassau County Bar Association in Mineola twice a month. Call to make an appointment for the next scheduled clinic.

→Please call NCBA for the scheduled dates for Free Legal Consultation

Friday, November 1, 2019

ETHICS IN LAW - REPORTING PROFESSIONAL MISCONDUCT

In the New York Rules of Professional Conduct, Rule 8.3 provides, in pertinent part:

"(a) A lawyer who knows that another lawyer has committed a violation of the Rules of Professional Conduct that raises a substantial question as to that lawyer's honesty, trustworthiness or fitness as a lawyer shall report such knowledge to a tribunal or other authority empowered to investigate or act upon such violation.

* * * * *

(c) This Rule does not require disclosure of: (1) information otherwise protected by Rule 1.6; or (2) information gained by a lawyer or judge while participating in a bona fide lawyer assistance program."

For example, and according to New York State Bar Association Committee on Professional Ethics Opinion #854 (03/11/2011), if Lawyer A was employed formerly by Lawyer P and knew of wrongful conduct:

"12. Lawyer A must report the conduct of his former employer, Lawyer P, to an appropriate authority if all four of the following criteria are met: (1) Lawyer A has knowledge or a clear belief concerning the pertinent facts (i.e., he has more than a reasonable belief or mere suspicion); (2) Lawyer A's report will not reveal confidential information protected by Rule 1.6 or information that Lawyer A gained while participating in a bona fide lawyer assistance program; (3) the conduct by Lawyer P constitutes a violation of one or more Rules of Professional Conduct; and (4) the violation raises a substantial question as to Lawyer P's honesty, trustworthiness or fitness as a lawyer.

13. If all four of those criteria are met, Lawyer A may also report such misconduct to the affected clients of Lawyer P - but before informing the clients, Lawyer A should carefully weigh both dangers to Lawyer P's attorney-client relationships if the affected clients are informed against the countervailing dangers to the clients if they are not informed.

14. Even if Lawyer A is not satisfied that all four criteria have been met, Lawyer A may nevertheless report a good faith belief or suspicion of Lawyer P's alleged misconduct to an appropriate authority, provided that the report of the suspected misconduct does not require the disclosure of confidential information or information that Lawyer A gained while participating in a bona fide lawyer assistance program. But Lawyer A may not inform Lawyer P's clients about mere suspicions of Lawyer P's misconduct."