Thursday, February 28, 2019

Wednesday, February 27, 2019

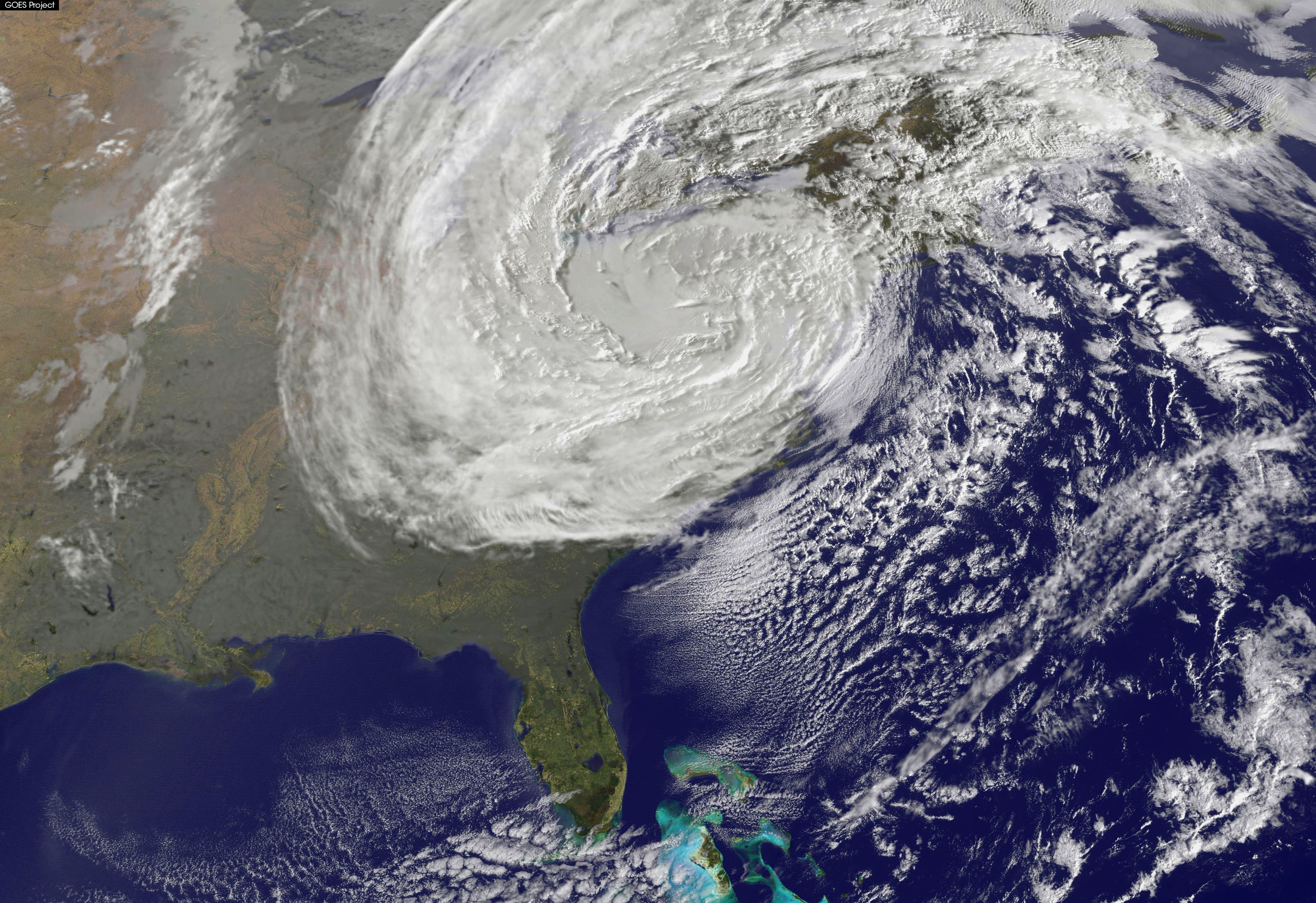

A SANDY ISSUE - COVERAGE UNDER INSURANCE

6 1/2 years after Superstorm Sandy and litigations still exist; in this matter, a new trial was ordered.

Greenberg v Privilege Underwriters Reciprocal Exch., 2019 NY Slip Op 01202, Decided on February 20, 2019, Appellate Division, Second Department:

"The plaintiffs' home, located in the Bergen Beach area of Brooklyn, was damaged in late October 2012 during Hurricane Sandy. The plaintiffs' basement was flooded and, according to the plaintiffs, other areas of the home also sustained water damage. The plaintiffs' homeowners' insurance policy, issued by the defendant, insured against "all risks of sudden and accidental direct physical loss or damage to [the] dwelling . . . unless an exclusion applies." The policy provided additional coverage for loss or damage caused by "[w]ater which backs up through sewers or drains," or "[w]ater which overflows from a sump even if such overflow results from the mechanical breakdown of the sump pump." However, the policy excluded from coverage "any loss by surface or ground water," defined as "[f]lood, surface water, waves, tidal water, overflow of a body of water, or spray from any of these, whether or not driven by wind."

The plaintiffs commenced this action, inter alia, to recover damages for the defendant's alleged breach of the policy for failing to provide coverage for the damage to their home. At trial, the primary issue was whether the water damage to the plaintiffs' home was covered or excluded by the policy. The plaintiffs presented evidence that the flooding of the basement and water damage to the other areas of their home resulted from a pressurized back up of the sewer system. In contrast, the defendant presented evidence that the flooding of the basement and other claimed losses were caused by groundwater and tidal flooding.

Over the defendant's objection, the Supreme Court instructed the jury that if the [*2]plaintiffs' home "was damaged by two or more conditions or events, any one of which is covered under the insurance policy . . . then [the defendant] may be liable if . . . the conditions or events acted together to cause the damage to the [plaintiffs'] home." The jury returned a verdict in favor of the plaintiffs and against the defendant, awarding damages in the principal sum of $1,875,386.92. The defendant appeals. We reverse and grant a new trial.

"A trial court is required to state the law relevant to the particular facts in issue, and a set of instructions that confuses or incompletely conveys the germane legal principles to be applied in a case requires a new trial" (J.R. Loftus, Inc. v White, 85 NY2d 874, 876). Under an all-risk property damage policy, where multiple perils work together to cause the same loss, and one or more of those perils is covered under the policy, New York follows the majority rule such that the loss will be covered if the "proximate, efficient and dominant cause" of the loss is covered by the policy (Album Realty Corp. v American Home Assur. Co., 80 NY2d 1008, 1010; see Neuman v United Servs. Auto. Assn., 74 AD3d 925, 926; Kannatt v Valley Forge Ins. Co., 228 AD2d 564, 564-565; see also 5 New Appleman on Insurance Law Library Edition § 44.03[5] [2018]). By contrast, a minority of jurisdictions adhere to the broader "concurrent cause" rule, under which a loss will be covered "if any one of multiple non-remote causes of the same loss is a non-excluded peril" (5 New Appleman on Insurance Law Library Edition § 44.03[3] [2018]).

Here, the Supreme Court's instruction to the jury misstated the law in that it permitted the jury to find coverage for the plaintiffs' loss if one or more covered perils acted together with a noncovered peril to cause the same loss, without regard to whether the efficient or dominant cause of the loss was a covered peril under the policy. Since the error may have prejudiced the defendant, a new trial is warranted (see Rakoff v New York City Dept. of Educ., 110 AD3d 780, 781; see also J.R. Loftus, Inc. v White, 85 NY2d at 876; Moore v New York El. R.R. Co., 130 NY 523, 529). The Supreme Court's instruction to the jury, in effect, that the exclusion for losses caused by surface or ground water was ambiguous, was also erroneous (see Platek v Town of Hamburg, 24 NY3d 688, 697; see also White v Continental Cas. Co., 9 NY3d 264, 267; Cali v Merrimack Mut. Fire Ins. Co., 43 AD3d 415, 417).

We agree with the Supreme Court's determination to permit one of the plaintiffs' expert witnesses to testify regarding the necessity and reasonable costs associated with demolishing and rebuilding of the plaintiffs' home (see De Long v County of Erie, 60 NY2d 296, 307; Felicia v Boro Crescent Corp., 105 AD3d 697, 698; Formica v Formica, 101 AD3d 805, 806)."

Tuesday, February 26, 2019

ISSUES WITH FORECLOSURE RESCUE FIRM

Ramirez v Donado Law Firm, P.C., 2019 NY Slip Op 01244, Decided on February 20, 2019, Appellate Division, Second Department:

"The plaintiffs allegedly were the victims of a foreclosure rescue scam perpetrated by the defendants Donado Law Firm, P.C. (hereinafter Donado Law), Valmiro Donado, and Roberto Pagan-Lopez (hereinafter collectively the defendants), among others. The plaintiffs commenced this action alleging, inter alia, violations of Real Property Law § 265-b and General Business Law § 349, as well as fraud, fraudulent inducement, fraudulent misrepresentation, breach of contract, and legal malpractice. The defendants moved pursuant to CPLR 3211(a)(7) to dismiss the complaint insofar as asserted against them. The Supreme Court, inter alia, denied the motion, and the defendants appeal.

A party may move for judgment dismissing one or more causes of action on the ground that the pleading fails to state a cause of action (see CPLR 3211[a][7]). On a motion to dismiss pursuant to CPLR 3211(a)(7), the pleading must be afforded a liberal construction and the court must "accept the facts as alleged in the complaint as true, accord plaintiffs the benefit of every possible favorable inference, and determine only whether the facts as alleged fit within any cognizable legal theory" (Leon v Martinez, 84 NY2d 83, 87-88; see Stone v Bloomberg L.P., 163 AD3d 1028; Rodriguez v Daily News, L.P., 142 AD3d 1062, 1063). "Where evidentiary material is submitted and considered, and the motion is not converted into a motion for summary judgment, the question becomes whether the plaintiff has a cause of action, not whether the plaintiff has stated one, and unless it has been shown that a material fact as claimed by the plaintiff to be one is not a fact at all and it cannot be said that a significant dispute exists regarding it, dismissal should not eventuate" (Stone v Bloomberg L.P., 163 AD3d at 1030; see Guggenheimer v Ginzburg, 43 NY2d [*2]268, 275; Rodriguez v Daily News, L.P., 142 AD3d at 1063).

Real Property Law § 265-b governs the conduct of distressed property consultants. "Distressed property consultant" or "consultant" is defined as "an individual or a corporation, partnership, limited liability company or other business entity that, directly or indirectly, solicits or undertakes employment to provide consulting services to a homeowner for compensation or promise of compensation with respect to a distressed home loan or a potential loss of the home for nonpayment of taxes" (Real Property Law § 265-b[1][e]). A consultant does not include, inter alia, "an attorney admitted to practice in the state of New York when the attorney is directly providing consulting services to a homeowner in the course of his or her regular legal practice" (Real Property Law § 265-b(1)(e)[i]). Here, contrary to the defendants' contention, the plaintiffs adequately alleged facts from which it could be inferred that the defendants did not provide consulting services to the plaintiffs in the course of Donado Law's regular legal practice (see De Guaman v American Hope Group, 163 AD3d 915). Accordingly, we agree with the Supreme Court's denial of that branch of the defendants' motion which was pursuant to CPLR 3211(a)(7) to dismiss the cause of action alleging a violation of Real Property Law § 265-b insofar as asserted against them.

General Business Law § 349(a) prohibits "[d]eceptive acts or practices in the conduct of any business, trade or commerce or in the furnishing of any service in this state." A cause of action to recover damages for a violation of General Business Law § 349 must "identify consumer-oriented misconduct which is deceptive and materially misleading to a reasonable consumer, and which causes actual damages" (Wilner v Allstate Ins. Co., 71 AD3d 155, 161-162; see Oswego Laborers' Local 214 Pension Fund v Marine Midland Bank, 85 NY2d 20, 25). Private contract disputes, unique to the parties, do not fall within the ambit of General Business Law § 349 (see Oswego Laborers' Local 214 Pension Fund v Marine Midland Bank, 85 NY2d at 25; De Guaman v American Hope Group, 163 AD3d at 917). Here, contrary to the defendants' contention, "in contrast to a private contract dispute, the practices alleged by the plaintiffs were not unique to these parties and involved an extensive marketing scheme that had a broader impact on consumers at large" (De Guaman v American Hope Group, 163 AD3d at 917 [citations and internal quotation marks omitted]; see Gaidon v Guardian Life Ins. Co. of Am., 94 NY2d 330, 344; Oswego Laborers' Local 214 Pension Fund v Marine Midland Bank, 85 NY2d at 25). Accordingly, we agree with the Supreme Court's denial of that branch of the defendants' motion which was pursuant to CPLR 3211(a)(7) to dismiss the cause of action alleging a violation of General Business Law § 349 insofar as asserted against them.

"Where a cause of action or defense is based upon misrepresentation, fraud, mistake, wilful default, breach of trust or undue influence, the circumstances constituting the wrong shall be stated in detail" (CPLR 3016[b]). However, the requirements of CPLR 3016(b) " may be met when the facts are sufficient to permit a reasonable inference of the alleged conduct'" (Sargiss v Magarelli, 12 NY3d 527, 531, quoting Pludeman v Northern Leasing Sys., Inc., 10 NY3d 486, 492). Here, contrary to the defendants' contention, the complaint pleaded causes of action sounding in fraud, fraudulent inducement, and fraudulent misrepresentation with sufficient particularity (see CPLR 3016; Sargiss v Magarelli, 12 NY3d at 531; Pludeman v Northern Leasing Sys., Inc., 10 NY3d at 492; De Guaman v American Hope Group, 163 AD3d at 917). Moreover, contrary to the defendants' contention, the causes of action sounding in fraud, fraudulent inducement, and fraudulent misrepresentation were not duplicative of the breach of contract cause of action (see De Guaman v American Hope Group, 163 AD3d at 917; see also Neckles Bldrs., Inc. v Turner, 117 AD3d 923, 925). Accordingly, we agree with the Supreme Court's denial of that branch of the defendants' motion which was pursuant to CPLR 3211(a)(7) to dismiss the causes of action sounding in fraud, fraudulent inducement, and fraudulent misrepresentation insofar as asserted against them.

"To recover damages for breach of contract, plaintiffs must demonstrate the existence of a contract, [their] performance pursuant to that contract, the defendants' breach of their obligations pursuant to the contract, and damages resulting from that breach'" (De Guaman v American Hope Group, 163 AD3d at 917, quoting Elisa Dreier Reporting Corp. v Global NAPs Networks, Inc., 84 AD3d 122, 127). Here, contrary to the defendants' contention, the plaintiffs sufficiently pleaded a cause of action alleging breach of contract (see De Guaman v American Hope [*3]Group, 163 AD3d at 917). Accordingly, we agree with the Supreme Court's denial of that branch of the defendants' motion which was pursuant to CPLR 3211(a)(7) to dismiss the cause of action sounding in breach of contract insofar as asserted against them.

To recover damages for legal malpractice, a plaintiff must establish "that the attorney failed to exercise the ordinary reasonable skill and knowledge commonly possessed by a member of the legal profession and that the attorney's breach of this duty proximately caused plaintiff to sustain actual and ascertainable damages" (Dombrowski v Bulson, 19 NY3d 347, 350 [internal quotation marks omitted]; see Rudolf v Shayne, Dachs, Stanisci, Corker & Sauer, 8 NY3d 438, 442; Dempster v Liotti, 86 AD3d 169, 176). "To establish causation, a plaintiff must show that he or she would have prevailed in the underlying action or would not have incurred any damages, but for the lawyer's negligence" (Rudolf v Shayne, Dachs, Stanisci, Corker & Sauer, 8 NY3d at 442; see Garcia v Polsky, Shouldice & Rosen, P.C., 161 AD3d 828, 830; Kliger-Weiss Infosystems, Inc. v Ruskin Moscou Faltischek, P.C., 159 AD3d 683, 684). Here, contrary to the defendants' contention, the complaint sufficiently pleaded a cause of action to recover damages for legal malpractice (see Garcia v Polsky, Shouldice & Rosen, P.C., 161 AD3d at 830; Hershco v Gordon & Gordon, 155 AD3d 1007, 1009). Accordingly, we agree with the Supreme Court's denial of that branch of the defendants' motion which was pursuant to CPLR 3211(a)(7) to dismiss the cause of action sounding in legal malpractice insofar as asserted against them."

Monday, February 25, 2019

MORE ON SOCIAL MEDIA DISCOVERY

I read about this case in last weeks NYLJ. Social Media can be discoverable with reasonable limitations.

Vasquez-Santos v Mathew, 2019 NY Slip Op 00541, Decided on January 24, 2019, Appellate Division, First Department:

"Order, Supreme Court, New York County (Adam Silvera, J.), entered June 7, 2018, which, to the extent appealed from as limited by the briefs, denied defendant's motion to compel access by a third-party data mining company to plaintiff's devices, email accounts, and social media accounts, so as to obtain photographs and other evidence of plaintiff engaging in physical activities, unanimously reversed, on the law and the facts, without costs, and the motion granted to the extent indicated herein.

Private social media information can be discoverable to the extent it "contradicts or conflicts with [a] plaintiff's alleged restrictions, disabilities, and losses, and other claims" (Patterson v Turner Const. Co., 88 AD3d 617, 618 [1st Dept 2011]). Here, plaintiff, who at one time was a semi-professional basketball player, claims that he has become disabled as the result of the automobile accident at issue, such that he can no longer play basketball. Although plaintiff testified that pictures depicting him playing basketball, which were posted on social media after the accident, were in games played before the accident, defendant is entitled to discovery to rebut such claims and defend against plaintiff's claims of injury. That plaintiff did not take the pictures himself is of no import. He was "tagged," thus allowing him access to them, and others were sent to his phone. Plaintiff's response to prior court orders, which consisted of a HIPAA authorization refused by Facebook, some obviously immaterial postings, and a vague affidavit claiming to no longer have the photographs, did not comply with his discovery obligations. The access to plaintiff's accounts and devices, however, is appropriately limited in time, i.e., only those items posted or sent after the accident, and in subject matter, i.e., those items discussing or showing defendant engaging in basketball or other similar physical activities (see Forman v Henkin, 30 NY3d 656, 665 [2018]; see also Abdur-Rahman v Pollari, 107 AD3d 452, 454 [1st Dept 2013])."

Labels:

Discovery,

LITIGATION,

Social Media

Friday, February 22, 2019

MORTGAGE FORECLOSURE: STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS DEFENSE NOT AVAILABLE

Wells Fargo Bank v. Rodriguez, NYLJ 2/21/19, Date filed: 2019-01-25, Court: Supreme Court, Queens, Judge: Justice Denis Butler, Case Number: 716731/2017:

"The initial date of default upon the loan was February 1, 2010. Borrower argues that the note was accelerated on September 8, 2010, by operation of the acceleration letter mailed to him on August 6, 2010, and his failure to cure. A prior foreclosure action was commenced but discontinued, on consent, on May 25, 2016. Borrower now moves the dismiss the complaint as time-barred (see CPLR 213 [3]; 3211 [a] [5]), arguing that the lender made no overt act of revocation and that the voluntary discontinuance did not decelerate the note because the acceleration was not accomplished by commencement of the prior action.

An action to foreclose a mortgage is subject to a six-year statute of limitations (see CPLR 213 [4]). That limitations period begins to run on the entire debt when the mortgagee elects to accelerate the mortgage (see U.S. Bank, N.A. v. Martin, 144 AD3d 891, 891-892 [2d Dept 2016]; EMC Mtge. Corp. v. Smith, 18 AD3d 602 [2d Dept 2005]; Loiacono v. Goldberg, 240 AD2d 476, 477 [2d Dept 1997]). “Acceleration occurs, inter alia, by the commencement of a foreclosure action” (Deutsche Bank Natl. Trust Co. v. Adrian, 157 AD3d 934, 935 [2d Dept 2018]; see Fannie Mae v. 133 Mgt., LLC, 126 AD3d 670, 670 [2d Dept 2015]; Clayton Natl. v. Guldi, 307 AD2d 982, 982 [2d Dept 2003]). “A lender may revoke its election to accelerate the mortgage, but it must do so by an affirmative act of revocation occurring during the six-year statute of limitations period subsequent to the initiation of the prior foreclosure action” (NMNT Realty Corp. v. Knoxville 2012 Trust, 151 AD3d 1068,1069-1070 [2d Dept 2017]). The Court of Appeals has held that when there is a validly filed stipulation of discontinuance resolving a case, it is as if the case “had never been begun” (Yonkers Fur Dressing Co. Inc. v. Royal Ins. Co. Ltd., 247 NY 435, 444, 160 N.E. 778 [1928]). In Housberg v. Baker (146 Misc 2d 960, 962 [Sup Ct, Suffolk County 1990], quoting treatise on New York law, the court stated as follows:

“When an action is discontinued, it is as if the action had never been; all prior orders in the case are nullified. Once an action has been discontinued, there can be no judgment or appeal, and no objection to another action for the same relief on the ground that a prior action is pending…once an action has been discontinued by consent or stipulation, it is [as though] the action never existed….”

The Second Department has adhered to that rule. In Newman v. Newman (245 AD2d 353, 354 [2d Dept 1997]), the court held that “[w]hen an action is discontinued, it is as if it had never been; everything done in the action is annulled and all prior orders in the case are nullified.” Furthermore, in U.S. Bank N.A. v. Wongsonadi (55 Misc 3d 1207[A], 2017 NY Slip Op 50452[U] [Sup Ct, Queens County 2017]), the court noted that “the election to accelerate contained in the complaint was nullified when plaintiff voluntarily discontinued the prior action” and the discontinuance of the prior foreclosure action was therefore “an affirmative act of revocation.”

This court declines to extend the ruling in cases such as EMC Mortg. Corp. v. Patella (279 AD2d 604 [2d Dept 2001]) and Federal National Mortgage Association v. Mebane (208 [*2]AD2d 892 [2d Dept 1994]). In Patella, the initial foreclosure action was dismissed by the court because the lender failed to appear at a certification conference. Similarly, in Mebane, ” [t]he prior foreclosure action was never withdrawn by the lender, but rather, dismissed sua sponte by the court” (208 AD2d at 894). The rule to extrapolate is that, unlike a voluntary discontinuance, a dismissal by the court does not constitute an affirmative act by the lender to revoke its election to accelerate (see e.g. MSMJ Realty, LLC v. DLJ Mortg. Capital, Inc., 157 AD3d 885 [2d Dept 2018] [finding that the statute of limitations had run where the first foreclosure action was dismissed sua sponte for lack of personal jurisdiction]; Kashipour v. Wilmington Sav. Fund Socy., FSB, 144 AD3d 985, 986 [2d Dept 2016] [holding that the statute of limitations had run where the first foreclosure action was dismissed without prejudice for failure to comply with the notice requirements of RPAPL 1303]).

Here, even if the debt was accelerated on September 8, 2010, which the court does not find, the prior action was voluntarily discontinued within six years of that date (cf. Deutsche Bank Natl. Trust Co. v. Adrian, 157 AD3d 934, 935-936), and the election to accelerate the debt was thereby revoked by affirmative act. It is immaterial whether an acceleration is effected by letter or commencement of a foreclosure action. A voluntary discontinuance is an affirmative act that functions to decelerate the debt.

Moreover, pursuant to section 19 of the mortgage, plaintiff bargained away its right to demand payment in full simply upon a default in an installment payment or the commencement of an action and has afforded borrower greater protections than that set forth in the statutory form of an acceleration clause under Real Property Law §258 or under the holding in Albertina Realty Co. v. Rosbro Realty Corp. (258 NY 472 [1932]). “A familiar and eminently sensible proposition of law, is that, when parties set down their agreement in a clear, complete document, their writing should as a rule be enforced according to its terms” (W.W.W. Assocs. v. Giancontieri, 77 NY2d 157 [1990]). “As with any other contractual option, the holder of an option may be required to exercise an option to accelerate the maturity of a loan in accordance with the terms of the mortgage” (Nationstar Mortg., LLC v. MacPherson, 56 Misc 3d 339, 350 [Sup Ct, Suffolk County 2017]).

Under the express wording the mortgage document, section 19, plaintiff has no right to reject borrower’s payment of arrears in order to reinstate the mortgage, until a judgment is entered. Under the contract terms at issue, plaintiff does not have a legal right to require payment in full by filing a foreclosure action or sending an acceleration letter. Borrower could pay the unpaid installments and the payment of same would destroy the option to accelerate. Until the option to declare the entire debt due is effectively exercised, borrower has the right to tender the payments then due and make good on his or her defaults. Here, it is a judgment that triggers the acceleration in full of the entire mortgage debt.

Contrary to borrower’s contentions, the instant foreclosure action is not time-barred (see CPLR 213 [4]). Accordingly, borrower’s motion to dismiss the complaint is denied."

Thursday, February 21, 2019

PAYING RENT LATE FOR HABITUAL BREACH OF WARRANTABILITY

The tenants here did not owe any rent, only late fees--charged 31 of 34 times they paid rent late. And they did this intentionally to prod the landlord to get work done as the wood floor sagged, the bathroom was never properly fixed after the ceiling collapsed, and there was water damage and mold.

156 E. 37th St. LLC v. Eichner, NYLJ 2/20/19, Date filed: 2019-02-06, Court: Civil Court, New York, Judge: Judge Jack Stoller, Case Number: 63915/2018:

"New York State implies into every residential lease a warranty that the demised premises are habitable, RPL §235-b(1), and any purported modification of this warranty is void as a matter of public policy. RPL §235-b(2). “The only meaningful weapon a tenant has against a landlord for refusing to maintain the premises in a habitable condition is to withhold rent.” Semans Family Ltd. Pshp. v. Kennedy, 177 Misc 2d 345, 348 (Civ. Ct. NY Co. 1998), citing 520 E. 86th St., Inc. v. Leventritt, 127 Misc 2d 566, 570 (Civ. Ct. NY Co. 1985)(Saxe, J.). See Ansonia Assocs. v. Ansonia Residents’ Asso., 78 AD2d 211, 220 (1st Dept. 1980)(referring, in dicta, to a “right” to withhold rent), Whitby Operating Corp. v. Schleissner, 117 Misc 2d 794, 800 (S. Ct. NY Co. 1982).1 Respondents proved the persistence of ongoing conditions in the subject premises in need of repair, which Petitioner’s own rebuttal witness essentially corroborated, and Respondents proved, particularly by their unrebutted letters in evidence, that they intended to prompt Petitioner to repair the conditions by withholding rent, even if they eventually paid the monthly rent before Petitioner could commence a nonpayment proceeding.

A warranty of habitability defense implicates a “clear public policy interest.” Windy Acres Farm, Inc. v. Penepent, 40 Misc 3d 63, 64-65 (App. Term 2nd Dept. 2013). To the extent that terms of a landlord/tenant relationship impair the ability of a tenant to withhold rent, then, such terms impermissibly modify the statutory warranty of habitability, as follows:

The New York City Housing Authority may not administratively penalize a tenant who withholds rent to enforce the warranty of habitability. Law v. Franco, 180 Misc 2d 737 (S. Ct. Bronx Co. 1999);

While a landlord otherwise has a cause of action for a judgment against a tenant when a tenant’s nonpayment of rent compels the landlord to commence an excessive number of nonpayment proceedings, Adams Tower L.P. v. Richter, 186 Misc 2d 620, 621-22 (App. Term 1st Dept. 2000), bona fide habitability defenses that caused a tenant to withhold rent preclude an eviction on that ground. Chama Holding Corp. v. Taylor, 37 Misc 3d 70, 71 (App. Term 1st Dept. 2012), Hudson St. Equities v. Circhi, 9 Misc 3d 138(A)(App. Term 1st Dept. 2005), citing Bennett v. Mantis, N.Y.L.J., Sept. 13, 2000, at 22:1 (App. Term 1st Dept.), 31-67 Astoria Corp. v. Cabezas, 55 Misc 3d 132(A) (App. Term 2nd Dept. 2017), Time Equities Assocs. LLC v. McKenith, 2019 NY Slip Op. 50123(U), 4 (Civ. Ct. NY Co.), Wonforo Assocs. v. Maloof, 2002 NY Slip Op. 50316(U), 11 (Civ. Ct. NY Co.);

A conditional limitation providing for the forfeiture of a tenancy upon nonpayment of rent is void as against public policy as it deprives tenants of their right to interpose a breach of warranty of habitability claim. Windy Acres Farm, Inc., supra, 40 Misc 3d at 64-65, Reinozo v. Eskander, 2017 N.Y.L.J. LEXIS 2151, *4 (Civ. Ct. Queens Co.);

A landlord may not invoke a lease rider forfeiting a rent credit on nonpayment where the tenant has asserted a good-faith claim of breach of the warranty of habitability. 1461 Amsterdam Ave. LLC v. Carrasquillo, 2015 NY Slip Op. 30831(U), 3 (Civ. Ct. NY Co.);

A landlord may not maintain a holdover eviction proceeding on no alleged cause against an unregulated tenant in retaliation for the tenant withholding the rent to enforce the tenant’s “rights under the warranty of habitability….” Barr v. Huggins, 41 Misc 3d 605, 613 (Civ. Ct. Bronx Co. 2013).

A late fee clause in a lease does not per se offend public policy, and may give rise to a cause of action for a money judgment in a summary proceeding, Brusco v. Miller, 167 Misc 2d 54, 55-56 (App. Term 1st Dept. 1995), as Petitioner seeks herein. However, as applied in this matter, the late fee would penalize Respondents as Respondents withheld rent over repairs. Petitioner’s application of the late fees to these particular facts would therefore impermissibly modify the warranty of habitability just as readily as a conditional limitation or a lease rider forfeiting a rent credit would. Accordingly, the Court finds that the late fee clause, as applied herein, is unenforceable as a matter of public policy.

A separate ground for rendering purported late fees unenforceable is that 5 percent per month, or 60 percent per year, amounts to an excessive and usurious charge. Cleo Realty Assocs., L.P. v. Papagiannakis, 151 AD3d 418, 419 (1st Dept. 2017).

Finally, although Petitioner charged a monthly rent at a so-called “holdover rate” after the expiration of Respondents’ most recent lease and before Respondents vacated, the lease in evidence does not entitle Petitioner to that relief.

Without the late fees and the holdover rate, Respondents do not owe anything to Petitioner. The Court therefore dismisses this proceeding with prejudice."

Labels:

Fees,

Landlord Tenant Law,

Rent,

Warranty of Habitability

Wednesday, February 20, 2019

DISPUTE OVER ATTORNEY FEES FOR A DISCHARGED ATTORNEY IN DIVORCE

Sometimes, the attorney/client relationship breaks down just like the marital relationship.

Rhodes v Rhodes, 2019 NY Slip Op 01113, Decided on February 13, 2019, Appellate Division, Second Department:

"The plaintiff and the defendant were married in 1993 and have three children. The parties divorced in 2008. In 2013, the defendant moved to modify the parties' custody arrangement so as to award him residential custody of the children. In an order dated December 22, 2014, the Supreme Court awarded the defendant residential custody of the children and awarded the plaintiff parental access. The plaintiff appealed from that order.

In May 2015, the plaintiff moved for interim appellate attorney's fees and costs. In an order dated August 25, 2015 (hereinafter the August 2015 order), the Supreme Court, in effect, granted the plaintiff's motion, awarding her a total of $20,000 in attorney's fees and costs "for the prosecution of the appeal, with leave to apply for additional sums upon the completion of the [*2]appeal." The defendant was to pay those attorney's fees and costs to the plaintiff's then-attorney, the nonparty, Karyn A. Villar, PLLC (hereinafter the Villar firm), within 20 days of the order.

On September 23, 2015, the Villar firm moved to hold the defendant in civil contempt of the August 2015 order. The defendant cross-moved for leave to renew his opposition to the plaintiff's prior motion for interim appellate attorney's fees and costs. The defendant attached to his cross motion, inter alia, a stipulation of settlement dated September 28, 2015, wherein the plaintiff and the defendant agreed that the plaintiff would waive payment of attorney's fees and costs owed by the defendant pursuant to the August 2015 order. The plaintiff retained new counsel, and thereafter cross-moved to impose sanctions against the Villar firm, arguing that the Villar firm's contempt motion was punitive and an abuse of process.

In an order dated March 7, 2016, the Supreme Court (1) denied the Villar firm's motion to hold the defendant in civil contempt, (2) granted the defendant's cross motion for leave to renew and, upon renewal, in effect, vacated the August 2015 order granting the plaintiff's motion for interim appellate attorney's fees and costs, and thereupon denied the plaintiff's motion, and (3) granted the plaintiff's cross motion to impose sanctions against the Villar firm, and directed the Villar firm to pay the plaintiff's attorney's fees in the sum of $2,500. The Villar firm appeals.

The Supreme Court should have granted the Villar firm's motion to hold the defendant in civil contempt. To prevail on a motion to hold another party in civil contempt, the movant is "required to prove by clear and convincing evidence (1) that a lawful order of the court, clearly expressing an unequivocal mandate, was in effect, (2) that the order was disobeyed and the party disobeying the order had knowledge of its terms, and (3) that the movant was prejudiced by the offending conduct" (El-Dehdan v El-Dehdan, 114 AD3d 4, 16 [internal quotation marks omitted]; see Matter of Philie v Singer, 79 AD3d 1041, 1042). The movant in a civil contempt proceeding need not establish "that the disobedience [was] deliberate or willful" (Matter of Philie v Singer, 79 AD3d at 1042). "Once the movant establishes a knowing failure to comply with a clear and unequivocal mandate, the burden shifts to the alleged contemnor to refute the movant's showing, or to offer evidence of a defense, such as an inability to comply with the order" (El-Dehdan v El-Dehdan, 114 AD3d at 17).

Here, the defendant disputes the Villar firm's showing only as to the first and third prongs of El-Dehdan v El-Dehdan (114 AD3d at 16). As to the first prong, the Villar firm established "that a lawful order of the court, clearly expressing an unequivocal mandate, was in effect" (id. at 16), by attaching the August 25, 2015, order to the contempt motion, which order unequivocally directed the defendant to pay the Villar firm $20,000 in interim appellate attorney's fees and costs within 20 days of the order. As noted, it is undisputed that the defendant had knowledge of the terms of the August 25, 2015, order and that he did not comply with them. Finally, as to the third prong, the Villar firm demonstrated that it had begun drafting the plaintiff's appellate brief and that it was owed compensation for legal services that were performed before the Villar firm was discharged.

The defendant's proffered defenses in response to the Villar firm's showing were without merit. The plaintiff's subsequent decision to waive attorney's fees and to discharge the Villar firm did not preclude the Villar firm from collecting fees that it incurred before it was discharged, so long as it was discharged without cause (see Frankel v Frankel, 2 NY3d 601, 606-607; Matter of Gregory v Gregory, 109 AD3d 616, 617). The defendant did not contend or establish in his opposition papers that the plaintiff discharged the Villar firm for cause. Furthermore, the Villar firm was not required to exhaust other enforcement remedies before seeking to hold the defendant in civil contempt (see L 2016, ch 365, §§ 1, 2; Cassarino v Cassarino, 149 AD3d 689, 691). Under the circumstances, the Supreme Court should have granted the Villar firm's motion to hold the defendant in civil contempt (see generally El-Dehdan v El-Dehdan, 114 AD3d at 16).

Although the Supreme Court had awarded the Villar firm a total of $20,000 for the prosecution of the plaintiff's appeal, the record demonstrates that the plaintiff discharged the Villar firm before the appeal was completed. Accordingly, under the circumstances, we remit the matter [*3]to the Supreme Court, Suffolk County, to determine the amount of the attorney's fees and costs that the Villar firm is owed by the defendant, taking into consideration factors such as when the plaintiff directed the Villar firm to stop working on the appeal, when the plaintiff discharged the Villar firm, "the complexity of the issues involved, and the reasonableness of counsel's performance and the fees under the circumstances" (Matter of Gregory v Gregory, 109 AD3d at 618 [internal quotation marks omitted]).

We disagree with the Supreme Court's determination granting the defendant leave to renew his opposition to the plaintiff's prior motion for interim appellate attorney's fees and costs. Before the parties settled their underlying custody dispute and discontinued the appeal from the order dated December 22, 2014, the Villar firm performed work on, and incurred expenses arising from, the appeal from that order. As discussed above, the Villar firm was entitled to payment for its work despite the parties' settlement and attempt to waive attorney's fees and costs. Thus, the settlement and withdrawal of that appeal did not constitute new facts "that would change the prior determination," and the court should have denied the defendant's cross motion for leave to renew (CPLR 2221[e][2]).

We also disagree with the Supreme Court's determination granting the plaintiff's cross motion to impose sanctions against the Villar firm for pursuing the contempt motion. Contrary to the Villar firm's contention, the court did not violate its rights in deciding the motion without a hearing, as the plaintiff expressly requested the subject relief in her motion papers, and the Villar firm was afforded an opportunity to be heard and to oppose the motion (see Matter of Ruth S. [Sharon S.], 125 AD3d 978, 980; see e.g. Levine v Levine, 111 AD3d 898, 899). However, the Villar firm is correct that sanctions were not warranted in this case. "In addition to or in lieu of awarding costs, the court, in its discretion may impose financial sanctions upon any party or attorney in a civil action or proceeding who engages in frivolous conduct" (22 NYCRR 130-1.1[a]; see Weissman v Weissman, 116 AD3d 848, 849). "[C]onduct is frivolous if . . . (1) it is completely without merit in law and cannot be supported by a reasonable argument for an extension, modification or reversal of existing law; (2) it is undertaken primarily to delay or prolong the resolution of the litigation, or to harass or maliciously injure another; or (3) it asserts material factual statements that are false" (22 NYCRR 130-1.1[c]; see Weissman v Weissman, 116 AD3d at 849). Contrary to the Supreme Court's determination, there is no evidence in the record to support a finding that the Villar firm pursued the contempt motion to harass the parties for settling their case (see 22 NYCRR 130-1.1[c][2])."

Labels:

Attorneys Fees,

contempt,

divorce,

FRIVOLOUS LAWSUITS

Tuesday, February 19, 2019

CLARIFICATION ON STATEMENT OF CLIENT'S RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES

As reported on February 15, effective that date, the "Statement of Client's Rights and Responsibilities" has been revised (22 NYCRR § 1400.2) for matrimonial actions only. 22 NYCRR § 1400 is for matrimonial actions only. "Section 1400.1. Application. This Part shall apply to all attorneys who, on or after November 30, 1993, undertake to represent a client in a claim, action or proceeding, or preliminary to the filing of a claim, action or proceeding, in either Supreme Court or Family Court, or in any court of appellate jurisdiction, for divorce, separation, annulment, custody, visitation, maintenance, child support, or alimony, or to enforce or modify a judgment or order in connection with any such claims, actions or proceedings. This Part shall not apply to attorneys representing clients without compensation paid by the client, except that where a client is other than a minor, the provisions of section 1400.2 of this Part shall apply to the extent they are not applicable to compensation."

As noted by an anonymous comment to the prior post "The general statement of client rights (22 NYCRR 1210.1) has not changed. It was last changed in 2018 to prohibit discrimination based on gender identity/expression." However, the current form on the New York State Bar Association site does not contain this correction (see https://www.nysba.org/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=27830); thus it would be suggested that anyone utilizing that form insert on paragraph 10 after "sexual orientation" and prior to "age" the words "gender identity, gender expression"

Monday, February 18, 2019

PRESIDENTS DAY OR UNIFORM MONDAY ACT DAY?

The Uniform Monday Holiday Act (Pub. L. 90–363, 82 Stat. 250, enacted June 28, 1968) is an Act of Congress that amended the federal holiday provisions of the United States Code to establish the observance of certain holidays on Mondays. The Act was signed into law on June 28, 1968, and took effect on January 1, 1971, and did not officially establish "Presidents Day", nor did it combine the observance of Lincoln's Birthday with Washington's Birthday. But the act placed federal observance of Washington's "birthday" in the week of February 15 to 21 and, since that week always falls between Lincoln's birthday (February 12) and Washington's (February 22), but never includes either date, popular references have given rise to the title, which recognizes both Presidents.

In New York, General Construction Law Section 24 designates both Lincoln's Birthday and Washington's Birthday as a separate state holiday:

"§ 24. Public holidays; half-holidays. The term public holiday includes the following days in each year: the first day of January, known as New Year's day; the third Monday of January, known as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. day; the twelfth day of February, known as Lincoln's birthday; the third Monday in February, known as Washington's birthday; the last Monday in May, known as Memorial day; the second Sunday in June, known as Flag day; the fourth day of July, known as Independence day; the first Monday in September, known as Labor day; the second Monday in October, known as Columbus day; the eleventh day of November, known as Veterans' day; the fourth Thursday in November, known as Thanksgiving day; and the twenty-fifth day of December, known as Christmas day, and if any of such days except Flag day is Sunday, the next day thereafter; each general election day, and each day appointed by the president of the United States or by the governor of this state as a day of general thanksgiving, general fasting and prayer, or other general religious observances. The term half-holiday includes the period from noon to midnight of each Saturday which is not a public holiday."

Labels:

holidays

Friday, February 15, 2019

STATEMENT OF CLIENT'S RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES HAS BEEN REVISED

Effective today, February 15, 2019, the "Statement of Client's Rights and Responsibilities" has been revised. An attorney shall provide a prospective client with a statement of client's rights and responsibilities at the initial conference and prior to the signing of a written retainer agreement. If the attorney is not being paid a fee from the client for the work to be performed on the particular case, the attorney may delete from the statement those provisions dealing with fees. The attorney shall obtain a signed acknowledgment of receipt from the client.

The statement shall be in the form found at this link: Revised Statement of Client's Rights and Responsibilities

Thursday, February 14, 2019

WHEN A PARTY DIES DURING A LITIGATION

This action started in 2014. A motion was made in 2017 after two of the defendants passed way.

U & Me Homes, LLC v County of Suffolk, 2019 NY Slip Op 01119, Decided on February 13, 2019. Appellate Division, Second Department:

"Generally, the death of a party divests a court of jurisdiction to act, and automatically stays proceedings in the action pending the substitution of a legal representative for the decedent pursuant to CPLR 1015(a)" (NYCTL 2004-A Trust v Archer, 131 AD3d 1213, 1214; see JP Morgan Chase Bank, N.A. v Rosemberg, 90 AD3d 713, 714; Neuman v Neumann, 85 AD3d 1138, 1139). "A motion for substitution pursuant to CPLR 1021 is the method by which the court acquires jurisdiction" over the deceased party's personal representative, and such a motion "is not a mere technicality" (Bossert v Ford Motor Co., 140 AD2d 480, 480; see Singer v Riskin, 32 AD3d 839, 840). "[A]ny determination rendered without such substitution will generally be deemed a nullity" (Singer v Riskin, 32 AD3d at 840; see NYCTL 2004-A Trust v Archer, 131 AD3d at 1214; JP Morgan Chase Bank, N.A. v Rosemberg, 90 AD3d at 714).

Here, the deceased defendants died before the plaintiff's motion was made and before the order appealed from was issued. Since a proper substitution had not been made, the Supreme Court should not have determined the merits of the plaintiff's motion, even to the extent that the plaintiff sought relief against other defendants and nonparties (see American Airlines Fed. Credit Union v Costello, 161 AD3d 819, 820; Aurora Bank FSB v Albright, 137 AD3d 1177, 1179; NYCTL 2004-A Trust v Archer, 131 AD3d at 1214). Under the circumstances, the court should have denied that branch of the plaintiff's motion which was for leave to enter a default judgment "on the ground that no substitution had been made" for the deceased defendants (American Airlines Fed. Credit Union v Costello, 161 AD3d at 821; see Aurora Bank FSB v Albright, 137 AD3d at 1179). Accordingly, we affirm the order insofar as appealed from (see generally American Airlines Fed. Credit Union v Costello, 161 AD3d at 821; Aurora Bank FSB v Albright, 137 AD3d at 1179)."

Labels:

Death,

LITIGATION,

Stay

Wednesday, February 13, 2019

WHEN IS AN INTERN AN EMPLOYEE?

Velarde v. GW GJ, INC., Court of Appeals, 2nd Circuit, February 5, 2019:

"In Glatt v. Fox Searchlight Pictures, Inc., 811 F.3d 528 (2d Cir. 2015),

we addressed the application of certain federal and state employment

laws to activities performed in a commercial setting by temporary

"interns." We applied a "primary beneficiary" test: if, under certain

enumerated circumstances, the intern is the "primary beneficiary" of the

relationship, then the host entity is not the intern's employer and has

no legal obligation to pay compensation under those laws; if, on the

other hand, the host entity is the "primary beneficiary" of the

relationship, then the entity is an employer and federal and state

employment laws—in particular, the Fair Labor Standards Employment Act,

29 U.S.C. §§ 201 et seq. ("FLSA"), and Articles 6 and 19 of the New York Labor Law §§ 190, 650 et seq. ("NYLL")—impose compensation obligations.

In the case at bar, we consider the applicability of this test to individuals enrolled in a for-profit vocational academy who are preparing to take a state licensure examination and who must first fulfill state minimum training requirements. These individuals fulfill those requirements by working under Academy supervision for a defined number of hours, without pay. We determine that the Glatt test governs in the for-profit vocational training context, and we further conclude that here, the plaintiff, former student of the Academy was the primary beneficiary of the relationship, thus excusing the latter from potential compensation obligations under FLSA or NYLL related to plaintiff's limited work there as a trainee."

In the case at bar, we consider the applicability of this test to individuals enrolled in a for-profit vocational academy who are preparing to take a state licensure examination and who must first fulfill state minimum training requirements. These individuals fulfill those requirements by working under Academy supervision for a defined number of hours, without pay. We determine that the Glatt test governs in the for-profit vocational training context, and we further conclude that here, the plaintiff, former student of the Academy was the primary beneficiary of the relationship, thus excusing the latter from potential compensation obligations under FLSA or NYLL related to plaintiff's limited work there as a trainee."

Tuesday, February 12, 2019

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE VICTIMS AND LEASE LIABILITY

RIVERWALK ON THE HUDSON, INC. v. Culliton, 2018 NY Slip Op 28350 - NY: City Court 2018:

"Beginning with statutory defenses, RPL 227-c provides a method for victims of domestic violence to terminate a lease. RPL 227-c (1), in pertinent part, provides: "[A] tenant for whose benefit any order of protection has been issued shall be permitted to terminate [her] lease and surrender possession of the leasehold premise and be released from any liability to pay to the lessor rent for the time subsequent to the date of termination of such lease in accordance with subdivision two." RPL 227-c (2) sets forth the required procedural steps to terminate the lease.

Morgan qualifies for the protections afforded by RPL 227-c. However, Morgan, who appeared without a lawyer in either Family Court or this court, never invoked or sought the aid of RPL 227-c at any time. Morgan, the court surmises, was unfamiliar with the statute and sadly, nothing in the law requires a court to explain this important statutory right to victims of domestic abuse. Nevertheless, this court lacks the power to retroactively apply the protections of RPL 227-c for Morgan's benefit; therefore, the statute does not bar Riverwalk's recovery of rent arrears against Morgan.

Morgan may have a common law contract defense that excuses her from liability. The question becomes whether RPL 227-c is the exclusive method for a domestic violence victim to be absolved from rent owed under a lease agreement. To this question, there is no obvious answer. On the one hand, the statute creates a right for a domestic violence victim to break a lease and there would be a thick irony to interpret such a statute to restrict or to eliminate other rights. On the other hand, the statute crafts a balance between victims' and landlords' economic rights and the balance having been set by the Legislature should not be disturbed by a court.

Ultimately, whether RPL 227-c eliminates common law contracts defenses to liability under a lease hinges on whether RPL 227-c "abrogates, or merely derogates, the common law. Abrogation means the entire repeal and annulment of a law; derogation relates to the partial repeal or abolishing of a law, as by a subsequent act which limits its scope or impairs its utility and force" (Fumarelli v. Marsam Dev. Inc., 92 NY2d 298, 306 [1998] [internal quotations and citations omitted, italics in the original]).

The strongest basis to find abrogation is the omission of a subdivision of RPL 227-c indicating that the common law remains intact. Indeed, the Legislature has, in other sections of the RPL, made its intentions not to abrogate other rights explicit. For example, RPL 227-d which protects domestic violence victims from discrimination contains a clause which provides: "Nothing in this section shall be construed as limiting, diminishing, or otherwise affecting any rights under existing law" (RPL 227-d [6]). RPL 227-c has no language or clause that mirrors RPL 227-d (6).

However, finding that a statute abrogates common law rights by the omission of an explicit clause preserving them is not the preferred method of statutory construction. Rather, the "general rule of statutory construction [is] that a clear and specific legislative intent is required to override the common law" (Hechter v. New York Life Ins. Co., 46 NY2d 34, 39 [1978]). Thus, "when the common law gives a remedy, and another remedy is provided by statute, the latter is cumulative, unless made exclusive by the statute" (Katz 737 Corp. v. Cohen, 104 AD3d 144, 159 [1st Dept 2012] [internal quotation marks and citation omitted]; see e.g. Fleury v. Edwards, 14 NY2d 334, 338 [1964] [holding that common law as to admissibility of evidence given by witness who has died was still applicable notwithstanding enactment of rule respecting admissibility of such testimony]). The court holds, therefore, that RPL 227-c neither displaces nor eliminates any common law contract defense that may be available to Morgan.

The common law doctrine of unconscionability seems applicable here. A term of a contract is unconscionable when it is shockingly unjust or unfair or because, procedurally, an unfair term was obtained through unconscionable means, or because of a combination of both factors (People by Abrams v. Two Wheel Corp., 71 NY2d 693, 699 [1988]). The doctrine is designed to prevent oppression (Rzepko v. GIA Gem Trade Lab., Inc., 115 Misc 2d 755, 758 [Sup Ct, New York County, 1982]). An issue of unconscionability is a matter to be decided by a court (Wilson Trading Corp. v. David Ferguson, Ltd., 23 NY2d 398, 403-04 [1968]).

Normally, whether the contract is unconscionable in whole or in part is viewed from the time of its formation (see e.g. RPL 235-c [allowing a court to void or limit "any clause of the lease to have been unconscionable at the time it was made] [emphasis added]). In this case, nothing in the lease agreement is unconscionable on its face. The joint and several liability clause comports with traditional contract principles. It is simply a clause that allocates the risks between the parties and not in an unfair manner. After all, allocation of risk is an essential purpose of a contract (Comprehensive Bldg. Contractors Inc. v. Pollard Excavating Inc., 251 AD2d 951, 952 [3d Dept 1998]). The Cullitons assumed the risk of non-payment jointly—even if "unforeseen circumstances [were to] make performance burdensome" (Kel Kim Corp. v. Central Mkts., 70 NY2d 900, 902 [1987]).

This case is unusual in that the unconscionability inquiry revolves around events that occurred after the execution of the contract. Thus, at least initially, the question is whether a legitimate clause can be rendered impotent because its implementation in a peculiar circumstance produces an unconscionable result. That is, can a court declare a facially valid contract clause invalid as applied to a particular situation. There appears to be no New York authority directly answering this question.[4] However, courts regularly distinguish between the facial validity and the as applied validity of a law (see e.g. People v. Stuart, 100 NY2d 412, 421 [2003] [discussing the difference between facial validity and as applied validity]). The court will adopt what is routine statutory analysis to the contract issue here (cf. Slamon v. Carrizo LLC, No. 3:16-CV-2187 (Mariani, J.), 2017 WL 3877856, at *4 (M.D. Pa. Sept. 5, 2017) (noting that it is not unusual for courts to sometimes apply rules of statutory construction to aid their interpretations of a contract])

.

The court will, therefore, determine if the joint and several liability clause is unconscionable when applied to the facts in this case. What gave rise to Morgan leaving her apartment was a judicial order which prohibited the Cullitons from living together. The order was necessary to protect Morgan from harm. Morgan, the victim, deemed that living with her mother was safer than the vulnerability of living alone in the apartment. Her choice allowed Robert to keep possession of the apartment— a fact that Riverwalk was aware of by early June. When June's rent went unpaid, Riverwalk did not seek an eviction; when July's rent went unpaid, it did not seek an eviction. Rather, Riverwalk waited all the way until August's rent was due before it made a case returnable in this court.

Riverwalk asks the court to hold Morgan responsible for $3,498 of rent arrears pursuant to the joint and several liability clause of the lease. The court will not do so. A woman who is a victim of domestic violence should not be forced to pay the rent of her abuser. To sustain the contrary proposition, as Riverwalk seeks, would be shockingly unjust and unfair which is the very definition of an unconscionable act (Black's Law Dictionary [10th ed. 2014]). Therefore, the court holds the joint and several liability clause, as applied to the facts in this case, is unconscionable and thus void as to Morgan Culliton.

No monetary judgment will be entered against Respondent Morgan Culliton. The monetary judgment against Robert Culliton is undisturbed. Riverwalk's remedy for rent arrears lies against Robert Culliton alone."

Monday, February 11, 2019

FREE MORTGAGE FORECLOSURE CLINIC TODAY

For more information, contact Nassau County Bar Association, 15th and West Streets, Mineola, NY 11501 at (516) 747-4070

Friday, February 8, 2019

BUSINESS OWNER LIABILITY FOR THIRD PARTY ASSAULTS TO PATRONS

For a business, sometimes what happens outside the premises can be a liability. This was discussed in an earlier blog post with respect to landlords. See https://jmpattorney.blogspot.com/2018/08/is-landlord-liable-for-3rd-party.html

This photo of Table Talk Diner is courtesy of TripAdvisor - this case does not involve Table Talk Diner.

Oblatore v 67 W. Main St., LLC, 2019 NY Slip Op 00892, Decided on February 6, 2019, Appellate Division, Second Department:

"On the early morning hours of August 25, 2007, the plaintiff and his friends allegedly were attacked from behind by a group of individuals in a parking lot located adjacent to an establishment owned and/or operated by the defendants 67 West Main Street, LLC, Havens Brewery, LLC, Brick House Brewery & Restaurant, Brick House Brewing Co., and Havens Brewery, LLC, doing business as Brick House Brewery & Restaurant, also known as Brick House Brewing Co. (hereinafter collectively the defendants). The plaintiff subsequently commenced this action alleging, inter alia, that the defendants were negligent in failing to control the conduct of persons on their property. The defendants moved for summary judgment dismissing the complaint insofar as asserted against them. The Supreme Court granted the motion, and the plaintiff appeals.

"Landowners, as a general rule, have a duty to exercise reasonable care to prevent harm to patrons on their property" (Kranenberg v TKRS Pub, Inc., 99 AD3d 767, 768; see D'Amico v Christie, 71 NY2d 76, 85; Hegarty v Tracy, 125 AD3d 804, 805). "However, an owner's duty to control the conduct of persons on its premises arises only when it has the opportunity to control such conduct, and is reasonably aware of the need for such control" (Kranenberg v TKRS Pub, Inc., 99 AD3d at 768 [internal quotation marks omitted]; see Afanador v Coney Bath, LLC, 91 AD3d 683, 683-684; Giambruno v Crazy Donkey Bar & Grill, 65 AD3d 1190, 1192). "Thus, the owner of a public establishment has no duty to protect patrons against unforeseeable and unexpected assaults" (Giambruno v Crazy Donkey Bar & Grill, 65 AD3d at 1192; see Kranenberg v TKRS Pub, Inc., 99 AD3d at 768; Afanador v Coney Bath, LLC, 91 AD3d at 683-684).

Here, the defendants established their prima facie entitlement to judgment as a matter of law by submitting evidence demonstrating that the attack on the plaintiff was unforeseeable and unexpected (see Hegarty v Tracy, 125 AD3d at 805; Kranenberg v TKRS Pub, Inc., 99 AD3d at 768; Giambruno v Crazy Donkey Bar & Grill, 65 AD3d at 1192). In opposition, the plaintiff failed to raise a triable issue of fact (see Zuckerman v City of New York, 49 NY2d 557). Accordingly, we agree with the Supreme Court's determination granting the defendants' motion for summary judgment dismissing the complaint insofar as asserted against them."

Labels:

Assault,

Business,

Liability,

Negligence,

Personal Injury

Thursday, February 7, 2019

CHILD CUSTODY - DETERMINATION OF PARENTHOOD IN NON-TRADITIONAL FAMILIES

This is from the NYLJ Case Digest Summary - The Appellate Division remanded this case to consider equitably estopping the biological mother from denying her former partner's parentage of her son. The former partner wanted access time with AH pendente lite and relied on court's prior finding interim access was warranted to maintain consistency with AH's experience with her. Here, the court addressed the interim access petition in view of AH's best interest "despite absence of specific statutory authority or applicable case law, directing parties to appear for a framed issue hearing" noting that "ultimate determination of parenthood would be predicated on AH's best interests, setting out criteria for consideration...."

K.G. v. C.H., NYLJ 2/4/19, Date filed: 2019-01-18, Court: Supreme Court, New York, Judge: Justice Frank Nervo, Case Number: 309154/2016:

"The parties urged this Court to establish criteria for equitable estoppel in order that any appointed forensic expert, as well as all others concerned with the orderly progression of this matter, be properly guided. The elements of equitable estoppel are established by this Court as set forth below. Prior to the date of this order, the parties had been provided the opportunity to object to any or all elements of these criteria on any ground appropriate, particularly in view of objections previously asserted that disputes of this nature present an inherent heightened legal barrier to nontraditional family members. Those objections were found to be entirely without merit by the Appellate Division (163 A.D.3d 67, 78-79). This Court maintains the concern that no criteria here established present any heightened legal barrier, or any unique challenge or unique difficulty whatsoever for members of LGBTQ or other nontraditional families. To date, neither party has presented any objection, and the Court remains available to address any objection which may come to light as this matter proceeds. A number of similar petitions are currently in various stages of litigation within and without the State of New York, and a number of courts are contemporaneously establishing criteria for equitable estoppel as a result of the different records made on different days (as presciently predicted by the Court in Brooke S.B. v. Elizabeth A.D.D., 28 NY3d 1, 28). Therefore, for purposes of distinct reference and clarity, the following criteria shall be designated:

JUDGE NERVO’s CRITERIA FOR EQUITABLE ESTOPPEL

The ultimate determination of parenthood shall be predicated upon the best interests of the child. In consideration thereof, the court will determine and consider the extent to which the petitioner, by clear and convincing evidence:

(1) undertook full and permanent fiscal responsibilities for the child without expectation of financial compensation;

(2) resided with the child;

(3) affirmatively held out the child as her own, or what objective observation of the relationship by others in their community would demonstrate;

(4) otherwise engaged in consistent caretaking of the child;

(5) had been in a parental role for a length of time sufficient to have established with the child a bonded, dependent, parental relationship;

(6) is recognized or acknowledged as parental by the child;

(7) has a close and deep emotional bond with the child;

(8) bonded a dependent relationship with the child, supported, or facilitated, affirmatively or impliedly, by the legal parent;

(9) engaged in decision-making with the legal parent with respect to major issues concerning the child including, but not limited to, health, welfare, education, and any participation in organized religion;

(10) is or was part of any formalized relationship with the legal parent and/or the child; and

(11) how the abrupt, or continued, termination from any and all contact with the petitioner has, or would continue to, adversely affect the child, if at all."

Wednesday, February 6, 2019

DIVORCE - FAMILY TRUST

In this case, the parties established a family trust with funds allegedly held from Wife's separate accounts and now Wife wants a distribution. With high income or asset families, or with grey divorces, family trusts may be an item to be seriously considered.

Oppenheim v Oppenheim, 2019 NY Slip Op 00610, Decided on January 30, 2019, Appellate Division, Second Department:

"The defendant's main contention on this appeal is that the Supreme Court should have awarded her equitable distribution of the value of the principal in the family trust as of the date of trial, based on the plaintiff's alleged inequitable conduct in the formation of the family trust. The defendant contends that the plaintiff "commandeered" the family trust, the funding of which came from assets held in her name. The defendant points out that, although the family trust was ostensibly intended to benefit the parties' children and their descendants, the plaintiff had the power to discharge the independent trustee and was himself a permissible beneficiary. The plaintiff also retained a testamentary power of appointment exercisable in favor of any beneficiary, not just the children. Notably, the defendant has never challenged the validity of the family trust and has not sought to set it aside. Moreover, she seeks equitable distribution not of the actual funds held by the family trust, but only distribution of the amount of the assets in the trust from other assets held by the plaintiff. The defendant has not alleged that the plaintiff actually sought distribution to himself of any of the family trust principal.

Trial courts are vested with broad discretion in determining equitable distribution of marital property. Unless the court has improvidently exercised that discretion, its determination should not be disturbed on appeal (see Linenschmidt v Linenschmidt, 163 AD3d 949, 950; Gafycz v Gafycz, 148 AD3d 679, 680; Alper v Alper, 77 AD3d 694, 695). Moreover, when the Supreme Court has determined the issue of equitable distribution after a nonjury trial, the credibility assessments underlying its determination are entitled to great weight on appeal (see Linenschmidt v Linenschmidt, 163 AD3d at 950; Alper v Alper, 77 AD3d at 695). Here, contrary to the defendant's contention, the court providently exercised its discretion in declining to award equitable distribution of the value of the family trust. Giving due deference to the court's credibility assessments, we agree that the evidence as to the circumstances surrounding, among other things, the creation of the family trust and the terms of the trust itself, do not support the defendant's contentions that the plaintiff acted inequitably in regard to the formation of the family trust (see Weidman v Weidman, 162 AD3d 720, 723-724)."

Labels:

divorce,

Equitable Distribution,

Trusts

Tuesday, February 5, 2019

MORTGAGE FORECLOSURE - STANDING DEFENSE WAIVED BUT REVIVED

This mistake was costly as the bank appears to have "waived the waiver." A drafting suggestion may have been: "The standing defense was waived as defendant did not raise it in a pre-answer motion to dismiss or as an affirmative defense. But if (assuming arguendo) this court does not find the defense waived....

BAC Home Loans Servicing, LP v Alvarado, 2019 NY Slip Op 00584. Decided on January 30, 2019, Appellate Division, Second Department:

"The defense of lack of standing in an action to foreclose a mortgage is waived if the defendant does not raise it in a pre-answer motion to dismiss or as an affirmative defense (see CPLR 3018[b]; US Bank Nat. Assn. v Nelson, ___ AD3d ___, 2019 NY Slip Op 00494 [2d Dept 2019]; Bank of N.Y. Trust Co., N.A. v Chiejina, 142 AD3d 570, 572; One W. Bank, FSB v Vanderhorst, 131 AD3d 1028, 1028; see also Matter of Fossella v Dinkins, 66 NY2d 162, 167). Here, in opposition to the plaintiff's motion for summary judgment and in support of their cross motion to dismiss, the defendants argued that the plaintiff lacked standing to commence this action. The plaintiff, in its "reply . . . in further support of plaintiff's motion for summary judgment, and in opposition to defendant's [sic] cross-motion to dismiss," entirely disregarded the defendants' waiver of the standing defense. Instead, the plaintiff sought to establish that it had standing to commence the action. Now, having litigated the standing defense on the merits in the Supreme Court—both on the original motion and in opposition to reargument—the plaintiff argues on appeal that the issue of standing was waived. Having neglected to raise that dispositive issue in the Supreme Court, the plaintiff may not raise it for the first time on this appeal (see Hurley v Tolfree, 308 NY 358, 363; Robles v Brooklyn Queens Nursing Home, Inc., 131 AD3d 1032, 1033; see generally Arthur Karger, Powers of the New York Court of Appeals § 17.1 at 591-592, et seq. [3d ed rev 2005]), and we decline to address it (cf. Sega v State of New York, 60 NY2d 183, 190 n 2; HSBC Bank USA, N.A. v Ozcan, 154 AD3d 822, 824).

The plaintiff also failed, on the merits, to establish prima facie that it had standing to commence the action. The loan servicer's affidavit, which asserted that the named plaintiff "was in possession of the Note at the time of commencement of this action," provided no specifics as to the date of delivery or the date of commencement. The plaintiff's conclusory assertion as to possession on the date of commencement is insufficient to establish standing (see Central Mtge. Co. v Jahnsen, 150 AD3d 661, 663; Deutsche Bank Natl. Trust Co. v Idarecis, 133 AD3d 702, 703-704; cf. Aurora Loan Servs., LLC v Taylor, 25 NY3d 355, 361; U.S. Bank, N.A. v Noble, 144 AD3d 786, 788; Nationstar Mtge., LLC v Weisblum, 143 AD3d 866, 867). Moreover, the plaintiff's alternative ground for establishing standing is without merit (see U.S. Bank, N.A. v Noble, 144 AD3d at 788; Bank of N.Y. v Silverberg, 86 AD3d 274, 282). Accordingly, the Supreme Court should have denied the plaintiff's motion, inter alia, for summary judgment on the complaint and an order of reference."

Labels:

Mortgage Foreclosure,

Standing,

Waiver

Monday, February 4, 2019

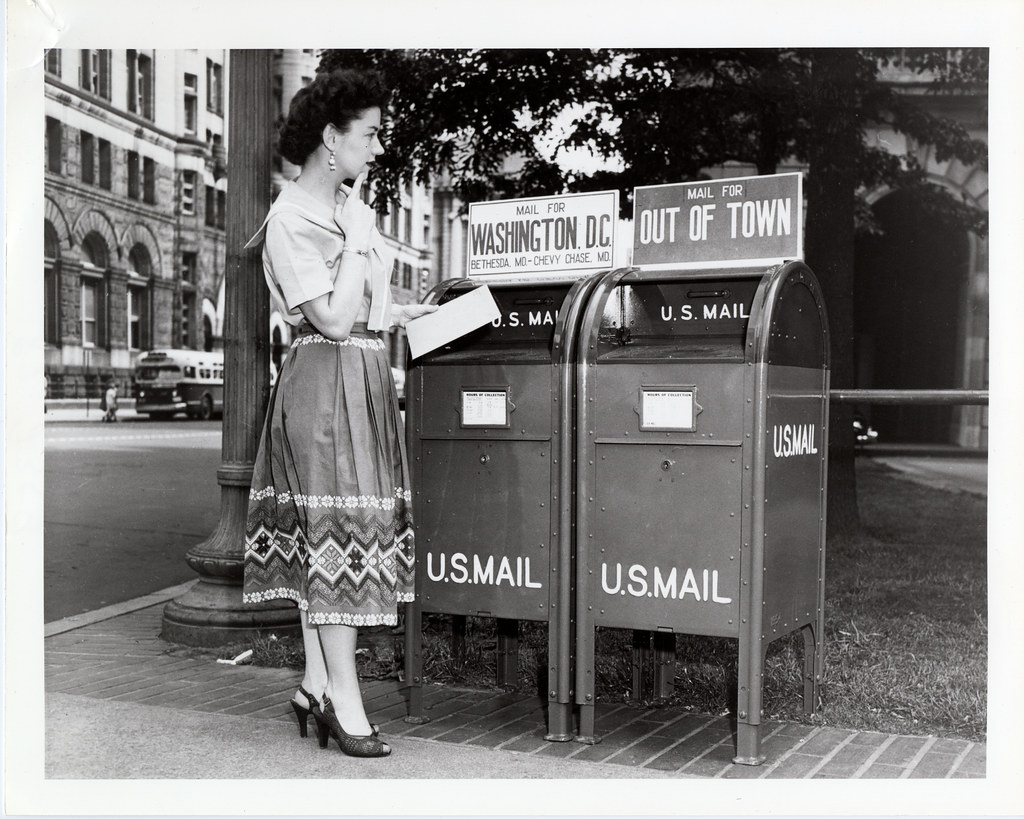

MORTGAGE FORECLOSURE - RPAPL 1304 PROOF OF MAILING

The rules of evidence apply to motions for summary judgment,

Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. v Moran, 2019 NY Slip Op 00637, Decided on January 30, 2019, Appellate Division, Second Department:

"Proper service of RPAPL 1304 notice on the borrower or borrowers is a condition precedent to the commencement of a foreclosure action, and the plaintiff has the burden of establishing satisfaction of this condition (see JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. v Kutch, 142 AD3d 536, 537; Flagstar Bank, FSB v Jambelli, 140 AD3d 829, 830). The statute requires that such notice be [*2]sent by registered or certified mail, and also by first-class mail, to the last known address of the borrower (see RPAPL 1304[2]). By requiring the lender or mortgage loan servicer to send the RPAPL 1304 notice by registered or certified mail and also by first-class mail, the Legislature implicitly provided the means for the plaintiff to demonstrate its compliance with the statute, i.e., by submission of proof of mailing by the post office (see CitiMortgage, Inc. v Pappas, 147 AD3d 900, 901).

Here, in support of its motion, the plaintiff failed to demonstrate, prima facie, its compliance with the requirements of RPAPL 1304. In this regard, the plaintiff failed to submit an affidavit of service or proof of mailing by the post office evincing that it properly served the defendant pursuant to RPAPL 1304. Contrary to the plaintiff's contention, its submission of an affidavit of the employee of its servicer was not sufficient to establish that the notices were sent to the defendant in the manner required by RPAPL 1304. While mailing may be proved by documents meeting the requirements of the business records exception to the hearsay rule under CPLR 4518 (see HSBC Bank USA, N.A. v Ozcan, 154 AD3d 822, 827), here, the affiant did not aver that he was familiar with the servicer's mailing practices and procedures and therefore did not establish proof of a standard office practice and procedure designed to ensure that items are properly addressed and mailed (see U.S. Bank N.A. v Henry, 157 AD3d 839, 841-842; Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. v Lewczuk, 153 AD3d 890, 892; M & T Bank v Joseph, 152 AD3d 579, 580; Citibank, N.A. v Wood, 150 AD3d 813, 814). The affiant's unsubstantiated and conclusory statements were insufficient to establish that the RPAPL 1304 notice was mailed to the defendant by first-class and certified mail (see U.S. Bank N.A. v Henry, 157 AD3d at 841-842; Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. v Lewczuk, 153 AD3d at 892; M & T Bank v Joseph, 152 AD3d at 580; Citibank, N.A. v Wood, 150 AD3d at 814). Accordingly, the Supreme Court should have denied those branches of the plaintiff's motion which were for summary judgment on the complaint insofar as asserted against the defendant and for an order of reference, regardless of the sufficiency of the opposing papers (see Winegrad v New York Univ. Med. Ctr., 64 NY2d 851, 853)."

Labels:

Mortgage Foreclosure,

Proof of Mailing,

RPAPL 1304

Friday, February 1, 2019

MORTGAGE FORECLOSURE - A SUCCESSFUL STANDING DEFENSE IN FIRST ACTION DEFEATS SECOND ACTION

This is an example of where a homeowner won a battle but lost the war. It illustrates a problem of asserting the standing defense.

US Bank Trust, N.A. v Williams, 2019 NY Slip Op 00634, Decided on January 30, 2019, Appellate Division, Second Department:

"In March 2015, the plaintiff commenced this action to foreclose a mortgage alleging, inter alia, that the defendant Una Williams (hereinafter the defendant) had defaulted in her mortgage payment due July 1, 2006, and on all payments due thereafter. Thereafter, the defendant moved pursuant to CPLR 3211(a)(3) and (5) to dismiss the complaint for lack of standing and as barred by the statute of limitations. The Supreme Court denied the motion, and the defendant appeals.

…….

As to that branch of the defendant's motion which was pursuant to CPLR 3211(a)(5) to dismiss the complaint as barred by the applicable six-year statute of limitations (see CPLR 213[4]), "[w]ith respect to a mortgage payable in installments, separate causes of action accrue[ ] [*2]for each installment that is not paid, and the statute of limitations begins to run, on the date each installment becomes due" (Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. v Burke, 94 AD3d 980, 982; see U.S. Bank N.A. v Gordon, 158 AD3d 832, 835; Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. v Cohen, 80 AD3d 753, 754). However, "even if a mortgage is payable in installments, once a mortgage debt is accelerated, the entire amount is due and the Statute of Limitations begins to run on the entire debt" (EMC Mtge. Corp. v Patella, 279 AD2d 604, 605; see U.S. Bank N.A. v Gordon, 158 AD3d at 835; Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. v Burke, 94 AD3d at 982). "Where the acceleration of the maturity of a mortgage debt on default is made optional with the holder of the note and mortgage, some affirmative action must be taken evidencing the holder's election to take advantage of the accelerating provision, and until such action has been taken the provision has no operation" (Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. v Burke, 94 AD3d at 982-983; see U.S. Bank N.A. v Gordon, 158 AD3d at 835; Esther M. Mertz Trust v Fox Meadow Partners, 288 AD2d 338, 340). "[U]nder certain circumstances, the commencement of a foreclosure action may be sufficient to put the borrower on notice that the option to accelerate the debt has been exercised" (U.S. Bank N.A. v Gordon, 158 AD3d at 836; see Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. v Burke, 94 AD3d at 983; EMC Mtge. Corp. v Smith, 18 AD3d 602, 603).

Here, the defendant contended that the commencement of a prior mortgage foreclosure action by HSBC Mortgage Services Inc. (hereinafter HSBC), in November 2006 was sufficient to accelerate the mortgage debt. However, in support of her motion, the defendant submitted a copy of an amended order of the Supreme Court dated September 30, 2014, which granted the defendant's motion to dismiss the prior mortgage foreclosure action on the ground that HSBC did not have standing to commence that action because it was not the holder of the note and mortgage at the time that action was commenced. Since HSBC was not the holder of the note and mortgage at the time of the commencement of the prior mortgage foreclosure action, it lacked the authority to accelerate the debt through the complaint in that action (see Milone v US Bank National Association, 164 AD3d 145; U.S. Bank N.A. v Gordon, 158 AD3d at 836; Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. v Burke, 94 AD3d at 983; EMC Mtge. Corp. v Smith, 18 AD3d at 603). Thus, the defendant failed to meet her initial burden of demonstrating, prima facie, that this action was untimely (see U.S. Bank N.A. v Gordon, 158 AD3d at 835-836; Campone v Panos, 142 AD3d 1126, 1127).

Accordingly, we agree with the Supreme Court's determination to deny that branch of the defendant's motion which was pursuant to CPLR 3211(a)(5) to dismiss the complaint as barred by the statute of limitations."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)