Tuesday, February 28, 2017

DIVORCE - ARE ASSETS IN TRUST SUBJECT TO EQUITABLE DISTRIBUTION

Markowitz v. Markowitz, 2017 NY Slip Op 296 - NY: Appellate Div., 2nd Dept. 2017:

"The defendant correctly contends that the Supreme Court erred in awarding the plaintiff the cash surrender value of the subject Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance policy (hereinafter the policy). The policy is held by the 1995 Jeffrey S. Markowitz Irrevocable Trust. While marital assets placed in a trust may be subject to equitable distribution (see Domestic Relations Law § 236[B][5]; Riechers v Riechers, 267 AD2d 445), the trust here is irrevocable, and neither party is a trustee with the power to transfer control of the trust assets. Accordingly, the trust assets are unavailable to either party. The defendant's contention that the trust has been implicitly revoked is without merit (see EPTL 7-1.9[a]). Accordingly, the policy should not have been included in the distributive award (cf. Wortman v Wortman, 11 AD3d 604, 607)."

Labels:

divorce,

Equitable Distribution,

marital property,

Trusts

Monday, February 27, 2017

MORTGAGE FORECLOSURE CLINIC TODAY

I will be volunteering today, Monday February 27, at the Nassau County Bar Association's free clinic for Mortgage Foreclosure, Bankruptcy and Superstorm Sandy issues, from 3pm to 6pm.

For more information, contact Nassau County Bar Association, 15th and West Streets, Mineola, NY 11501 at (516) 747-4070

Friday, February 24, 2017

CHILD CUSTODY - THE DANGERS OF RELOCATING WITHOUT COURT ORDER

MATTER OF GOODMAN v. Jones, 2017 NY Slip Op 305 - NY: Appellate Div., 2nd Dept. 2017:

"

The father and the mother, who never married, have one child in common, born in 2012. The parties had been living together but separated in March 2014, and the father left the family home. Approximately one week later, he filed a petition for custody of the child. At about the same time, the mother left New York and moved to Mississippi with the child without informing the father. Following a court order, the child was returned to New York and the father was granted temporary custody pending determination of his petition. The mother then filed a petition for custody of the child, and subsequently amended the petition to include a request to relocate with the child to Mississippi. After a hearing, the Family Court awarded the father sole custody of the child with visitation to the mother and, in effect, denied the mother's amended petition. The mother appeals.

In making an initial custody or visitation determination, the Family Court must consider what arrangement is in the best interests of the child under the totality of the circumstances (see Eschbach v Eschbach, 56 NY2d 167, 171; Matter of Saravia v Godzieba, 120 AD3d 821; cf. Domestic Relations Law § 70[a]; Family Ct Act § 651[b]). In determining the child's best interests, the court should consider a number of factors, including the relative fitness of the parents, the quality of the respective home environments, the quality of parental guidance, the ability of each parent to provide for the child's emotional and intellectual development, and the effect an award of custody to one parent might have on the child's relationship with the other parent (see Eschbach v Eschbach, 56 NY2d at 172-173; Matter of Elliott v Felder, 69 AD3d 623; Miller v Pipia, 297 AD2d 362, 364). Willful interference with the other parent's right to visitation, such as when a parent absconds with the child, is "an act so inconsistent with the best interests of the [child] as to, per se, raise a strong probability that the [offending party] is unfit to act as custodial parent" (Entwistle v Entwistle, 61 AD2d 380, 384-385; see Matter of Pettiford v Clarke, 133 AD3d 666, 667; Matter of Joosten v Joosten, 282 AD2d 748, 748; Matter of Glenn v Glenn, 262 AD2d 885, 887). In addition, in the context of an initial custody determination, a proposed relocation is one factor for the court to consider in determining what is in the child's best interests (see Matter of Gadsden v Gadsden, 144 AD3d 1035; Matter of Adegbenle v Perez, 135 AD3d 857, 859; Matter of Wright v Stewart, 131 AD3d 1256, 1257).

Since a custody determination depends to a great extent upon an assessment of the character and credibility of the parties and witnesses, deference is accorded to the hearing court's findings, and such findings will not be disturbed unless they lack a sound and substantial basis in the record (see Matter of Gooler v Gooler, 107 AD3d 712, 712; Matter of Conforti v Conforti, 46 AD3d 877). Here, the Family Court's determination that the child's best interests would be served by awarding the father sole custody has a sound and substantial basis in the record and should not be disturbed."

Labels:

child custody,

relocation

Thursday, February 23, 2017

UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE - DISSENTING VIEW FROM THE COURT OF APPEALS

I disagree with the majority's conclusion that the determination of the Unemployment Insurance Appeal Board (the Board) is not supported by substantial evidence. Whether an employer-employee relationship exists "necessarily is a question of fact" (Matter of Villa Maria Inst. of Music [Ross], 54 NY2d 691, 692 [1981]; see Matter of Di Martino [Buffalo Courier Express Co. — Ross], 59 NY2d 638, 641 [1983]). The Board must determine whether the employer exercised control over the results produced or the means used to achieve the results, with control over the means being more important (see Matter of Empire State Towing & Recovery Assn., Inc. [Commissioner of Labor], 15 NY3d 433, 437 [2010]). Nevertheless, "no one factor is determinative" (Matter of Concourse Ophthalmology Assoc. [Roberts], 60 NY2d 734, 736 [1983]). We have stated that "the determination of the appeal board, if supported by substantial evidence on the record as a whole, is beyond further judicial review even though there is evidence in the record that would have supported a contrary conclusion" (id. [emphasis added]; see Matter of MNORX, Inc. [Ross], 46 NY2d 985, 986 [1979]).

The majority relies on the evidence in the record supporting a determination that Yoga Vida's non-staff yoga instructors were independent contractors in concluding that the substantial evidence standard was not met (see majority op at 3). Yet the majority ignores the evidence in the record that does support the Board's determination that the non-staff instructors were employees. For example, there is evidence in the record that Yoga Vida generally recruits its clients, determines what fee to charge for its classes, and collects that fee directly from the students attending the classes. Once Yoga Vida determines the class schedule and posts that schedule on its website, the non-staff yoga instructors are not free to unilaterally alter the time or length of the class, the type of class taught, or the difficulty level, and it is Yoga Vida that sets which classes will be taught and when. The non-staff instructors are responsible for finding a suitable substitute instructor if they are unable to teach their scheduled class, and if the non-staff instructor cannot find a suitable replacement, Yoga Vida will provide its own substitute. Non-staff instructors are required to notify Yoga Vida of any substitution so that it can update its schedule, and Yoga Vida considers whether a non-staff instructor frequently has a substitute teach his or her class in determining whether to continue its relationship with that instructor. Furthermore, although non-staff instructors are free to tell their students about other locations at which they teach, Yoga Vida considers whether a non-staff instructor has advertised for a class directly conflicting with a Yoga Vida class in determining whether to continue its relationship with that instructor.

In summary, the majority has examined the evidence before the Board and concluded that the evidence weighs more heavily in favor of a conclusion that the non-staff instructors are independent contractors. It is the role of the Board, however, and not this Court, to weigh the factual evidence and arrive at a conclusion (see Villa Maria Inst. of Music, 54 NY2d at 693; MNORX, Inc., 46 NY2d at 986). If the evidence "reasonably supports the [B]oard's choice, we may not interpose our judgment to reach a contrary conclusion" (MNORX, Inc., 46 NY2d at 986). We have described substantial evidence as "[m]ore than seeming or imaginary" but "less than a preponderance of the evidence" (300 Gramatan Ave. Assoc. v State Div. of Human Rights, 45 NY2d 176, 180 [1978]). We have further stated that a "practical test" for determining whether substantial evidence exists is to "measur[e] the evidence against the standard of sufficiency such as to require a court to submit it as a question of fact to a jury" (id. at 181).

Here, the evidence reasonably supports the Board's conclusion that the non-staff instructors are Yoga Vida's employees, "even though there is evidence in the record that would have supported a contrary conclusion" (Concourse Ophthalmology Assoc., 60 NY2d at 736). In interposing its own judgment for that of the Board, the majority has disregarded the substantial evidence standard of review and erroneously denied the non-staff instructors employment benefits to which the Board determined they were entitled. I respectfully dissent."

Wednesday, February 22, 2017

UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE - FROM THE COURT OF APPEALS

MATTER OF YOGA VIDA NYC, INC. v. Commissioner of Labor, 2016 NY Slip Op 6940 - NY: Court of Appeals 2016:

"The order of the Appellate Division should be reversed, with costs, and the matter remitted to that court with directions to remand to respondent for further proceedings in accordance with this memorandum. Yoga Vida NYC, Inc. operates a yoga studio in Manhattan. It offers classes taught by both staff instructors and non-staff instructors, and classifies the latter as independent contractors. In May 2010, the Commissioner of Labor issued a determination that Yoga Vida was liable for additional unemployment contributions, effective October 1, 2009, based on its finding that the non-staff instructors are employees. Yoga Vida disputed that determination. A hearing was held before an Administrative Law Judge (ALJ), who sustained Yoga Vida's objection, concluded that the non-staff instructors are independent contractors and overruled the determination. The Commissioner appealed the ALJ's decision to the Unemployment Insurance Appeal Board. The Board overruled Yoga Vida's objection, reversed the decision of the ALJ, and sustained the Commissioner's initial determination that Yoga Vida is liable for additional unemployment contributions. Yoga Vida appealed to the Appellate Division, which affirmed the determination of the Appeal Board, holding that "[o]verall, despite the existence of evidence that could result in a contrary result, the record contains substantial evidence to support the Board's decision that Yoga Vida had sufficient control over the instructors' work, thereby allowing for a finding of an employer-employee relationship" (119 AD3d 1314, 1315 [3d Dept 2014]). "[S]ubstantial evidence consists of proof within the whole record of such quality and quantity as to generate conviction in and persuade a fair and detached fact finder that, from that proof as a premise, a conclusion of ultimate fact may be extracted reasonably — probatively and logically" (300 Gramatan Ave. Assoc. v State of Div. of Human Rights, 45 NY2d 176, 181 [1978]). Here, because the record as a whole does not demonstrate "that the employer exercises control over the results produced and the means used to achieve the results" (Matter of Hertz Corp. [Commissioner of Labor], 2 NY3d 733, 735 [2004] [internal citation omitted]), the Board's determination that the company exercised sufficient direction, supervision and control over the instructors to demonstrate an employment relationship is unsupported by substantial evidence. The non-staff instructors make their own schedules and choose how they are paid (either hourly or on a percentage basis). Unlike staff instructors, who are paid regardless of whether anyone attends a class, the non-staff instructors are paid only if a certain number of students attend their classes. Additionally, in contrast to the staff instructors, who cannot work for competitor studios within certain geographical areas, the studio does not place any restrictions on where the non-staff teachers can teach, and the instructors are free to inform Yoga Vida students of classes they will teach at other locations so the students can follow them to another studio. Furthermore, only staff instructors, as distinct from non-staff instructors, are required to attend meetings or receive training. The proof of incidental control relied upon by the Board, including that Yoga Vida inquired if the instructors had proper licenses, published the master schedule on its web site, and provided the space for the classes, does not support the conclusion that the instructors are employees. Similarly, in this context, the evidence cited by the dissent, including that Yoga Vida generally determines what fee is charged and collects the fee directly from the students, and provides a substitute instructor if the non-staff instructor is unable to teach a class and cannot find a substitute, does not supply sufficient indicia of control over the instructors. Furthermore, that Yoga Vida received feedback about the instructors from the students does not support the Board's conclusion. "The requirement that the work be done properly is a condition just as readily required of an independent contractor as of an employee and not conclusive as to either" (Matter of Hertz Corp., 2 NY3d at 735 [internal citation and quotation marks omitted])."

Tuesday, February 21, 2017

CHILD CUSTODY - RELOCATION FROM ONE END OF LONG ISLAND TO THE OTHER

Many people in the New York metropolitan area colloquially refer to Long Island (the Nassau–Suffolk county area) as The Island. But The Island is the 11th largest island in the United States and the 149th-largest island in the world—larger than the 1,214 square miles of the smallest U.S. state, Rhode Island.

From Floral Park, New York to East Hampton is about 90 miles and over a 90 minute drive. So when one seeks to relocate but claims it is not a big relocation because they are remaining on The Island, there will be hurdles to pass as illustrated in DeFilippis v. DeFilippis, 2017 NY Slip Op 147 - NY: Appellate Div., 2nd Dept. 2017:

"The parties married and subsequently had two children. In 2014, the plaintiff commenced this action against the defendant for a divorce and ancillary relief. While the action was pending, the plaintiff sought to relocate with the children from Floral Park to East Hampton. The plaintiff contended that this relocation would enhance the children's lives economically, emotionally, and educationally. The defendant opposed the relocation, contending that if the children moved to East Hampton he would be unable to remain involved in their daily lives, school, or extracurricular activities, as he would see them only on the weekends. The Supreme Court granted the plaintiff's relocation motion, and the defendant appeals. We reverse.

When a parent seeks to relocate with a child, "this Court's authority is as broad as that of the hearing court, and a relocation determination will not be permitted to stand unless it is supported by a sound and substantial basis in the record" (Matter of Caruso v Cruz, 114 AD3d 769, 771-772). The parent seeking to relocate must "establish[ ] by a preponderance of the evidence that a proposed relocation would serve the child's best interests" (Matter of Tropea v Tropea, 87 NY2d 727, 741). Each case "must be considered on its own merits with due consideration of all the relevant facts and circumstances and with predominant emphasis being placed on what outcome is most likely to serve the best interests of the child" (id. at 739). Although the parents' rights are significant, the child's needs and rights "must be accorded the greatest weight," and the effect of the relocation on the noncustodial parent's relationship with the children "will remain a central concern" (id.). Additional relevant factors "include, but are certainly not limited to each parent's reasons for seeking or opposing the move, the quality of the relationships between the child and the custodial and noncustodial parents, the impact of the move on the quantity and quality of the child's future contact with the noncustodial parent, the degree to which the custodial parent's and child's life may be enhanced economically, emotionally and educationally by the move, and the feasibility of preserving the relationship between the noncustodial parent and child through suitable visitation arrangements" (id. at 740-741).

Here, the Supreme Court's determination that the plaintiff could relocate with the children was not supported by a sound and substantial basis in the record (see Matter of Caruso v Cruz, 114 AD3d at 772), as the plaintiff did not establish by a preponderance of the evidence that the proposed relocation would serve the children's best interests (see Matter of Tropea v Tropea, 87 NY2d at 741). The plaintiff's evidence that relocating would enhance her life and the children's lives economically was tenuous at best (see Rubio v Rubio, 71 AD3d 862, 863), and the court's finding that the plaintiff could become self-supporting and contribute to the children financially if she relocated was thus speculative and not supported by a sound and substantial basis in the record (see Matter of Caruso v Cruz, 114 AD3d at 772). Moreover, the relocation would negatively impact the quantity and quality of the children's future contact with the defendant, which weighs against granting relocation in this case (see Matter of Tropea v Tropea, 87 NY2d at 741). The defendant presented evidence of his involvement in the children's daily lives, school, and extracurricular activities. If the plaintiff was permitted to relocate with the children to East Hampton, the defendant would no longer be able to see the children midweek or remain involved in their many activities (see Quinn v Quinn, 134 AD3d 688, 689; Schwartz v Schwartz, 70 AD3d 923, 925; cf. Matter of DeCillis v DeCillis, 128 AD3d 818, 820). Finally, the plaintiff did not establish by a preponderance of the evidence that her proposed relocation would enhance the children's lives emotionally or educationally (see Matter of Tropea v Tropea, 87 NY2d at 741). Since the plaintiff did not meet her burden to demonstrate that relocating was in the children's best interests, we reverse the order granting relocation and deny the plaintiff's relocation motion."

Labels:

child custody,

divorce,

relocation

Monday, February 20, 2017

IS IT WASHINGTON'S DAY OR PRESIDENTS' DAY?

The Uniform Monday Holiday Act (Pub.L. 90–363) is an Act of Congress that amended the federal holiday provisions of the United States Code to establish the observance of certain holidays on Mondays. The Act was signed into law on June 28, 1968 and took effect on January 1, 1971. The official designation of the federal holiday observed on the third Monday of February is Washington’s Birthday. See section 6103(a) of title 5 of the United States Code.

New York Law is the same. General Construction Law § 24 provides: The term public holiday includes the following days in each year: "the first day of January, known as New Year's day; the third Monday of January known as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. day; the twelfth day of February, known as Lincoln's birthday; the third Monday in February, known as Washington's birthday; ......"

Friday, February 17, 2017

CHILD CUSTODY - TEENAGER'S PREFERENCE NOT CONTROLLING

MATTER OF MANELL v. MANELL, 2017 NY Slip Op 224 - NY: Appellate Div., 3rd Dept. 2017, where the child in question was the parties' 14/15 year old son:

"The father asserts that the child wishes to live primarily with him and have weekend parenting time with the mother. The attorney for the child concurs with the father's position, and further argues that, significantly, the child's wishes have not changed in the period since the trial determination. Although the child's desires are considered as part of the best interests analysis, they are "but one factor to be considered . . . [and] should not be considered determinative," and "the potential for influence having been exerted on the child" must also be considered (Eschbach v Eschbach, 56 NY2d 167, 173 [1982]; see Matter of Benjamin v Lemasters, 125 AD3d 1144, 1147 [2015]). Here, we note that the father's testimony reveals that he spoke to the child on at least four separate occasions regarding with whom he wanted to live. Contrary to the father's argument, we find that Family Court's decision reveals that it considered the child's wishes as part of its best interests analysis, although the request was not granted (see Matter of Rivera v LaSalle, 84 AD3d 1436, 1438 [2011]; Matter of Rutland v O'Brien, 143 AD3d 1060, 1062 [2016]).

Family Court found both parties to be fit and loving parents who are able to provide stable homes and cooperate regarding visitation and the child's needs and activities. The teenage child resides with the mother in his childhood home and continues to attend the same school that he has attended since pre-kindergarten. The child has regular contact with certain members of the mother's family who are her immediate neighbors. The father resides with the child's paternal grandparents, who have indicated that the father and the child may live at their residence as long as is necessary. The mother works part time and provides for someone else to be present for the child when necessary. The father works full time, but does not work on the weekends during his parenting time, and the child's grandparents are otherwise available to watch the child. Assistance with schoolwork and facilitation of the child's extracurricular activities are provided by both parents.

Family Court acknowledged the mother's history of alcoholism and found the mother's undisputed sobriety since November 2012 to be a laudable achievement. Regarding the mother's allegations of domestic violence, the court credited certain testimony by the father in concluding that the incidents did not result in any basis for finding him unfit for providing adequate moral guidance, and further found that these incidents had occurred solely in the past, prior to the parties' separation. In the absence of further altercations after the parties' separation, the record supports the finding that these incidents do not currently affect the best interests of the child.

Family Court found, and the record supports, that "the best interests of [the] child[] are served by a continuing relationship with both parents" (Matter of Bennett v Bennett, 208 AD2d 1042, 1042 [1994]; see Weiss v Weiss, 52 NY2d 170, 175 [1981]). In rendering the determination, the court specifically found that the mother has been "extremely cooperative" with the father, and "has not refused any requests for him to spend additional time with" the child. The testimony of both parties indicates that the mother has been the child's primary caretaker, whereas the father frequently participates in hunting and other outdoor activities with the child — activities which Family Court found to be an "integral part of [the child's] identity." The mother testified that she only occasionally participates in outdoor activities with the child. In light of the parties' distinct roles in their child's life, we cannot find that the determination failed to balance the time shared with the two parents in an appropriate manner. Family Court's order acknowledged the child's history of outdoor activities with the father, while also recognizing a need to "ensure that the mother's relationship with the child will be promoted and preserved." Under these circumstances, we find the award of primary weekday custody to the mother with substantial weekend parenting time to the father to be supported by a sound and substantial basis in the record, and we will not disturb it (see Matter of Lawton v Lawton, 136 AD3d at 1169; Matter of Holland v Klingbeil, 118 AD3d 1077, 1079 [2014]; Matter of Gordon v Richards, 103 AD3d 929, 931 [2013])."

Labels:

child custody,

child visitation,

teenagers

Thursday, February 16, 2017

PREPARING FOR AN UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE HEARING

The New York State Unemployment Insurance Appeal Board has released a video: "Preparing for Your Unemployment Insurance Hearing"

See http://uiappeals.ny.gov/ui-appeal-board-frequently-asked-questions.shtm?direct-link=video-preparing-for-unemployment-insurance-hearing

Labels:

Hearings,

Unemployment Insurance

Wednesday, February 15, 2017

ON THE COMMERCIAL DIVISION OF NEW YORK STATE SUPREME COURT

"A Forum

for Business Disputes: The Commercial Division of the Supreme Court of the

State of New York" - Chief Judge

DiFiore and a number of other Judges, lawyers and General Counsel of major

corporations comment ont the Commercial Division of the New York State

Supreme Court.

Labels:

Business,

Commercial Cases,

New York Supreme Court

Tuesday, February 14, 2017

A DISCUSSION ON THE RIGHT OF PARTITION

ZARBIS v. TRIADES, 2015 NY Slip Op 30317 - NY: Supreme Court 2015:

"The ancient remedies of actual partition, and of partition and sale are premised in equity and are now codified in Article 9 of the Real Property Actions and Proceedings Law (see Chang v Chang, 137 AD2d 371, 529 NYS2d 294 [1st Dept 1988]; Worthing v Cossar, 93 AD2d 515, 462 NYS2d 920 [4th Dept 1983]; Grody v Silverman, 222 AD 526, 226 NY 468 [1928]). Under RPAPL § 901, "a person holding and in possession of real property as a joint tenant or tenant in common, in which he [or she] has an estate of inheritance, or for life, or for years, may maintain an action for the partition of the property, and for a sale if it appears that a partition cannot be made without great prejudice to the owners" (RPAPL § 901[1]; Tsoukas v Tsoukas, 107 AD3d 879, 968 NYS2d 109 [2d Dept 2013]). Accordingly, one owning an interest in real property with a right of possession such as a tenant, joint tenant or a tenant in common may seek physical partition of the property, or, a partition and sale thereof, if it appears that physical partition alone would greatly prejudice the owners of the premises (see Cadle Co. v Calcador, 85 AD3d 700, 926 NYS2d 106 [2d Dept 2011]; Bufogle v Greek, 152 AD2d 527, 528, 543 NYS2d 152 [2d Dept 1989]; see also Arata v Behling, 57 AD3d 925, 870 NYS2d 450 [2d Dept 2008]; Wilbur v Wilbur, 266 AD2d 535, 699 NYS2d 103 [2d Dept 1999]). While an accounting is a necessary incident of a partition action and should be had as a matter of right before entry of an interlocutory or final judgment and before any division of money between the parties is adjudicated (see Sampson v Delane, 34 AD3d 349, 824 NYS2d 277 [1st Dept]; Donlon v. Diamico, 33 AD3d 841, 823 NYS2d 483 [2d Dept 2006]; McVicker v Sarma, 163 AD2d 721, 558 NYS2d 997 [2d Dept 1990]; Worthing v Cossar, 93 AD2d 515, 462 NYS2d 920 [2d Dept [1983]), a sale without an accounting is permissible in cases wherein no accounting is demanded nor any claims for an adjustment of the rights of any party due to receipt by one party of more than his or her proper proportion of the rents, profits or share interest in the premises are asserted (see Robert McCormick v Pickert, 51 AD3d 1109, 856 NYS2d 306 [2d Dept 2008]).

In the absence of an agreement against partition, a partition of real property owned by joint tenants or tenants in common is a matter of right whenever one or more of them do not wish to hold and use the property under their tenancies (see Smith v. Smith, 116 AD2d 810, 497 NYS2d 19 [3d Dept 1986]; Gasko v Del Ventura, 96 AD2d 896, 466 NYS2d 64 [2d Dept 1983]; Chew v Sheldon, 214 NY 344, 108 NY 522 [1915]). This right to the remedy of partition has been long recognized as a "valuable part of such interest in that it affords the owner a means of disposing of his interest which cannot be defeated by his co-owners" (Rosen v Rosen, 78 AD2d 911, 912, 432 NYS2d 921 [3d Dept 1989]). The right to partition is not absolute, however, and while a tenant in common or joint teneant has the right to maintain an action for partition pursuant to RPAPL 901, the remedy is always subject to the equities between the parties (see Tsoukas v Tsoukas, 107 AD3d 879, supra; Pando v Tapia, 79 AD3d 993, 995, 914 NYS2d 226 [2d Dept 2010]; Arata v Behling, 57 AD3d 925, 926, 870 NYS2d 450 [2d Dept 2008]; Graffeo v Paciello, 46 AD3d 613, 614, 848 NYS2d 264 [2d Dept 2007]).

Before a partition or sale may be directed, a determination must be made as to the rights, shares, or interests of the parties and, in those cases wherein a sale is demanded rather than an actual physical partition, whether the property or any part thereof is so circumstanced that a partition thereof cannot be made without great prejudice to the owners (see RPAPL § 915). Such determinations must be included in the interlocutory judgment contemplated by RPAPL § 915 along with either a direction to sell at public auction or a direction to physically partit on the premises (see RPAPL § 911; § 915; Hales Ross, 89 AD3d 1261, 932 NYS2d 263 [2d Dept 2011]; see also Lauriello v Gallotta, 70 AD3d 1009, 895 NYS2d 495 [2d Dept 2010]; Wolfe v Wolfe, 187 AD2d 628, 590 NYS2d 504 [2d Dept 1992]). Determinations of the rights and shares of the parties must be made by declaration of the court directly or after a reference to take proof and report (see RPAPL § 911; § 907; Mary George, D.M.D. & Ralph Epstein, D.D.S., P.C. v J. William, 113 AD2d 869, 493 NYS2d 794 [2d Dept 1985]; see also Colley v Romas, 50 AD3d 1338, supra). Inquiry and ascertainment by the court or by reference into the existence of creditors having liens or other interest in the premises is also required and, if there be any such creditors, proceedings thereon must be held as required by RPAPL § 913. While the court may accept proof of the absence of the existence of any such creditor and dispense with the reference and the proceedings required thereon, a finding to that effect should issue.

The law is clear that in order to maintain an action for partition the plaintiff or other claimant must be the owner of an interest in real property and have legal title thereto or to a part thereof (see Sealy v Clifton, LLC, 68 AD3d 846, 890 NYS2d 598 [2d Dept 2009]; Mohamed v Defrin, 45 AD3d 252, 844 NYS2d 265 [1st Dept 2007]; Garland v Raunheim, 29 AD2d 383, 288 NYS2d 417 [1st Dept 1968]; Gifford v Whittemore, 4 AD2d 379, 165 NYS2d 201 [3d Dept 1957]; Harvey v Metz, 271 AD 788, 65 NYS2d 85 [2d Dept 1946]; O'Connor v O'Connor, 249 AD 515, 293 NYS 64 [2d Dept 1937]; McGillivray v Brundage, 36 Misc.2d 106, 231 NYS2d 870 [Sup. Ct. Monroe Cty. 1962]; Fraser v Bowerman, 104 Misc. 260, 171 NYS 835 [Sup Ct. Niagra Cty. 1918), aff'd. 187 AD 926, 174 NYS 903 [4th Dept 1919]). It is equally clear that a person who is possessed of an enforceable right to a conveyance of an interest in real property, but who is without legal title to such property, has no cognizable claim for partition (see Side v Brenneman, 7 AD 273, 40 NYS 3 [1st Dept 1896]).

Viable claims for partition and sale must thus rest upon allegations of a joint or common ownership in real property with attendant rights to possession and that the equities favor the claimant and, where a sale rather than an actual partition is demanded, proof that a physical partition of the premises cannot be made without great prejudice to the parties is also required (see Galitskaya v Presman, 92 AD3d 637, 937 NYS2d 878 [2d Dept 2012]; Cadle Co. v Calcador, 85 AD3d 700, supra; James v James, 52 AD3d 474, 859 NYS2d 479 [2d Dept 2008]). An award of summary judgment on a claim for partition is established only where the movant demonstrates its ownership interest and a right to possession under a deed or other instrument of conveyance, favorable equities and that a physical partition cannot be made without great prejudice in cases wherein a sale is demanded (see Tsoukas v Tsoukas, 107 AD3d 879, supra, Arata v Behling, 57 AD3d 925, 870 NYS2d 450 [2d Dept 2008])."

Labels:

Partition,

Real Estate

Monday, February 13, 2017

TENANTS LIVING IN PREMISES THAT ARE BEING FORECLOSED

This is from the New York Courts website:

"When the plaintiff starts a foreclosure case against the owner of your home, the law says that the plaintiff must tell the tenants within 10 days. You may find out about the case by seeing a notice posted on the door to your building or the plaintiff may give you a copy of the foreclosure Summons and Complaint. Do not worry if your name is on the papers. This does not mean that you have to move out. Many things can happen:

•The owner may settle the case and keep the property

•The bank may not be able to prove its case

•The case may take a very long time, often even a year, and you may move before it is over

•The new owner may want to keep you as a tenant

•You may have the right to stay anyway

The point is, you don’t have to do anything right now.

During the foreclosure case, the owner is still in charge of keeping your home or apartment in livable condition and still collects rent and can start a case in Court against you. But, you can’t be evicted without a court order.

Whoever buys the building at a foreclosure sale can’t make you move out right away. The law says that the new owner (or the bank if the bank still owns the building) has rules to follow if the new owner wants to evict you. Whether the new owner wants to evict you or not, you should get a notice from the new owner. After the sale, you have to pay your rent to the new owner."

For more help or information, see https://www.nycourts.gov/courthelp/Homes/foreclosureTenants.shtml

Friday, February 10, 2017

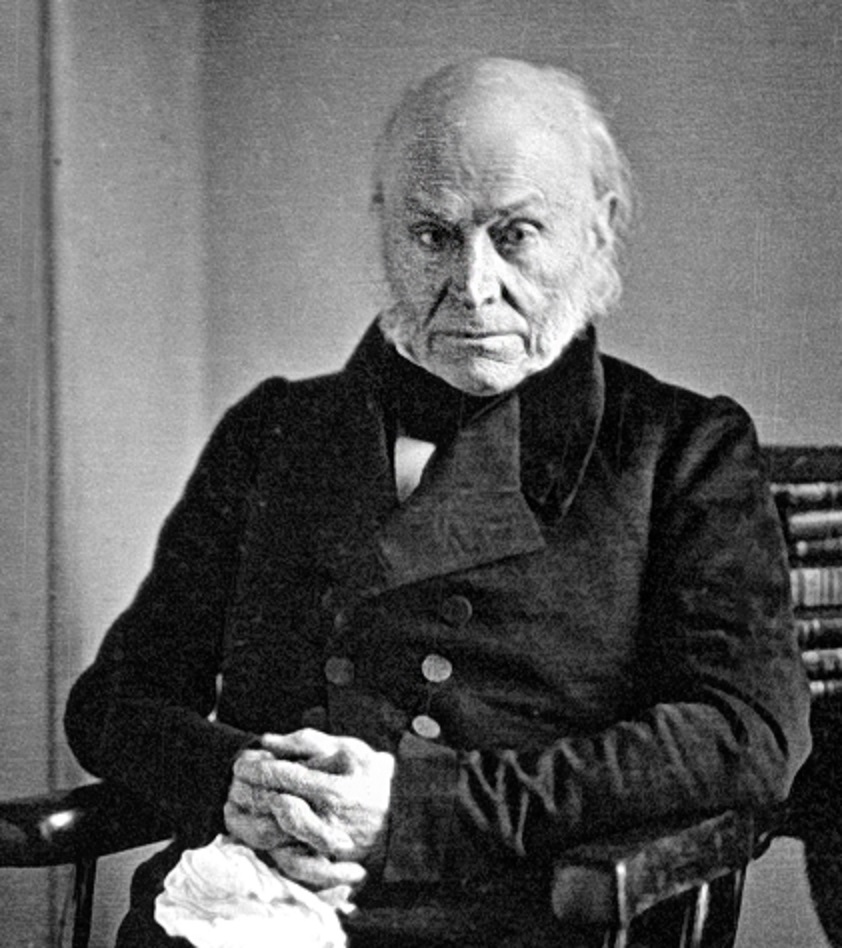

LAW - SOME HISTORY

In February 1840, former President John Quincy Adams began his oral arguments in front of the U.S. Supreme Court in United States v. Amistad.

Adams spoke to the court highlighting that it was a part of the judicial branch and not part of the executive. He introduced copies of correspondence between the Spanish government and the Secretary of State and criticized President Martin Van Buren for his assumption of unconstitutional powers in the case:

"This review of all the proceedings of the Executive I have made with utmost pain, because it was necessary to bring it fully before your Honors, to show that the course of that department had been dictated, throughout, not by justice but by sympathy – and a sympathy the most partial and injust. And this sympathy prevailed to such a degree, among all the persons concerned in this business, as to have perverted their minds with regard to all the most sacred principles of law and right, on which the liberties of the United States are founded; and a course was pursued, from the beginning to the end, which was not only an outrage upon the persons whose lives and liberties were at stake, but hostile to the power and independence of the judiciary itself"

Thursday, February 9, 2017

Wednesday, February 8, 2017

ACTIONS AGAINST UNLICENSED CONTRACTORS

The rules differ somewhat in the First and Second Department. This was discussed recently in MATTER OF MacNAMARA v. Edwards, 2016 NY Slip Op 32199 - NY: Supreme Court 2016:

"The established law of the Second Department is clear that a home improvement contractor who is unlicensed at the time of the performance of the work for which he or she seeks compensation forfeits the right to recover damages based on either breach of contract or quantum meruit (Flax v. Hommel, 40 AD3d 809, 810, 835 NYS2d 735, 736 [2d Dept. 2007]; accord Emergency Restoration Servs. Corp. v. Corrado, 109 AD3d 576, 577, 970 NYS2d 806, 807 [2d Dept. 2013][applying Suffolk County Code regulating unlicensed home improvement]; Racwell Const., LLC v. Manfredi, 61 AD3d 731, 732-33, 878 NYS2d 369, 371 [2d Dept. 2009][Westchester County]). Pursuant to CPLR 3015(e), a complaint that seeks to recover damages for breach of a home improvement contract or to recover in quantum meruit for home improvement services is subject to dismissal . . . if it does not allege compliance with the licensing requirement" (CMC Quality Concrete III, LLC v. Indriolo, 95 AD3d 924, 925-26, 944 NYS2d 253, 254-55 [2d Dept. 2012]).

Generally speaking the law of this department recognizes that a homeowner may seek restitution for payments actually made for work which was not performed or for defective work (Brite-N-Up, Inc. v. Reno, 7 AD3d 656, 657, 776 NYS2d 839, 840 [2d Dept. 2004]; Goldstein v. Gerbano, 158 A.D.2d 671, 552 N.Y.S.2d 44, 45 [2d Dept. 1990] [plaintiffs were entitled to rescind the contracts and to recover the amounts designated in the judgment as a result of the defendant's failure to perform]; Segrete v. Zimmerman, 67 AD2d 999, 1000, 413 NYS2d 732, 733 [2d Dept. 1979]; compare with Sutton v. Ohrbach, 198 AD2d 144, 144, 603 NYS2d 857, 857 [1st Dept. 1993][plaintiff may not use the statute as a sword to recoup monies already paid in exchange for the purportedly unlicensed services])."

Tuesday, February 7, 2017

WHEN DIVORCED PARENTS DO NOT AGREE ON ADHD TREATMENT

A few years ago the New York Times reported that "the zeal to find and treat every A.D.H.D. child has led to too many people with scant symptoms receiving the diagnosis and medication. The disorder is now the second most frequent long-term diagnosis made in children, narrowly trailing asthma, according to a New York Times analysis of C.D.C. data." Certainly, the question of "to medicate or not" can be an issue with divorced parents. Such was the case in MATTER OF ANDREA C. v. David B., 2017 NY Slip Op 223 - NY: Appellate Div., 3rd Dept. 2017:

"Petitioner (hereinafter the mother) and respondent (hereinafter the father) are the divorced parents of a daughter (born in 2005). In June 2007, the parties stipulated to an order granting them joint legal custody of the child with primary physical placement to the mother and specified visitation to the father[1]. Although the parties thereafter expanded the father's visitation schedule on their own accord and, together with the father's new wife, often shared family dinners together, a growing disagreement began brewing between the mother and the father with respect to, among other things, day care arrangements for the child, her participation in various summer or holiday camps and the individualized services that were provided to her[2]. The parties' differences came to a head in 2013 when the mother had the child evaluated for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (hereinafter ADHD) and a recommendation was made that the child receive a combination of medication and counseling; the mother "was very interested in doing a trial of medication" while the father "was totally against doing any medication."

Insofar as is relevant here, the mother commenced the first of these proceedings in September 2014 seeking sole custody of the child — citing, among other things, the father's lack of cooperation and interference with the child's service providers. The father cross-petitioned for sole custody — asserting, among other things, that the mother lacked the ability to effectively manage the child's behavioral issues and placed the child on ADHD medication without his consent — and also filed a violation petition alleging that the mother failed to adhere to the visitation schedule set forth in the June 2007 order. A lengthy fact-finding hearing ensued, during the course of which testimony was received from, among others, numerous service providers, counselors and school officials. Following a Lincoln hearing, Family Court issued a comprehensive and well-reasoned decision detailing, among other things, the parties' respective parental strengths and shortcomings, their level of acknowledgment of and philosophical differences regarding the appropriate treatment governing their daughter's disabilities, their respective abilities to engage and work in a cooperative fashion with the child's service providers, the quality of their respective home environments and their individual abilities to provide for their child's intellectual and emotional development. Upon due consideration thereof, Family Court awarded the mother sole legal and physical custody of the child with significant visitation to the father. This appeal by the father ensued.[3]

Initially, the father does not dispute that the marked deterioration in the parties' relationship and their corresponding inability and/or unwillingness to work with one another in a cooperative fashion for the sake of their child constitutes a change in circumstances for purposes of satisfying the mother's initial burden on her modification petition (see Matter of Rockhill v Kunzman, 141 AD3d 783, 784 [2016]). For those same reasons, there also is no question that joint legal custody no longer is feasible (see Matter of Zahuranec v Zahuranec, 132 AD3d 1175, 1176 [2015]). Hence, Family Court was tasked with fashioning a custodial arrangement that would best serve the child's interests. Upon reviewing the record as a whole and giving due consideration to all of the relevant factors, including "each parent's ability to furnish and maintain a suitable and stable home environment for the child, past performance, relative fitness, ability to guide and provide for the child's overall well-being and willingness to foster a positive relationship between the child and the other parent" (Matter of Bailey v Blair, 127 AD3d 1274, 1276 [2015] [internal quotation marks, brackets and citations omitted]; see Matter of Coleman v Millington, 140 AD3d 1245, 1247 [2016]), as well as the transcript of the Lincoln hearing (see Matter of Shokralla v Banks, 130 AD3d 1263, 1265 [2015]), we are satisfied that Family Court's decision to award sole legal and physical custody of the child to the mother and expansive visitation to the father is supported by a sound and substantial basis in the record.

Here, Family Court was faced with the difficult task of choosing between two loving but very different (and often obstinate) parents — each of whom possesses largely irreconcilable parenting philosophies (particularly with respect to their appreciation of and willingness to seek outside help with respect to their child's particular needs). According to the father, the mother lacks the intellectual capacity and coping skills to properly manage and resolve the child's behavioral issues, has effectively delegated her parental decision making to various third-party service providers and has demonstrated impaired parental judgment by excluding him from important decisions regarding the child's care and treatment. The mother, on the other hand, contends that the father refuses to accept the child's disabilities, does not support the recommended treatment for the child's diagnosed ADHD, is opposed to the child's enrollment in special education classes (preferring instead that she "act like a regular child") and has effectively abdicated his parental role by, among other things, failing to pursue needed services for the child — believing instead that he alone is capable of meeting her needs. Family Court, drawing upon its "superior vantage point of observing the demeanor of the witnesses who testified before it" (Matter of Ryan v Lewis, 135 AD3d 1135, 1137 [2016] [internal quotation marks and citation omitted]), largely credited the testimony of the mother — finding that the mother was "more aware of and involved with" the child's teachers and service providers, had made "thoughtful, rational[] decisions" with respect to the child's welfare and, on balance, was capable of providing "a greater continuity of care" for the child than the father (see Matter of Blagg v Downey, 132 AD3d 1078, 1080 [2015]). The court's findings in this regard are fully supported by the testimony of numerous service providers, who generally attested to the father's lack of involvement in, opposition to and/or disruptive behavior regarding their efforts to provide services to the child (see Matter of Virginia C. v Donald C., 114 AD3d 1032, 1034 [2014]). Although Family Court recognized the "important role" that the father played in the child's life, including providing necessary structure and discipline, it was, in the final analysis, the father's attitude, demeanor and parenting style that prompted Family Court to award sole legal and physical custody to the mother — taking care to ensure that the father had frequent and meaningful access to the child and, further, that he was kept apprised of the child's medical and service providers and received appropriate notices and updates from the child's school. Given that Family Court had the opportunity to observe the parties and their respective witnesses firsthand over the course of the lengthy fact-finding hearing, and inasmuch as the court's findings are supported by a sound and substantial basis in the record, we discern no basis upon which to disturb the custodial arrangement fashioned by Family Court. The father's remaining contentions are either unpreserved for our review or have been examined and found to be lacking in merit.

[1] The June 2007 order apparently was incorporated but not merged into the parties' 2009 judgment of divorce.

[2] The child, who has certain learning disabilities and developmental delays, began receiving early intervention services as an infant and, as of the time of the hearing, had an individualized education plan.

[3] During the pendency of this appeal, the parties filed competing modification petitions, in addition to certain enforcement and violation petitions. By order entered August 17, 2016, Family Court, among other things, dismissed the respective modification petitions, declining to alter the custodial arrangement set forth in its September 2015 order. Accordingly, this appeal is not moot."

Labels:

Child care,

child custody,

Special Needs

Monday, February 6, 2017

MORTGAGE FORECLOSURE CLINIC TODAY

Today, Newsday reports: "A network of housing agencies and legal groups that has helped more than 20,000 Long Islanders facing foreclosure is pushing to get funding for its work included in next year’s state budget.The groups — including 15 Long Island organizations — are due to lose funding in September if they do not receive state support..."

One these groups is the Nassau County Bar Association. I will be volunteering today, Monday February 6, at the Nassau County Bar Association's free clinic for Mortgage Foreclosure, Bankruptcy and Superstorm Sandy issues, from 3pm to 6pm.

For more information, contact Nassau County Bar Association, 15th and West Streets, Mineola, NY 11501 at (516) 747-4070

Friday, February 3, 2017

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE - NEW TOOL IN SUFFOLK COUNTY

Newsday reports:

"Victims of domestic violence seeking temporary orders of protection in Suffolk can submit requests electronically and speak to judges via video conference under a new program, officials said Thursday. With the help of advocates and attorneys, individuals who suffer from domestic abuse can ask for orders of protection from remote sites, including shelters, hospitals, senior centers, and the First Precinct in West Babylon."

Labels:

Domestic Violence,

E filing,

Order of Protection

Thursday, February 2, 2017

SMALL CLAIMS COURT NOT AVAILABLE DUE TO FEDERAL ARBITRATION LAW

Johnson v. ACE HOME INSPECTIONS OF UPSTATE NEW YORK, 2017 NY Slip Op 50075 - NY: City Court 2017:

"This matter arises out of the Court's small claims jurisdiction (Uniform City Court Act § 1802). On August 7, 2015, Johnson entered into a home inspection agreement with Ace Home Inspections of Upstate New York. Johnson alleged that Ace failed to notice a defect in her roof that later manifested itself by leaking water into her home. She seeks damages in the amount of $600. At the commencement of the trial, Ace moved the Court to compel arbitration under the auspices of the Inspection Agreement (exhibit A). Under the heading of dispute resolution, the agreement contains the following clause: "In matters of dispute, the `client' agrees to submit to binding arbitration by mutually agreed upon party(s) [sic]" (id.).

Both state and federal law place mandates upon a court to compel arbitration under the appropriate circumstances. Initially the Court turns to New York law. CPLR 7503[1] provides:

A written agreement to submit any controversy thereafter arising or any existing controversy to arbitration is enforceable without regard to the justiciable character of the controversy and confers jurisdiction on the courts of the state to enforce it and to enter judgment on an award.The Court finds CPLR 7503 inapplicable. Small claims jurisdiction provides an affordable forum for litigants to resolve claims based upon substantial justice (see Carlo v Koch-Matthews, 53 Misc 3d 466, 470 [City Ct 2016]). The Legislature granted unique access to the courthouse and once a statute so opens the courthouse door, it is not easily closed by contract. In Licitra v Gateway, Inc., 189 Misc 2d 721, 728 [City Ct 2001], the court held "the defendant cannot by `contract' deny access to small claims court without a specific and agreed-to written waiver by the consumer." In others words, for an arbitration clause to eradicate small claims jurisdiction, the parties must explicitly waive the right to proceed in small claims court. That did not happen here — the clause has no effect — at least under New York law.

While precedent neatly resolves the state issue, the federal issue is not so effortlessly disposed of (see generally David D. Siegel, McKinney's Cons Law of NY, Book 29A, UCCA §1801,2002 Practice Commentary [while noting that small claims jurisdiction is not superseded by state law, the federal issue is not addressed]). The Federal Arbitration Act ("FAA") (9 U.S.C. § 2) provides:

A written provision in any contract evidencing a transaction involving commerce to settle by arbitration a controversy thereafter arising out of such contract or transaction . . . shall be valid, irrevocable, and enforceable, save upon such grounds as exist at law or in equity for the revocation of any contract.To begin with, the Court cannot simply conclude that small claims matters trump the FAA. In a brigade of cases, the Supreme Court has made it unrelentingly clear that when state law prohibits outright the arbitration of a particular type of claim (like small claims), the analysis is straightforward: The conflicting rule is displaced by the FAA (AT & T Mobility LLC v. Concepcion, 563 U.S. 333 [2011]; Marmet Health Care Ctr., Inc. v. Brown, ___ U.S. ___ 132 S. Ct. 1201 [2012]; CompuCredit Corp. v. Greenwood, ___ U.S. ___ 132 S. Ct. 665 [2012]; Am. Exp. Co. v. Italian Colors Rest., ___ U.S. ___, 133 S. Ct. 2304 [2013]; Nitro-Lift Techs., L.L.C. v. Howard, ___ U.S. ___, 133 S. Ct. 500 [2012]; DIRECTV, Inc. v. Imburgia, ___ U.S. ___, 136 S. Ct. 463 [2015]).

The FAA, by its terms, applies only to transactions involving commerce. Consequently, the Court is left to inquire whether a home inspection involves interstate commerce. Congress' regulatory power extends to "those activities having a substantial relation to interstate commerce, . . . i.e., those activities that substantially affect interstate commerce" (United States v. Lopez, 514 U.S. 549, 558-559 [1995]). The Supreme Court has held that activities that "substantially affect" commerce may be regulated so long as they substantially affect interstate commerce in the aggregate, even if their individual impact on interstate commerce is minimal (see Wickard v. Filburn, 317 U.S. 111, 125 [1942] [holding that "even if appellee's activity be local and though it may not be regarded as commerce, it may still, whatever its nature, be reached by Congress if it exerts a substantial economic effect on interstate commerce"]). Here the inspection facilitates the home's purchase and without a doubt such activity affects commerce.

Although, the FAA creates no exceptions for small claims,[1] under the particular circumstances of this case to enforce arbitration is to enforce absurdity. The cost of arbitration is prohibitive in relationship to the amount of Johnson's claim. Johnson must spend thousands of dollars to recover hundreds — she cannot win. Where the fee to arbitrate exceeds the maximum possible recovery, such clauses perpetrate an irreconcilable injustice — compelling arbitration in this case does not seem fair.

Nevertheless, while this Court may express its disagreement with an Act of Congress or a decision of the United States Supreme Court, it may not dissociate itself from federal law. The FAA is the law of the United States and must be faithfully adhered to (U.S. Const., Art. VI, cl. 2 ["The Judges in every State shall be bound" by "the Laws of the United States"]). It is the Court's hope, however, that the Congress will see fit to exempt small claims actions from the inflexible reins of the FAA. Until then however, the FAA controls. Arbitration will be compelled.

[1] There is a doctrine, the effective vindication doctrine, which is designed "to prevent [the] prospective waiver of a party's right to pursue statutory remedies," Italian Colors Rest., ___ U.S. at ___, 133 S Ct at 2310 (internal quotations and citations omitted). Johnson can find no relief under this doctrine. First, Johnson does not seek the invocation of a right created by statute; this is a common law contract case. Rather she seeks to invoke a forum, albeit one created by statute. The opening of a forum equates not with a substantive statutory right. Second, doctrine cannot be employed simply because it is not "economically feasible" for a plaintiff to enforce a statutory right individually (Id. at 2311 n. 4 [emphasis omitted]). Indeed, the Supreme Court has noted that "the fact that it is not worth the expense involved in proving a statutory remedy does not constitute the elimination of the right to pursue that remedy" (Id. at 2311) (emphasis in the original)."

Labels:

Arbitration,

Small Claims

Wednesday, February 1, 2017

PROTECTING THE RIGHT TO COMPLAIN

On December 14, 2016, President Obama signed into effect the “Consumer Review Fairness Act of 2016” (the “Act”), making it more difficult for businesses to bring lawsuits over negative reviews.

From the House Report:

"This bill makes a provision of a form contract void from the inception if it: (1) prohibits or restricts an individual who is a party to such a contract from engaging in written, oral, or pictorial reviews, or other similar performance assessments or analyses of, including by electronic means, the goods, services, or conduct of a person that is also a party to the contract; (2) imposes penalties or fees against individuals who engage in such communications; or (3) transfers or requires the individual to transfer intellectual property rights in review or feedback content (with the exception of a nonexclusive license to use the content) in any otherwise lawful communications about such person or the goods or services provided by such person.

A "form contract" is a contract with standardized terms: (1) used by a person in the course of selling or leasing the person's goods or services, and (2) imposed on an individual without a meaningful opportunity to negotiate the standardized terms. The definition excludes an employer-employee or independent contractor contract.

The standards under which provisions of a form contract are considered void under this bill shall not be construed to affect:

- legal duties of confidentiality;

- civil actions for defamation, libel, or slander; or

- a party's right to establish terms and conditions for the creation of photographs or video of such party's property when those photographs or video are created by an employee or independent contractor of a commercial entity and are solely intended to be used for commercial purposes by that entity.

A provision shall not be considered void under this bill to the extent that it prohibits disclosure or submission of, or reserves the right of a person or business that hosts online consumer reviews or comments to remove, certain: (1) trade secrets or commercial or financial information; (2) personnel and medical files; (3) law enforcement records; (4) content that is unlawful or that a party has a right to remove or refuse to display; or (5) computer viruses or other potentially damaging computer code, processes, applications, or files.

A person is prohibited from offering form contracts containing a provision that is considered void under this bill."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)