Friday, September 29, 2017

Thursday, September 28, 2017

SPOUSAL MAINTENANCE INCLUDED IN INCOME FOR CHILD SUPPORT PURPOSES

Was this a drafting error or the actual intention of the parties? Note that the remand appears to require a hearing on the intention of the parties as the Supreme Court's determination was "as a matter of law".

Toscano v Toscano, 2017 NY Slip Op 06674, Decided on September 27, 2017, Appellate Division, Second Department:

"The parties, who have two children together, entered into a separation agreement dated September 9, 2011, which was incorporated, but not merged, into their subsequent judgment of divorce. In relevant part, the agreement provided that the plaintiff (hereinafter the mother) would pay the defendant (hereinafter the father) $4,000 per month in spousal support for 36 months, at which point the mother's spousal support obligation would decrease to $2,083.33 per month for 24 months, and then cease altogether.

The agreement also provided that, given the father's lack of any income in the year preceding separation, his child support obligation would be set at $25 per month. However, the agreement further provided that, upon the happening of any "adjustment circumstances" outlined in the agreement, the amount of the father's child support obligation would be adjusted using the statutory formula set forth in the Child Support Standards Act. Those circumstances were defined as: "(i) December 31st of any year in which the Father's earned income exceeds $25,000; (ii) December 31st of any year in which the Father's gross income from all sources exceeds $45,000; (iii) The date on which each child becomes emancipated." The agreement noted, however, that a court could modify any order of child support, including an order incorporating without merging an agreement or stipulation of the parties, upon a showing of (i) a substantial change of circumstances; (ii) three years having passed since the order was entered, last modified, or adjusted; or (iii) a change in either party's gross income by 15% or more since the order was entered, last modified, or adjusted.

By an order to show cause dated January 13, 2015, the mother moved, inter alia, to modify the father's child support obligation. In her supporting affidavit, the mother averred that, during the 2012 calendar year, she paid $48,000 in spousal support to the father, and thus, for that year, the father's "gross income from all sources" exceeded $45,000, triggering a mandatory adjustment of the father's basic child support obligation. The father, in opposition, contended that there was no indication in the agreement that the spousal support paid to him was intended to be included in the calculation of his child support obligation and that it was illogical that he would accept spousal support from the mother, only to immediately pay her back with her own money.

The Supreme Court concluded that the parties' agreement did not intend for child support to be paid back to the mother by the father from the spousal support she paid to him. The court stated that, if such was the parties' intention, the agreement would have clearly so stated, but that the court could not now construe the agreement as providing that the spousal support was to be considered income for child support purposes. In light of this determination, the court denied that branch of the mother's motion which was to modify the father's child support obligation. The mother appeals from so much of the order as denied that branch of her motion. We reverse the order insofar as appealed from.

A stipulation of settlement entered into by parties to a divorce proceeding constitutes a contract between them subject to the principles of contract interpretation (see Matter of Miller v Fitzpatrick, 147 AD3d 845; Ayers v Ayers, 92 AD3d 623, 624; De Luca v De Luca, 300 AD2d 342). Where the intention of the parties is clearly and unambiguously set forth, effect must be given to the intent as indicated by the language used (see Slatt v Slatt, 64 NY2d 966, 967; Matter of Miller v Fitzpatrick, 147 AD3d at 847; Ayers v Ayers, 92 AD3d at 624). "A court may not write into a contract conditions the parties did not insert by adding or excising terms under the guise of construction, and it may not construe the language in such a way as would distort the contract's apparent meaning" (Cohen-Davidson v Davidson, 291 AD2d 474, 475; see Matter of Scalabrini v Scalabrini, 242 AD2d 725, 726).

The Supreme Court erred in concluding that the parties did not intend to include the spousal support paid by the mother to the father as part of the father's gross income from all sources used to determine whether his child support obligation should be modified. The use of the terms "gross income from all sources," each of which have a clear and plain meaning in and of themselves, coupled with the fact that the agreement distinguished between "earned income" and "gross income from all sources," established that the parties contemplated a clear distinction between income the father earned and monies the father obtained from any sources, including spousal support, to support himself. Moreover, by concluding as it did, the court failed to acknowledge that the agreement specifically stated that the father would be required to report the spousal support as income on his tax returns, which, in fact, he did. The Child Support Standards Act requires the court to establish the parties' basic child support obligation as a function of the "gross (total) income" that is, or should have been, reflected on the most recently filed income tax return (Family Ct Act § 413[1][b][5][i]; see Matter of Krukenkamp v Krukenkamp, 54 AD3d 345; Miller v Miller, 18 AD3d 629, 631; Bains v Bains, 308 AD2d 557, 559; McNally v McNally, 251 AD2d 302, 303). Thus, the parties knew or should have known that the spousal support would be considered income to the father by any court called upon to modify his child support obligation. Ultimately, given the precise language utilized in the agreement, the court erred in concluding that the parties did not intend to include the father's spousal support in his gross income from all sources as a matter of law.

Accordingly, the order must reversed insofar as appealed from and the matter remitted to the Supreme Court, Suffolk County, for a new determination of that branch of the mother's motion which was to modify the father's child support obligation that includes spousal support received by the father in the calculation of his gross income from all sources."

Wednesday, September 27, 2017

HOME IMPROVEMENT CONTRACTORS - NO SIGNED WRITTEN AGREEMENT

HOME CONSTRUCTION CORP. v. BEAURY, 2017 NY Slip Op 2628 - NY: Appellate Div., 2nd Dept. 2017 where plaintiff claimed the total cost of the project, including additions and credits, was $1,068,720, of which $219,850 remained unpaid:

"General Business Law § 771 sets forth a number of requirements for home improvement contracts, including that the contract be evidenced by a writing signed by all the parties to the contract (see General Business Law § 771; Johnson v Robertson, 131 AD3d 670, 672; Evans-Freke v Showcase Contr. Corp., 85 AD3d 961, 962). Generally, the absence of an enforceable written agreement between the parties precludes a contractor from recovering for breach of a home improvement contract (see F & M Gen. Contr. v Oncel, 132 AD3d 946, 948; Johnson v Robertson, 131 AD3d at 672; Frank v Feiss, 266 AD2d 825, 826; Mindich Devs. v Milstein, 227 AD2d 536, 536-537).

Although a contractor cannot enforce a contract that fails to comply with General Business Law § 771, a contractor may seek to recover based on the equitable theory of quantum meruit (see Johnson v Robertson, 131 AD3d at 672; Evans-Freke v Showcase Contr. Corp., 85 AD3d at 962; Frank v Feiss, 266 AD2d at 826; Mindich Devs. v Milstein, 227 AD2d at 537). "The elements of a cause of action sounding in quantum meruit are (1) performance of services in good faith, (2) acceptance of services by the person to whom they are rendered, (3) expectation of compensation therefor, and (4) reasonable value of the services rendered" (Evans-Freke v Showcase Contr. Corp., 85 AD3d at 962; see Johnson v Robertson, 131 AD3d at 672).

Although an unenforceable writing may provide evidence of the value of services rendered in quantum meruit (see Frank v Feiss, 266 AD2d at 826; Taylor & Jennings v Bellino Bros. Constr. Co., 106 AD2d 779, 780; see also Evans-Freke v Showcase Contr. Corp., 85 AD3d at 963), here, the record is devoid of evidence which would establish the reasonable value of the services Home Construction may have provided to the defendants (see Michaels v Byung Keun Song, 138 AD3d at 1075; see also Crown Constr. Bldrs. & Project Mgrs. Corp. v Chavez, 130 AD3d 969, 971-972; Geraldi v Melamid, 212 AD2d 575, 576). Neither the unsigned written proposal nor the testimony of Malo established the value of any services undertaken by Home Construction, or that the value of such services exceeded the amounts paid by the defendants. Accordingly, the Supreme Court properly dismissed Home Construction's cause of action to recover in quantum meruit for lack of proof (see Michaels v Byung Keun Song, 138 AD3d at 1075).

In contrast, the defendants, on their counterclaim, offered the testimony of experts regarding the cost they expended in completing or repairing roofing, flooring, brickwork, and other aspects of the project as set forth in the architectural plans. The Supreme Court properly concluded that the defendants were entitled to be compensated for the cost of completion of the construction work and the correction of defects in Home Construction's work, and the proper measure of damages is the fair and reasonable market price for correcting the defective installation or completing the construction (see Bellizzi v Huntley Estates, 3 NY2d 112, 115; Hodges v Cusanno, 94 AD3d 1168, 1169; Kaufman v Le Curt Constr. Corp., 196 AD2d 577, 578)."

Tuesday, September 26, 2017

Monday, September 25, 2017

Wednesday, September 20, 2017

Tuesday, September 19, 2017

SALARY HISTORY AND JOB APPLICATIONS IN NYC

Effective November 1, Section 8-107 of the administrative code of the city of New York is amended by adding a new subdivision 25 prohibiting employers from inquiring about or relying on a prospective employee's salary history. This amendment is designed to prohibit employers from inquiring about a prospective employee’s salary history during all stages of the employment process. In the event that an employer is already aware of a prospective employee’s salary history, this amendment would prohibit reliance on that information in the determination of salary. According to the sponsors of this legislation, when employers rely on salary histories to determine compensation, they perpetuate the gender wage gap. It is hoped that adopting measures like this amendment will reduce the likelihood that women will be prejudiced by prior salary levels and help break the cycle of gender pay inequity.

The new law can be found here http://legistar.council.nyc.gov/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=2813507&GUID=938399E5-6608-42F5-9C83-9D2665D9496F

Monday, September 18, 2017

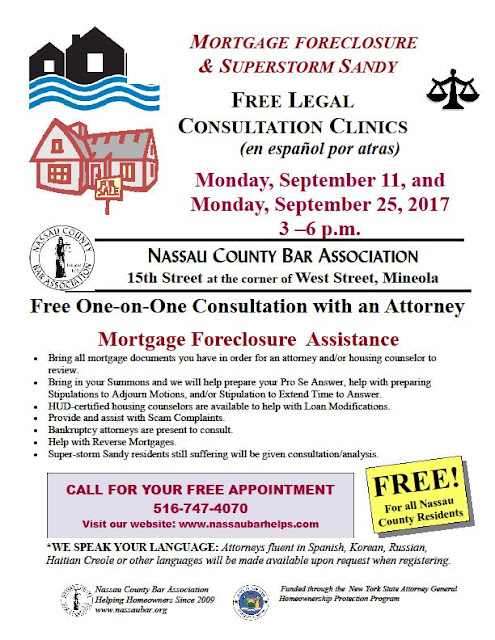

PRO BONO WORK IN LONG ISLAND

This morning, I will be a pro bono volunteer in landlord/tenant court in Nassau County. Nassau/Suffolk Law Services operates a nationally lauded pro bono program with the Bar Association of Nassau County and the Suffolk County Bar Association. Established in 1981, the program provides legal representation in civil cases for individuals meeting low income guidelines.

For more information, see http://nslawservices.org/wp/?page_id=392

Labels:

Nassau Suffolk Law Services,

Pro Bono

Friday, September 15, 2017

NEW RULES - ACCESS TO HEALTH RECORDS

On September 13, Governor Cuomo signed into law legislation amending the public health law and mental hygiene law to prohibit a charge from being imposed for providing, releasing, or delivering medical records that are used to support the application of a government benefit or program.

As per the Senate Bill:

"JUSTIFICATION : State law guarantees access to medical records for inspection or copying and provides a fee waiver for patients who cannot afford to pay. All too often, in practice, this does not occur. Complicated process for establishing eligibility and the outsourcing of copying services means that eligible low income New Yorkers are often required to pay for access to their own medical records in contravention of the law. Individuals applying for Social Security disability benefits (including Supplemental Security Income or SSI) need medical records to document their claims. These claimants cannot afford to pay the statutory rate of seventy five cents per page for these records, which often number in the 100s of pages. As a result, low income disabled individuals' ability to access federal disability benefits is consistently undermined. Current law does provide free access; however, the fee waiver is routinely ignored and is poorly enforced. Patients are denied free access for reasons such as medical providers do not tell patients that the fee may be waived, provider forms for requesting copies do not include fee waiver sections, complicated processes for determining patient indegence, and outsourcing of copying to companies that do not understand or enforce fee waiver protections."

S6078 - Details

- See Assembly Version of this Bill:

- A7842

- Law Section:

- Public Health Law

- Laws Affected:

- Amd §§17 & 18, Pub Health L; amd §33.16, Ment Hyg L

Labels:

Fees,

Medical Records,

Social Security

Thursday, September 14, 2017

UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE - A DOCILE EMPLOYEE?

Mailed and Filed: AUGUST 22, 2017, IN THE MATTER OF: Appeal Board No. 596410:

"The claimant worked for a hospital for over 18 years, ending in the position of unit receptionist in the Emergency Room. She worked overnight, from 11:00 PM to 7:00 AM. On March 18, 2016, the claimant was suspended for five days based on an incident in which, according to the "Employee Warning - Disciplinary Notice," the claimant yelled at a coworker over the phone and subsequently stormed into the coworker's area with a pen in her hand which the claimant kept moving in and out of the coworker's face as the claimant yelled at her, all of which was observable by at least one patient. The Employee Warning - Disciplinary Notice stated, "Any repeat will result in progressive discipline up to termination."

On January 8, 2017, the phone at the Emergency Room desk rang after the end of the

claimant's shift. The head nurse for the incoming shift asked the claimant why the claimant was not answering the phone. The claimant answered that she had given report already. In the hospital context, the claimant's answer meant that she had reported all updates to the incoming unit receptionist and she was now off duty. The head nurse then said, "then where are my URs?" A UR is a unit receptionist. Irritated by what she perceived as the head nurse's angry tone, the claimant responded, "I don't know and I don't care." Based on this final incident, the employer discharged the claimant for disruptive behavior after a prior warning. Her last day of work was January 31, 2017.

OPINION: The credible evidence establishes that the claimant was discharged based on the claimant's response of "I don't know and I don't care" after the claimant was spoken to-after the end of her shift-in a manner she perceived as rude. While the claimant's response may not have been entirely appropriate, a worker is not required always to be docile (see Matter of Raven, 40 AD2d 128 [3rd Dept 1972]). Further, the final incident is not comparable to the incident over which the claimant was warned. On January 8, 2017, the claimant did not "storm" anywhere, invade anyone's personal space, or raise her voice, nor is there any allegation that the claimant's single inappropriate comment was overheard by any patient. These facts establish that the claimant's statement does not rise to the level of misconduct for purposes of the Unemployment Insurance Law. The cases cited by the employer on appeal do not compel a different result. The claimant's comment was only minimally detrimental to the employer's interests, and the warning that the employer relies upon is distinguishable from the final incident."

Wednesday, September 13, 2017

FREE LEGAL CLINIC FOR VETERANS

Labels:

Free Clinic,

Veterans

Tuesday, September 12, 2017

SUPPORTING LEVITTOWN CHAMBER OF COMMERCE

Monday, September 11, 2017

Friday, September 8, 2017

NO "AID-IN-DYING" IN NEW YORK

Sara Myers et al. v. Eric Schneiderman et al., NYS Court of Appeals, Opinion 77, September 7, 2017:

"Plaintiffs ask us to declare a constitutional right to "aid-in-dying," which they define (and we refer to herein) as the right of a mentally competent and terminally ill person to obtain a prescription for a lethal dosage of drugs from a physician, to be taken at some point to cause death. Although New York has long recognized a competent adult's right to forgo life-saving medical care, we reject plaintiffs' argument that an individual has a fundamental constitutional right to aid-in-dying as they define it. We also reject plaintiffs' assertion that the State's prohibition on assisted suicide is not rationally related to legitimate state interests."

The full decision can be found here: http://www.nycourts.gov/ctapps/Decisions/2017/Sep17/77opn17-Decision.pdf

Labels:

assisted suicide,

Constitutional Rights,

New York

Thursday, September 7, 2017

NYSBA V. AVVO

The New York State Bar Association, Committee on Professional Ethics, issued Opinion 1132 on August 8, 2017 stating that a lawyer may not pay the current marketing fee to participate in Avvo Legal Services, because the fee includes an improper payment for a recommendation in violation of Rule 7.2(a) of the Rules of Professional Conduct.

The full opinion can be found here: http://www.nysba.org/EthicsOpinion1132/

Avvo's response of August 15 , 2017 can be found here:

http://lawyernomics.avvo.com/avvo-news/avvos-response-new-york-state-bar-associations-advisory-opinion.html

Labels:

Avvo,

Ethics,

New York State Bar Association

Wednesday, September 6, 2017

CAN AN INHERITANCE CHANGE A MAINTENANCE ORDER?

Schwartz v Schwartz 2017 NY Slip Op 06392 Decided on August 30, 2017 Appellate Division, Second Department:

"The parties divorced in 2008. Pursuant to the judgment of divorce, the defendant was required to pay to the plaintiff maintenance in the sum of $7,500 per month for the first 60 months, and $3,000 per month thereafter, until the death of either party or until the plaintiff remarried or held herself out as remarried. The defendant was further required to procure and maintain $750,000 of life insurance, naming the plaintiff as the sole and irrevocable beneficiary thereof.

In January 2015, the defendant moved to terminate his maintenance and life insurance obligations on the basis that the plaintiff's father had recently died, that the plaintiff was the only beneficiary of his estate, and that the late father's estate and assets were worth $15 to $20 million. The defendant contended that the plaintiff's large inheritance constituted a substantial change in circumstances which made her self-supporting. .....

........

"Upon application by either party, the court may annul or modify any prior order or judgment made after trial as to maintenance, . . . upon a showing of a substantial change in circumstances" (Domestic Relations Law § 236[B][9][b][1]). "The party seeking the modification of a maintenance award has the burden of establishing the existence of the change in circumstances that warrants the modification" (Noren v Babus, 144 AD3d 762, 764 [internal quotation marks omitted]; see Donnelly v Donnelly, 199 AD2d 237, 237). The inheritance of significant funds can constitute a substantial change of circumstances supporting a request to modify a party's maintenance obligation (see Matter of Greco v Greco, 251 AD2d 977, 978; see generally Dowdle v Dowdle, 114 AD2d 699, 700). "On a motion for downward modification of child support and maintenance obligations, an evidentiary hearing is necessary only where the proof submitted by the movant is sufficient to show the existence of a genuine issue of fact" (Reback v Reback, 93 AD3d 652, 652-653; see Ritchey v Ritchey, 82 AD3d 948, 949; David v David, 54 AD3d 714, 715; [*2]D'Alesio v D'Alesio, 300 AD2d 340, 341; Mishrick v Mishrick, 251 AD2d 558, 558; Senzer v Senzer, 132 AD2d 694, 694-695; Nordhauser v Nordhauser, 130 AD2d 561, 562-563).

........"

Labels:

divorce,

Modification,

Spousal Maintenance

Tuesday, September 5, 2017

ARE ATTORNEY FEES EXPENSES UNDER CPLR 3220

Saul v Cahan 2017 NY Slip Op 06391 Decided on August 30, 2017 Appellate Division, Second Department:

"...The plaintiff asserted causes of action alleging breach of fiduciary duty, breach of contract, and fraud, among others. In May 2014, Cahan moved, inter alia, pursuant to CPLR 3211(a)(7) to dismiss the amended complaint insofar as asserted against him. Shortly thereafter, on June 20, 2014, Cahan served an offer to liquidate damages pursuant to CPLR 3220. The plaintiff did not accept the offer. By order dated November 7, 2014, the Supreme Court granted Cahan's motion to dismiss the amended complaint insofar as asserted against him. Cahan then moved for an award of attorney's fees and costs pursuant to CPLR 3220. By order dated March 9, 2016, the court granted Cahan's motion to the extent of determining that [*2]Cahan was entitled to attorney's fees in the sum of $15,557.37, plus interest. A money judgment dated March 28, 2016, was entered in favor of Cahan and against Saul in the total sum of $16,697.14. The plaintiff appeals, and we reverse.

In matters of statutory interpretation, the primary consideration is to discern and give effect to the Legislature's intention (see Yatauro v Mangano, 17 NY3d 420, 426; Roberts v Tishman Speyer Props., L.P., 13 NY3d 270, 285-286; Matter of DaimlerChrysler Corp. v Spitzer, 7 NY3d 653, 660). "[T]he text of a provision is the clearest indicator of legislative intent and courts should construe unambiguous language to give effect to its plain meaning'" (Matter of Albany Law School v New York State Off. of Mental Retardation & Dev. Disabilities, 19 NY3d 106, 120, quoting Matter of DaimlerChrysler Corp. v Spitzer, 7 NY3d at 660; see Majewski v Broadalbin-Perth Cent. School Dist., 91 NY2d 577, 583). An examination of the legislative history is proper "where the language is ambiguous or where a literal construction would lead to absurd or unreasonable consequences that are contrary to the purpose of the enactment" (Matter of Auerbach v Board of Educ. of City School Dist. of City of N.Y., 86 NY2d 198, 204; see New York State Psychiatric Assn., Inc. v New York State Dept. of Health, 19 NY3d 17, 25-26).

Moreover, "under the American Rule as applied to statutory entitlement to attorneys' fees, the [United States] Supreme Court has held that we follow a general practice of not awarding fees to a prevailing party absent explicit statutory authority" (Baker v Health Mgmt. Sys., 98 NY2d 80, 88 [internal quotation marks omitted]; see 214 Wall St. Assoc., LLC v Medical Arts-Huntington Realty, 99 AD3d 988, 990). " New York public policy disfavors any award of attorneys' fees to the prevailing party in a litigation'" (Pickett v 992 Gates Ave. Corp., 114 AD3d 740, 740, quoting Horwitz v 1025 Fifth Ave., Inc., 34 AD3d 248, 249). " Statutes authorizing an award of costs and sanctions are in derogation of common law and, therefore must be strictly construed'" (State Farm Fire & Cas. v Parking Sys. Valet Serv., 85 AD3d 761, 764, quoting Saastomoinen v Pagano, 278 AD2d 218, 218).

CPLR 3220 states:

The relevant phrase of CPLR 3220 stating that the claimant "shall pay the expenses necessarily incurred by the party against whom the claim is asserted, for trying the issue of damages from the time of the offer" demonstrates the Legislature's intent that, where the claimant has not accepted the offer, the commencement of a trial is a condition precedent to imposing liability upon the claimant for the opposing party's expenses. This phrase also defines the recoverable expenses as those "necessarily" expended "for trying the issue of damages." CPLR 3220 further provides that those expenses should be determined by the judge "before whom the case is tried." Accordingly, the plain language of CPLR 3220 does not explicitly authorize an award of attorney's fees and costs to a party, such as Cahan, who merely prevailed in seeking dismissal of a cause of action alleging breach of contract. Even if CPLR 3220 could arguably support an implied right to the attorney's fees and costs sought by Cahan, the public policy of the American Rule militates against adoption of that interpretation (see Baker v Health Mgt. Sys., 98 NY2d at 88; 214 Wall St. Assoc., LLC v Medical Arts-Huntington Realty, 99 AD3d at 990)."

Labels:

Attorneys Fees,

CPLR 3220,

Settlement Offer

Friday, September 1, 2017

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)