TRUSTEES OF COLUMBIA UNIV. IN CITY OF NY v. D'AGOSTINO SUPERMARKETS, INC., 2020 NY Slip Op 6937 - NY: Court of Appeals November 24, 2020:

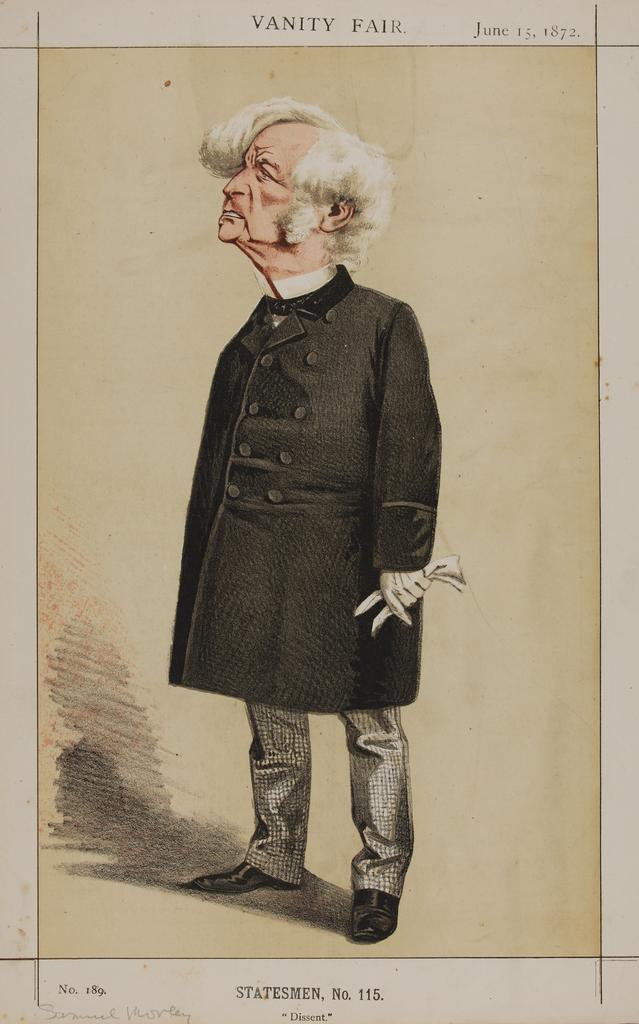

"DiFIORE, Chief Judge (dissenting).

After D'Agostino Supermarkets, Inc., the lessee of property owned by Columbia University, breached the lease by failing to pay rent for more than seven months, the parties settled their dispute by entering into a Surrender Agreement which contained certain conditions. If D'Agostino made timely installment payments totaling about $262,000, representing the rent it already owed but had failed to pay, it would be relieved of certain other obligations stemming from its breach of the lease. However, if it failed to timely make the payments, D'Agostino would not "be released and relieved from" the claims Columbia possessed as a result of the breach of the lease, particularly the right (as described in the Surrender Agreement) to collect "the aggregate amount of all Fixed Rent, additional rent or other sums and charges due" during the remainder of the lease term (about two years). It is undisputed that, after entering the Surrender Agreement, D'Agostino again failed to uphold its end of the bargain, breaching the condition to timely make the back-rent installment payments. Yet the majority concludes, as a matter of law, that D'Agostino—a well-counseled, sophisticated party who freely negotiated the terms of the settlement—should be relieved of its obligation to accept the consequences of that second breach. This result is incompatible with our freedom of contract precedent and the strong public policy favoring enforcement of settlement agreements. Worse yet, I fear it will chill future efforts to resolve lease disputes without litigation—to the detriment of distressed tenants. Therefore, I respectfully dissent.

As this Court recently reaffirmed in 159 MP Corp. v Redbridge Bedford, LLC, "`[f]reedom of contract prevails in an arm's length transaction between sophisticated parties . . ., and in the absence of countervailing public policy concerns there is no reason to relieve them of the consequences of their bargain'" (33 NY3d 353, 359 [2019], quoting Oppenheimer & Co. v Oppenheim, Appel, Dixon & Co., 86 NY2d 685, 695 [1995]). The public policy underlying freedom of contract is twofold: "[b]y disfavoring judicial upending of the balance struck at the conclusion of the parties' negotiations" it "both promotes certainty and predictability and respects the autonomy of commercial parties in ordering their own business arrangements" (159 MP Corp., 33 NY3d at 359-360). Accordingly, "`when parties set down their agreement in a clear, complete document, their writing should . . . be enforced according to its terms'" (159 MP Corp., 33 NY3d at 358, quoting Vermont Teddy Bear Co. v 538 Madison Realty Co., 1 NY3d 470, 475 [2004]). This principle of New York contract law has "special import" in real property transactions where, as here, "commercial certainty is a paramount concern" (159 MP Corp., 33 NY3d at 359, quoting Vermont Teddy Bear, 1 NY3d at 475).

The public policy favoring freedom of contract applies with particular force to the Surrender Agreement—which is a settlement agreement crafted by the parties to resolve their dispute without litigation. Settlement agreements "are judicially favored and may not be lightly set aside" (IDT Corp. v Tyco Group, S.A.R.L., 13 NY3d 209, 213 [2009] [citation omitted]). Strict enforcement of settlement agreements serves multiple important purposes, consistent with those underlying freedom of contract. There is a "societal benefit in recognizing the autonomy of parties to shape their own solution to a controversy" and assurance that their agreements will be honored provides them "finality and repose upon which [to] order their affairs" (Denburg v Parker Chapin Flattau & Klimpl, 82 NY2d 375, 383 [1993]). Moreover, settlement agreements are favored because they also promote "efficient dispute resolution" (IDT Corp., 13 NY3d at 213), "avoid[ing] potentially costly, time-consuming litigation and preserv[ing] scarce judicial resources" as "courts could not function if every dispute devolved into a lawsuit" (Denburg, 82 NY2d at 383; see also IDT Corp., 13 NY3d at 213). As Columbia has consistently argued throughout this litigation, these policies, and the significant interests they protect, should guide the resolution of this dispute between two sophisticated, counseled commercial entities.

The majority casts these principles aside, failing to acknowledge that the Surrender Agreement constituted a settlement of the claims Columbia possessed upon D'Agostino's breach of the lease, which included a right to collect—not only unpaid back rent—but also future rent owed until the conclusion of the lease term, even if D'Agostino vacated the premises (Columbia had no obligation under the lease to relet the property). Columbia agreed to settle under terms that significantly discounted the amount it would collect on account of D'Agostino's breach of the lease, but did so only on the condition that D'Agostino timely make eleven installment payments representing the back rent D'Agostino already owed at the time the parties entered the Surrender Agreement. Because that rent was several months overdue, it is no surprise that Columbia required the inclusion of a clause that "TIME SHALL BE OF THE ESSENCE with respect to the [due] dates" for those installment payments. The parties' agreement could not be clearer that Columbia waived certain claims it possessed arising from D'Agostino's breach of the lease only if this condition—timely payment of the installments—was met. Under the plain language of the agreement, upon D'Agostino's default or failure to timely cure upon notice, two things would occur: D'Agostino would immediately be obligated to pay the future rent due under the lease (among other associated payments) and it would "no longer be entitled to be released and relieved from and against any Released Claims." Of course, it is undisputed that D'Agostino breached yet again.

Notwithstanding the context of the Surrender Agreement and its plain language, the majority mistakenly concludes that the Surrender Agreement should be interpreted without reference to the prior breach of the lease and that D'Agostino was relieved of all obligations under the lease even if it failed to timely make the installment payments. Although the Surrender Agreement "terminated the lease," it most certainly did not unconditionally release the tenant of all obligations flowing from its breach of that prior agreement, and the majority's assertion that Columbia seeks to "enforce a non-existent lease under the guise of damages for a breach of a separate contract" (majority op at 8) misses the mark. Columbia does not attempt to enforce the lease—instead, it seeks to enforce the contingent remedy the parties adopted in the Surrender Agreement in the event D'Agostino failed to timely make the Surrender Payments.

The practical result of the majority's holding is that Columbia University received nothing in exchange for its agreement (1) to give the tenant additional time to make back rent payments that were already overdue, provided those payments were timely made, and (2) to forfeit its right to collect future rent from D'Agostino for its breach of the lease. Under the majority's analysis, the carefully negotiated consequence of D'Agostino's continued failure to pay the back rent is unenforceable; indeed, there is no consequence for D'Agostino's breach of the Surrender Agreement and D'Agostino is rewarded for serial breaches of valid and binding contracts. The majority accomplishes this result through a strained application of this Court's precedent related to liquidated damages clauses, reasoning that the provision reinstating D'Agostino's obligation to pay future rent in the event of a second breach operates as an unenforceable penalty because the damages D'Agostino would be obligated to pay upon breach of the Surrender Agreement were substantially greater than the discounted damages Columbia agreed to accept in the form of promptly tendered installment payments. This remedy provision in the contract is best understood as a component of a settlement after a breach—not a liquidated damages clause crafted at the beginning of a contractual relationship. Nonetheless, even viewing the contingent language as a liquidated damages clause, when properly interpreted in the context of the entire agreement, it is not an unenforceable penalty justifying a deviation from application of our bedrock freedom of contract principles.

As we have recognized, the public policy favoring freedom of contract can be "overridden by another weighty and countervailing public policy" (159 MP Corp., 33 NY3d at 360). The majority concludes that such a countervailing public policy is at play here, viewing the contingent remedy as an unenforceable liquidated damages clause. But "[a]s a general matter parties are free to agree to a liquidated damages clause `provided that the clause is neither unconscionable nor contrary to public policy'" (172 Van Duzer Realty Corp. v Globe Alumni Student Assistance Assn., Inc., 24 NY3d 528, 536 [2014], quoting Truck Rent-A-Ctr. v Puritan Farms 2nd, 41 NY2d 420, 424 [1977]). Liquidated damages provisions serve an important purpose because they allow parties to estimate—in advance of a default—the extent of the injury resulting from the breach of the agreement and are, therefore, particularly useful "where it would be difficult, if not actually impossible, to calculate the amount of actual damage" (Truck Rent-A-Ctr., 41 NY2d at 424). Nevertheless, "public policy is firmly set against the imposition of penalties or forfeitures for which there is no statutory authority" (id.)—and thus, a liquidated damages clause that operates as a penalty will not be enforced. A liquidated damages clause operates as an impermissible penalty only when it provides for damages "plainly or grossly disproportionate to the probable loss," as such a penalty "is not intended to provide fair compensation" (id. at 425). By comparison, it is enforceable when "the amount liquidated bears a reasonable proportion to the probable loss" (id.).

In this case, although the parties referred to the contingent remedy as a "liquidated damages clause," the label is ill-fitting. The public policy underlying our liquidated damages jurisprudence is simply not implicated in circumstances where, as in this case, there is no need to estimate the damages that might result in the event of a future breach because the breach has already occurred and the parties are crafting a settlement agreement. But even viewing the contingent remedy as a liquidated damages clause, the majority's conclusion that the provision reinstating D'Agostino's obligation to pay future rent is an unenforceable penalty because it provides for damages "exponentially disproportionate" to D'Agostino's outstanding Surrender Payments (approximately $1 million versus $176,000) adopts an overly simplistic view of the Surrender Agreement and fails to "giv[e] due consideration to the nature of the contract and the circumstances" in which it was entered, as our precedent requires (172 Van Duzer Realty Corp., 24 NY3d at 536)[6] . It is evident from the Surrender Agreement that the parties understood that D'Agostino's liability for breach of the lease was much greater than the value of the Surrender Payments. The obligations triggered if those payments were not timely made were not included merely as compensation for breach of the Surrender Agreement but were also intended to compensate Columbia for D'Agostino's earlier breach of the lease. Thus, an analysis of whether the damages set forth in the Surrender Agreement are grossly disproportionate to Columbia's probable losses requires consideration not only of the value of the Surrender Payments that D'Agostino failed to make, but also of the probable damages already set in motion by D'Agostino's prior breach of the lease, viewed from the time the Surrender Agreement was executed and not the date of the breach (see Truck Rent-A-Ctr., 41 NY2d at 425).

When the agreement was executed, Columbia possessed a right to pursue the full value of future rent payments until the conclusion of the lease term. At that time, there was no assurance that Columbia would sign a new tenant (and what costs might be incurred in that process), nor did the parties know the amount of rent Columbia might be able to negotiate or whether a new tenant would timely pay during the remainder of the original lease term. Thus, the remedy negotiated by the parties in the Surrender Agreement was directly premised on Columbia's rights under the lease, bears a "reasonable relation" to Columbia's probable actual harm, and was intended to fairly compensate Columbia for that breach (see generally Truck Rent-A-Ctr., 41 NY2d 420). Measured in a way that adequately recognizes the nature of the bargain struck in the Surrender Agreement, D'Agostino has not met its burden to show that the damages set forth in that agreement are so disproportionate as to operate as an unenforceable penalty (see generally JMD Holding Corp. v Congress Fin. Corp., 4 NY3d 373, 380, 385 [2005]).

It is irrelevant that Columbia's actual damages here may ultimately be different than the amount D'Agostino agreed to pay in the contingent remedy provision of the Surrender Agreement. The enforceability of a liquidated damages clause does not turn on whether the remedy that the parties contemplated before the breach occurred is identical to the damages actually suffered. To impose such a requirement would obviate the entire purpose of such provisions, which is to reasonably estimate the damages that might result, permitting the parties to avoid the costs and uncertainty of litigating damages in the event of a future breach. For this reason, the rough relationship between the remedy in the contract and the damages flowing from a breach must be assessed based on the terms of the agreement and the information the parties possessed at the time it was executed—not with the benefit of hindsight based on post hoc proof of damages actually incurred.

Refusing to enforce the contingent remedy that the parties contracted for in their settlement agreement injects uncertainty into commercial tenancy agreements and the settlement of disputes thereunder, increasing the parties' transaction costs. It also rewards a sophisticated, represented party for breaching its validly-entered agreements. This will discourage commercial landlords from agreeing to settlements of this nature, to the detriment of defaulting tenants like D'Agostino; limiting the damages recoverable when such settlements are breached to the discounted amount provided for in the restructured contract, even in the event of a new breach, removes any incentive for landlords to agree to settle by permitting tenants who have already defaulted to default again without recourse.

Because there was nothing unfair about the settlement crafted by these well-counseled sophisticated parties, public policy affords no basis to alter their contract. Since the back rent payments were already substantially overdue, Columbia reasonably sought assurance that D'Agostino would uphold its end of the bargain under the Surrender Agreement (something it failed to do under the lease). As reflected in the plain language of the agreement, Columbia was willing to forego pursuit of its then-existing right to collect both unpaid back rent and future rent only if D'Agostino timely made the back rent installment payments (the owner gave up its right to receive more money overall but would be assured of prompt payment of a discounted amount on a regular schedule, without the need for litigation). Of course, that is not what happened. By eliminating the element that induced the owner to give up its rights, the majority creates a distorted, one-sided settlement in which—despite its default—D'Agostino was able to enjoy the full benefit of the bargain. Because freedom of contract should "prevail[] in [this] arm's length transaction between sophisticated parties" (159 MP Corp., 33 NY3d at 359) and there is no countervailing public policy basis that would justify relieving D'Agostino of the bargain it struck in the Surrender Agreement, I respectfully dissent.

Order affirmed, with costs.

......

[6] The majority reasons that the circumstances here are like that in 172 Van Duzer—but it then fails to grant the relief provided in that case, which did not declare the provision unenforceable but, rather, remitted for a hearing to explore whether the damages were "grossly disproportionate." In fact, 172 Van Duzer does not stand for the proposition that a provision is unenforceable merely because it required immediate payment of all future rent due under a lease. There, the acceleration clause was negotiated in advance of any breach, the default occurred early in the course of a long-term lease and, as the Court observed, strict enforcement of the provision would have resulted in a lump sum payment of eight years of future rent, not discounted to present value (24 NY3d at 536). Even then we did not void the clause but directed further litigation of the issue—a remedy Columbia seeks in the alternative here. The majority inexplicably fails to explain why the hearing deemed necessary in 172 Van Duzer is not afforded here, where the purported liquidated damages clause was negotiated after the tenant's initial breach with only about two years remaining on the lease.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.