TITUMIR v. BARKER AVE. ESTATES LLC, 2022 NY Slip Op 50073 - Bronx Supreme Court 2022:

"In this action for, inter alia, breach of a non-delegable

duty, defendants move seeking an order granting them summary judgment.

Saliently, defendants aver that the lease between the parties precludes

liability for the alleged water leak in the complaint, such that summary

judgment is warranted. Plaintiff opposes the instant motion,

procedurally asserting that discovery is not yet complete such that the

instant motion is premature. Substantively, plaintiff contends that the

portion of the lease upon which defendants rely does not bar liability

against defendants, because to the extent it bars liability for

defendants' negligence, General Obligations Law § 5-321 renders the

relevant portion of the lease unenforceable.

For the reasons that follow hereinafter, defendants' motion is granted.

The instant action is for money damages arising from the failure to

maintain a premises. The complaint alleges that the plaintiff and

defendants' predecessor in both ownership and interest entered into a

commercial lease for the premises located at Store No.7DE, 671 Allerton

Avenue, Bronx NY 10467 (Store #7DE), whose term was from December 1,

2007 to November 30, 2022. Plaintiff was a merchant of discount

hardware, discount housewares, a paint supplier and a seller of

household goods, who would operate a store at Store #7DE. On July 24,

2017, water began to leak from apartments above Store #7DE, causing the

store's ceiling to collapse and causing water to enter the store. The

water flooded the store causing damage to plaintiff's goods,

merchandise, the floor, the electrical wiring, the pipes and the light

fixtures. As a result, plaintiff was forced to close the store, causing a

loss of business. Plaintiff notified defendants, who after a protracted

period of time attempted to fix the leak. Despite the repair, water

nonetheless continued to leak into the store. Based on the foregoing

plaintiff alleges that defendants failed to comply with their

non-delegable duty to maintain and make repairs within Store #7DE (First

Cause of Action). Plaintiff also alleges that based on the foregoing,

despite having to close the store, he nevertheless continued to pay rent

such that defendants breached the implied warranty of quiet enjoyment

(Second Cause of Action). Lastly, plaintiff alleges that despite

notifying defendants of the water condition within Store #7DE,

defendants nonetheless failed to repair the same and then when they made

repairs, they failed to ameliorate the condition. As such, plaintiff

alleges that defendants were negligent (Third Cause of Action).

Standard of Review

The proponent of a motion for summary judgment carries the initial

burden of tendering sufficient admissible evidence to demonstrate the

absence of a material issue of fact as a matter of law (Alvarez v Prospect Hospital, 68 NY2d 320, 324 [1986]; Zuckerman v City of New York, 49 NY2d 557, 562 [1980]).

Thus, a defendant seeking summary judgment must establish prima facie

entitlement to such relief by affirmatively demonstrating, with

evidence, the merits of the claim or defense, and not merely by pointing

to gaps in plaintiff's proof (Mondello v DiStefano, 16 AD3d 637, 638 [2d Dept 2005]; Peskin v New York City Transit Authority, 304 AD2d 634, 634

[2d Dept 2003]). There is no requirement that the proof be submitted by

affidavit, but rather that all evidence proffered be in admissible form

(Muniz v Bacchus, 282 AD2d 387, 388 [1st Dept 2001], revd on other grounds Ortiz v City of New York, 67 AD3d 21, 25

[1st Dept 2009]). Notably, the court can consider otherwise

inadmissible evidence, when the opponent fails to object to its

admissibility and instead relies on the same (Niagara Frontier Tr. Metro Sys. v County of Erie, 212 AD2d 1027, 1028 [4th Dept 1995]).

Once movant meets his initial burden on summary judgment, the burden

shifts to the opponent who must then produce sufficient evidence,

generally also in admissible form, to establish the existence of a

triable issue of fact (Zuckerman at 562). It is worth noting,

however, that while the movant's burden to proffer evidence in

admissible form is absolute, the opponent's burden is not. As noted by

the Court of Appeals, [t]o obtain summary judgment it is necessary that

the movant establish his cause of action or defense `sufficiently to

warrant the court as a matter of law in directing summary judgment' in

his favor, and he must do so by the tender of evidentiary proof in

admissible form. On the other hand, to defeat a motion for summary

judgment the opposing party must `show facts sufficient to require a

trial of any issue of fact.' Normally if the opponent is to succeed in

defeating a summary judgment motion, he too, must make his showing by

producing evidentiary proof in admissible form. The rule with respect to

defeating a motion for summary judgment, however, is more flexible, for

the opposing party, as contrasted with the movant, may be permitted to

demonstrate acceptable excuse for his failure to meet strict requirement

of tender in admissible form. Whether the excuse offered will be

acceptable must depend on the circumstances in the particular case (Friends of Animals v Associated Fur Manufacturers, Inc., 46 NY2d 1065, 1067-1068 [1979]

[internal citations omitted]). Accordingly, generally, if the opponent

of a motion for summary judgment seeks to have the court consider

inadmissible evidence, he must proffer an excuse for failing to submit

evidence in admissible form (Johnson v Phillips, 261 AD2d 269, 270 [1st Dept 1999]).

When deciding a summary judgment motion the role of the Court is to

make determinations as to the existence of bonafide issues of fact and

not to delve into or resolve issues of credibility. As the Court stated

in Knepka v Talman (278 AD2d 811, 811 [4th Dept 2000]),

[s]upreme Court erred in resolving issues of credibility in granting

defendants' motion for summary judgment dismissing the complaint. Any

inconsistencies between the deposition testimony of plaintiffs and their

affidavits submitted in opposition to the motion present issues for

trial(see also Yaziciyan v Blancato, 267 AD2d 152, 152 [1st Dept 1999]; Perez v Bronx Park Associates, 285 AD2d 402, 404

[1st Dept 2001]). Accordingly, the Court's function when determining a

motion for summary judgment is issue finding, not issue determination (Sillman v Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., 3 NY2d 395, 404 [1957]).

Lastly, because summary judgment is such a drastic remedy, it should

never be granted when there is any doubt as to the existence of a

triable issue of fact (Rotuba Extruders v Ceppos, 46 NY2d 223, 231 [1978]). When the existence of an issue of fact is even debatable, summary judgment should be denied (Stone v Goodson, 8 NY2d 8, 12 [1960]).

Contract Law and Leases

It has long been held that absent a violation of law or some

transgression of public policy, people are free to enter into contracts,

making whatever agreement they wish, no matter how unwise they may seem

to others (Rowe v Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, Inc., 46 NY2d 62, 67-68 [1978]). Consequently, when a contract dispute arises, it is the court's role to enforce the agreement rather than reform it (Grace v Nappa, 46 NY2d 560, 565 [1979]).

In order to enforce the agreement, the court must construe it in

accordance with the intent of the parties, the best evidence of which

being the very contract itself and the terms contained therein (Greenfield v Philles Records, Inc., 98 NY2d 562, 569 [2002]).

It is well settled that "when the parties set down their agreement in a

clear, complete document, their writing should be enforced according to

its terms" (Vermont Teddy Bear Co., Inc. v 583 Madison Realty Company, 1 NY3d 470, 475 [2004]

[internal quotation marks omitted]). Moreover, "a written agreement

that is complete, clear and unambiguous on its face must be enforced

according to the plain meaning of its terms" (Greenfield at 569).

Accordingly, courts should refrain from interpreting agreements in a

manner which implies something not specifically included by the parties,

and courts may not by construction add or excise terms, nor distort the

meaning of those used and thereby make a new contract for the parties

under the guise of interpreting the writing (Vermont Teddy Bear Co., Inc.

at 475). This approach serves to preserve "stability to commercial

transactions by safeguarding against fraudulent claims, perjury, death

of witnesses [and] infirmity of memory" (Wallace v 600 Partners Co., 86 NY2d 543, 548 [1995] [internal quotation marks omitted]).

The proscription against judicial rewriting of contracts is

particularly important in real property transactions, where commercial

certainty is paramount, and where the agreement was negotiated at arm's

length between sophisticated, counseled business people (Vermont Teddy Bear Co., Inc.

at 475). Specifically, in real estate transactions, parties to the sale

of real property, like signatories of any agreement, are free to tailor

their contract to meet their particular needs and to include or exclude

those provisions which they choose. Absent some indicia of fraud or

other circumstances warranting equitable intervention, it is the duty of

a court to enforce rather than reform the bargain struck (Grace v Nappa, 46 NY2d 560, 565 [1979]).

Leases are nothing more than contracts and are thus subject to the

rules of contract interpretation, namely, that the intent of the parties

is to be given paramount consideration, which intent is to be gleaned

from the four corners of the agreement, and that of course, the court

may not rewrite the contract for the parties under the guise of

construction, nor may it construe the language in such a way as would

distort the contract's apparent meaning (Tantleff v Truscelli, 110 AD2d 240, 244 [2d Dept 1985]).

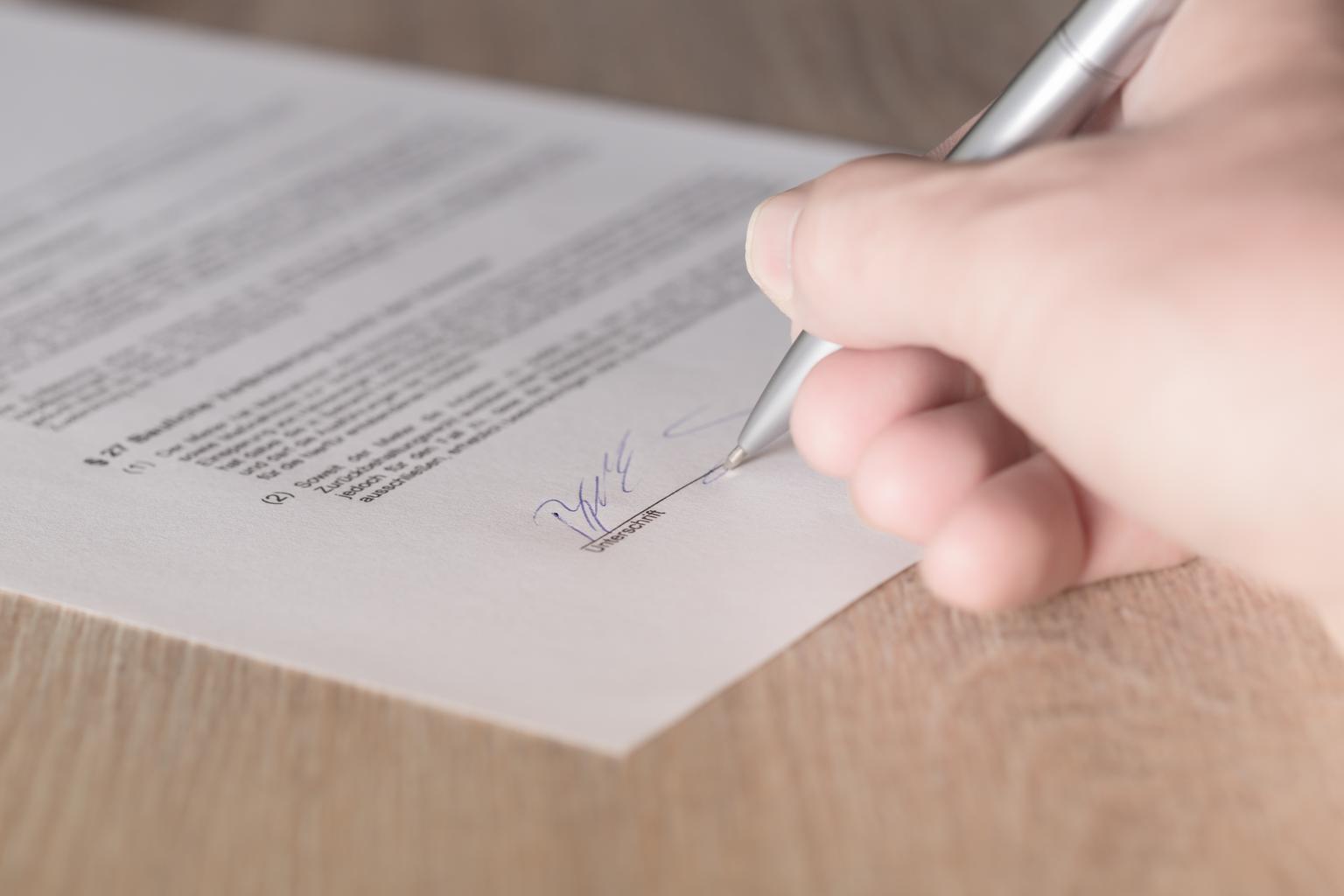

In the absence of fraud or other wrongful act, a party who signs a

written contract is presumed to know and have assented to the contents

therein (Pimpinello v Swift & Co., 253 NY 159, 162 [1930]; Metzger v Aetna Ins. Co., 227 NY 411, 416 [1920]; Renee Knitwear Corp. v ADT Sec. Sys., 277 AD2d 215, 216 [2d Dept 2000]; Barclays Bank of New York, N.A. v Sokol, 128 AD2d 492, 493 [2d Dept 1987]; Slater v Fid. & Cas. Co. of NY, 277 AD 79, 81 [1st Dept 1950]). In discussing this long-standing rule the court in Metzger

stated that [i]t has often been held that when a party to a written

contract accepts it as a contract he is bound by the stipulations and

conditions expressed in it whether he reads them or not. Ignorance

through negligence or inexcusable trustfulness will not relieve a party

from his contract obligations. He who signs or accepts a written

contract, in the absence of fraud or other wrongful act on the part of

another contracting party, is conclusively presumed to know its contents

and to assent to them and there can be no evidence for the jury as to

his understanding of its terms. This rule is as applicable to insurance

contracts as to contracts of any kind. (Metzger at 416 [internal citations omitted]).

Generally, pursuant to GOL § 5-321, a provision in a lease seeking to

exempt a party for his own negligence is void and unenforceable as

against public policy (Great N. Ins. Co. v Interior Const. Corp., 18 AD3d 371, 372 [1st Dept 2005], affd, 7 NY3d 412 [2006]; Tormey v City of New York, 302 AD2d 277, 278 [1st Dept 2003]; Gibson v Bally Total Fitness Corporation, 1 AD3d 477, 479 [2d Dept 2003]; Radius, Ltd. v Newhouse, 213 AD2d 614, 615 [2d Dept 1995]). To be sure, GOL § 5-321 states that

[e]very covenant, agreement or understanding in or in

connection with or collateral to any lease of real property exempting

the lessor from liability for damages for injuries to person or property

caused by or resulting from the negligence of the lessor, his agents,

servants or employees, in the operation or maintenance of the demised

premises or the real property containing the demised premises shall be

deemed to be void as against public policy and wholly unenforceable.

However, case law has carved an exception to the prohibition

described in the GOL §5-321. Specifically, it is well settled that an

indemnification agreement in a lease shall be enforceable even if the

lessor seeks to have the lessee indemnify him for his own negligence

when the lease is the product of "sophisticated parties negotiating at

arm's length," and "have agreed to allocate the risk of liability to

third parties between themselves, essentially through the employment of

insurance" (Great N. Ins. Co. at 372; see Hogeland v Sibley, Lindsay & Curr Co., 42 NY2d 153, 161 [1977]. In explaining why GOL §5-321 does not apply in the foregoing circumstances, the court in Hogeland

stated that [t]he legislative history and the statute's express

invalidation of any agreement `exempting the lessor from liability for

damages for injuries resulting from the negligence of the lessor'

strongly suggests that is was directed primarily to exculpatory clauses

in leases whereby lessors are excused from direct liability for

otherwise valid claims which might be brought against them by others. It

and several parallel provisions prohibit agreements which free

landlords (or others in comparable relationships) from all

responsibility to a tenant (or others) for negligence; the former are

thus compelled at their own peril to retain the incentive to act

prudently. It is against this background of declared purpose that the

indemnification clauses before us must be considered. So analyzed,

Berenson is not exempting itself from liability to the victim for its

own negligence. Rather, the parties are allocating the risk of liability

to third parties between themselves, essentially through the employment

of insurance. Courts do not, as a general matter, look unfavorably on

agreements which, by requiring parties to carry insurance, afford

protection to the public (internal citations omitted)(Hogeland at 160-161). Thus, in both Hogeland and Great N. Ins. Co., the lessees were obligated to indemnify the lessors, even though they had been found negligent Hogeland at 158; Great N. Ins. Co. at 372).

Discussion

Defendants' motion seeking summary judgment is granted.

Significantly, on this record, defendants establish that the lease and

rider which bind the parties contains a provision which exempt

defendants from any liability arising from the water leak alleged in the

complaint. The record also establishes that insofar as this is a

commercial tenancy, the lease falls within the ambit of the exception to

the rule prescribed by GOL § 5-321, which renders unenforceable a lease

provision such as the one in the lease and rider between the parties,

which exempts defendants from all liability, which necessarily includes

their negligent acts.

In support of the instant motion, defendants submit an affidavit by

Arie Weissman (Weissman), defendants' Managing Agent, who states that

the lease and rider appended to defendants' motion are true and

accurate.

Defendants provide the lease and rider between the parties[1]. The lease is dated November 29, 2007, is between plaintiff and Solomon Management Co., LLC., and is for Store #7DE[2].

Paragraph two of the lease makes plaintiff responsible for the

maintenance of the "premises, fixtures, and appurtenances," requiring

that plaintiff "make all repairs in and about the same necessary to

preserve them in good order and condition." Paragraph thirteen of the

lease states that

[t]he Landlord shall not be liable for any failure of water supply or

electrical current, sprinkler damage, or failure of a sprinkler

service, nor for injury or damage to a person or property caused by the

elements or by other tenants or persons in said building, or resulting

from steam, gas, electricity, water, rain or snow, which may leak or

flow form any part of said building, or from pipes, appliances or

plumbing works of the same, or from the street or sub-surface, or from

any other place nor for interference with light or other incorporeal

hereditaments by anybody other than the Landlord, or caused by

operations by or for a government authority in construction of any

public or quasi-public work, neither shall the Landlord be liable for

any latent defect in the building.

The rider is also dated November 29, 2007. Paragraph 13 of the rider

reiterates paragraph two of the lease and paragraph 10 of the rider

reiterates paragraph thirteen of the lease. Significantly, paragraph 2

of the rider states that

[t]he Tenant shall, at-his own cost and expense, during the

whole term of this Lease and of any renewal agreements, have ready

before the commencement of this Lease his own fire and liability

insurance including the Broad Form Comprehensive Liability endorsement

covering the demised premises; general public liability insurance with

limits of not less than $750,000 with respect to death or personal

injury to any one person and any one occurrence; for bodily injury and

property damage, in the amounts not less than $350,000; and shall

maintain the same in full force and effect throughout the entire term of

this Lease and of any renewal thereof.

Based on the foregoing, defendants establish prima facie entitlement to summary judgment.

Preliminarily, contrary to plaintiff's assertion, he fails to

establish that the instant motion is procedurally premature pursuant to

CPLR § 3212(f) on grounds that discovery has not yet been completed.

Pursuant to CPLR § 3212(f), a motion for summary judgment will be

denied if it appears that facts necessary to oppose the motion exist but

are unavailable to the opposing party. Denial is particularly warranted

when the facts necessary to oppose the motion are within the exclusive

knowledge of the moving party (Franklin National Bank of Long Island v De Giacomo, 20 AD2d 797, 797 [2d Dept 1964]; De France v Oestrike, 8 AD2d 735, 735-736 [2d Dept 1959]; Blue Bird Coach Lines, Inc. v 107 Delaware Avenue, N.V., Inc., 125 AD2d 971, 971

[4th Dept 1986]). However, when the information necessary to oppose the

motion is wholly within the control of the party opposing summary

judgment and could be produced via sworn affidavits, denial of a motion

for summary judgment pursuant to CPLR § 3212(f) will be denied (Johnson v Phillips, 261 AD2d 269, 270 [1st Dept 1999]).

A party claiming ignorance of the facts critical to defeat a motion

for summary judgment is only entitled to further discovery and denial of

a motion for summary judgment if he or she demonstrates that reasonable

attempts were made to discover facts which, as the opposing party

claims, would give rise to a triable issue of fact (Sasson v Setina Manufacturing Company, Inc., 26 AD3d 487, 488 [2d Dept 2006]; Cruz v Otis Elevator Company, 238 AD2d 540, 540

[2d Dept 1997]). Implicit in this rationale is that the proponent of

further discovery must identify facts, which would give rise to triable

issues of fact. This is because a court cannot condone fishing

expeditions and as such, "[m]ere hope and speculation that additional

discovery might uncover evidence sufficient to raise a triable issue of

fact is not sufficient" (Sasson at 501). Thus, additional

discovery should not be ordered where the proponent of the additional

discovery has failed to demonstrate that the discovery sought would

produce relevant evidence (Frith v Affordable Homes of America, Inc., 253 AD2d 536, 537

[2d Dept 1998]).Notwithstanding the foregoing, CPLR § 3212(f) mandates

denial of a motion for summary judgment when a motion for summary

judgment is patently premature, meaning when it is made prior to the

preliminary conference, if no discovery has been exchanged (Gao v City of New York, 29 AD3d 449, 449 [1st Dept 2006]; Bradley v Ibex Construction, LLC, 22 AD3d 380, 380-381 [1st Dept 2005]; McGlynn v Palace Co., 262 AD2d 116, 117

[1st Dept 1999]). Under these circumstances, the proponent seeking

denial of a motion as premature need not demonstrate what discovery is

sought, that the same will lead to discovery of triable issues of fact

or the efforts to obtain the same have been undertaken (id.). In Bradley,

the court denied plaintiff's motion for summary judgment as premature,

when the same was made prior to the preliminary conference (Bradley at 380). In McGlynn,

the court denied plaintiff's motion seeking summary judgment, when the

same was made after the preliminary conference but before defendant had

obtained any discovery whatsoever (McGlynn at 117).

Here, the parties attended a preliminary conference on January 25,

2021, which resulted in an order prescribing discovery that very day.

Thus, the instant motion is not premature on grounds that no discovery

conferences have yet been held. Moreover, to the extent that plaintiff's

sole assertion on this issue is merely that "[d]iscovery has not been

completed," he fails to establish, as required, what attempts were made

to discover the facts he needs, which are critical to defeat this

motion, and which are in defendants' possession (Sasson at 488; Cruz at 540).

Substantively, defendants establish that the commercial lease between

the parties bars any liability as against defendants for the water leak

alleged in the complaint. As noted above, leases are nothing more than

contracts and are thus subject to the rules of contract interpretation,

namely, that the intent of the parties is to be given paramount

consideration, which intent is to be gleaned from the four corners of

the agreement, and that of course, the court may not rewrite the

contract for the parties under the guise of construction, nor may it

construe the language in such a way as would distort the contract's

apparent meaning (Tantleff at 244).

Here, paragraph two of the lease and 13 of the rider establish that

plaintiff agreed to completely maintain Store #7DE. More significantly,

paragraph 13 of the lease and 10 of the rider establishes that with

regard to water leaks emanating from pipes within Store #7DE, and

causing damage, as alleged in the complaint, defendants would bear no

liability whatsoever. Thus, per the clear and unambiguous language of

the lease and rider, the instant action is barred.

While it is true that pursuant to GOL § 5-321, a provision in a lease

seeking to exempt a party for his own negligence is void and

unenforceable as against public policy (Great N. Ins. Co. at 372; Tormey at 278; Gibson at 479; Radius, Ltd.

at 615), it is equally true that an indemnification agreement in a

lease shall be enforceable even if the lessor seeks to have the lessee

indemnify him for his own negligence when the lease is the product of

"sophisticated parties negotiating at arm's length," and "have agreed to

allocate the risk of liability to third parties between themselves,

essentially through the employment of insurance" (Great N. Ins. Co. at 372; see Hogeland at 161).

Here, while a fair reading of paragraph thirteen of the lease and 10

of the rider clearly insulates defendants from all liability from the

conditions alleged therein, such that liability is barred for their own

negligent conduct, paragraph 2 of the rider brings paragraph thirteen of

the lease and 10 of the rider within the ambit of the exception to GOL §

5-321. To be sure, insofar as paragraph 2 of the rider mandates that

plaintiff purchase insurance insuring it for property damage, it is

clear that the parties to this commercial lease sought to allocate

plaintiff's risk, the very same for which he sues, to a third-party,

namely the insurance company.

Accordingly, defendants establish that even if they were negligent in

the maintenance of the Store #7DE, the lease between the parties bars

this action (Great N. Ins. Co. at 372; see Hogeland at

161). By operation of law, this is necessarily true for the second cause

of action for breach of the implied warranty of quiet enjoyment, since

to hold otherwise, would render paragraph 13 of the lease and 10 of the

rider meaningless. Indeed, a violation of the implied warranty of quiet

enjoyment would impose the very liability upon defendants that they

sought, through negotiation, to avoid.

The Court also holds, as urged by defendants, that the first cause of

action, premised on an alleged non-delegable duty requiring defendants

to maintain Store #7DE, fails as a matter of law. As noted by the lease

and rider, the tenancy at issue is commercial and not residential. As

such, the non-delegable duty pleaded by plaintiff and the legal

authority for which he never identifies, does not exist. To be sure,

while Multiple Dwelling Law § 78(1) states that "[e]very multiple

dwelling, including its roof or roofs, and every part thereof and the

lot upon which it is situated, shall be kept in good repair. .. [and

that] [t]he owner shall be responsible for compliance with the

provisions of this section," Multiple Dwelling Law § 4(4) defines a

"dwelling" as "any building or structure or portion thereof which is

occupied in whole or in part as the home, residence or sleeping place of

one or more human beings." Thus, while it is true that the duty imposed

by MDL § 78 (1) is non-delegable (Mas v Two Bridges Assoc. by Nat. Kinney Corp., 75 NY2d 680, 687 [1990]), by the express language of the statute, it does not apply to commercial tenancies(Ortiz v CEMD El. Corp., 123 AD3d 463, 464

[1st Dept 2014] ["Multiple Dwelling Law § 78 is inapplicable because

the building at issue is not a multiple dwelling but a commercial

building."]).

For the same reasons, the New York City Administrative Code does not

impose a duty upon defendants to keep a commercial premises such as

Store #7DE in good repair. While pursuant to the New York City

Administrative Code, "[t]he owner of a multiple dwelling shall keep the

premises in good repair" (New York City, NY, Code § 27-2005[a]), NY,

Code § 27-2004[a][3] defines a dwelling as "any building or structure or

portion thereof which is occupied in whole or in part as the home,

residence or sleeping place of one or more human beings."

Nothing submitted by plaintiff in opposition raises an issue of fact sufficient to preclude summary judgment. It is hereby

ORDERED that the complaint be dismissed with prejudice. It is further

ORDERED that defendants serve a copy of this Order with Notice of Entry upon plaintiff within thirty days (30) hereof.

This constitutes this Court's decision and Order.

[1]

In light of Weissman's affidavit, which establishes the authenticity

of the lease and rider, they are before the Court in admissible form. To

be sure, leases are nothing more than contracts (Tantleff at 244). A contract "has independent legal significance and need only be authenticated to be admissible" (Brand Med. Supply, Inc. v Infinity Ins. Co., 51 Misc 3d 145(A) [App Term 2016]; All Borough Group Med. Supply, Inc. v GEICO Ins. Co., 43 Misc 3d 27, 28 [App Term 2013]; see, Fairlane Fin. Corp. v Greater Metro Agency, Inc., 109 AD3d 868, 870

[2d Dept 2013] ["A private document offered to prove the existence of a

valid contract cannot be admitted into evidence unless its authenticity

and genuineness are first properly established."]; NYCTL 1998-2 Tr. v Santiago, 30 AD3d 572, 573 [2d Dept 2006]).

[2]

The complaint concedes that the lease and rider in question binds

defendants insofar as the instant premises changed ownership after the

foregoing documents were executed."